How Pope Francis will be remembered

Tributes are flowing for Pope Francis across the world after the head of the Catholic Church has died in Rome. He will be remembered for his progressive moments that changed the world.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Not long ago, Pope Francis, like so many public figures, released an autobiography. “Hope” told the story of a leader who set many firsts.

Francis was the first pope to claim a nightclub bouncer job in his youth, which he used to “guide the disillusioned to the church”.

He was the pope who cast off the papal red shoes; the pope who clashed with an American vice-president about that country’s immigration policy; the pope who talked up the virtues of therapy; and the pope who framed climate change as an existential crisis.

He brokered peace deals, or at least the official history said he did. He expressed grief about needless death in Gaza and Russian belligerence in Ukraine.

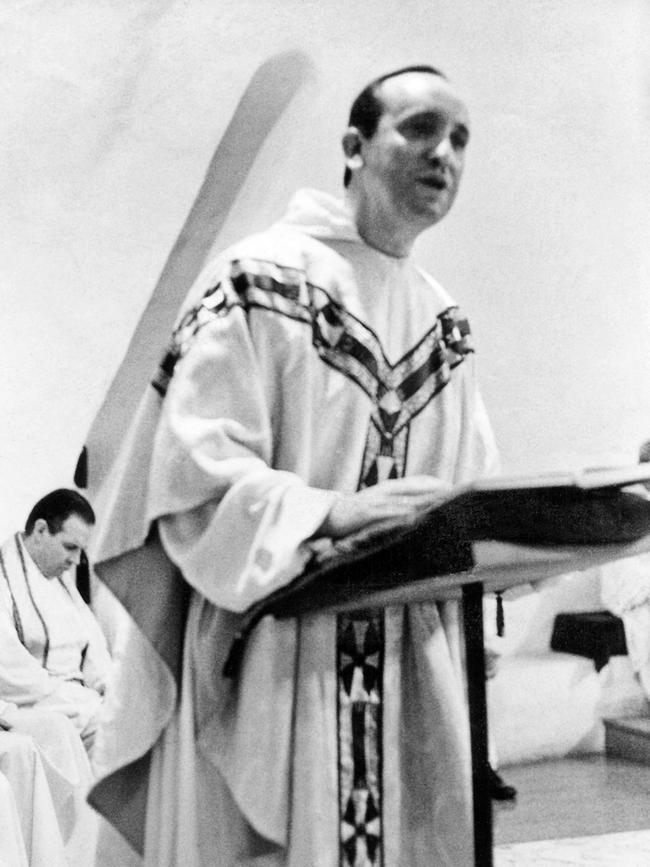

Even in his final days, Francis was working, fronting an Easter Sunday mass in Vatican City.

Francis’ memory will be bathed in the buzzwords heaped on every departing pope. Fables will bond with facts. Nods to compassion will be there, along with unity, and praise for his (liberal) reforms.

Armed with a default desire to smile, Francis cast a lightness that defied previous popes. He offered cut through messaging that did not drown in abstractions. Francis was certainly more accessible, if not quite the everyday soccer fan who liked pizza, as some of his eulogisers have suggested.

He never shied from lending the hat of a scientist or geopolitical umpire, in bursts that could be mistaken for activism. Pollution concerned him, as did unemployment. He singled out poverty and refugees for particular attention, and he fretted that Earth was “looking more and more like an immense pile of filth”.

Francis eschewed the pomp and privilege customary to his role, preferring old shoes and small cars.

He projected humility, and occasional impatience, with his hardest task – to nudge an ancient institution from its moorings in the last millennium and shepherd it into the next.

Legacies mattered to him. His book was originally intended to be published after he died, a tangible keepsake of his vision. He hoped to steer the future from the grave; 110 of the 140 cardinals who will choose his replacement are his appointments.

Among the most recent was Father Timothy Radcliffe, whose compassion for gay and LGBTQ Catholics has been lashed by conservative Catholics as “dangerous propaganda”.

Radcliffe’s hierarchical ascent typified Francis’ approach, which has been likened to shock therapy. Typically, within the Church, his actions were followed by – as the law of physics dictate – equal and opposite reactions.

Conservative elements of the Vatican never warmed to Francis’ liberal ideas. In his book, Francis called it “backward-ism”.

His tilts into western world political narratives would never satisfy the opposing ends of church debate. He moved the dialogue beyond the Catholic Church’s pet evils, such as contraception.

Yet his “progressive” values are a relative measure.

After all, Francis thought gender ideology was “ugly”. Surrogacy was “deplorable”.

He promoted a greater role for women in the church, but rejected women as priests, despite arguing that women are “equal” to men.

He described abortion as “homicide”, but had softened in the church’s traditional view of adultery as a grave sin.

He rejected laws which criminalised homosexuality, and decreed that Catholic priests could bless a same-sex union.

“If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” he said at his first news gathering as pope.

Yet acting on a same-sex attraction would remain a sin to Pope Francis. He always opposed gay marriage.

“I have been summoned to a battle,” he said in Hope. “These years of my papacy have been a life of tension . . . but old age is always a time of grace and even of growth.’

Australia’s Cardinal George Pell, who died in 2023, embodied the resistance from within. For him, Francis was the wrong kind of pope.

The synodal process, in which leaders meet to ponder weighty issues, had grown to be a “toxic nightmare”, Pell wrote in passages published after his death.

He railed against the “attack on traditional morals and the insertion into the dialogue of neo-Marxist jargon about exclusion, alienation, identity, marginalisation, the voiceless, LGBTQ as well as the displacement of Christian notions of forgiveness, sin, sacrifice, healing, redemption.”

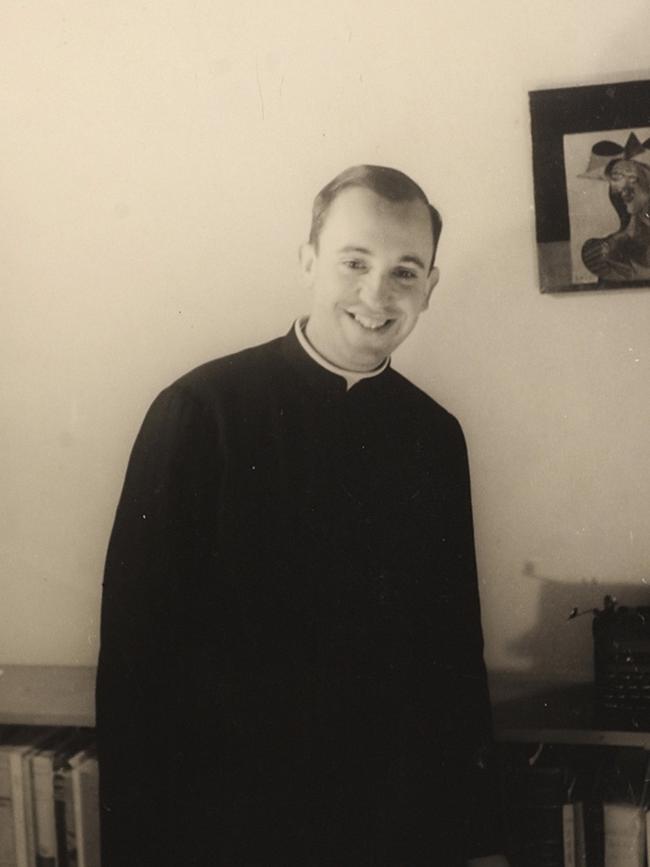

Francis cast himself as an outsider on assuming the role in 2013. Jorge Mario Bergoglio – or Jorge who? as some called him at the time – wanted to be known as Pope Francis after the saint who chose poverty.

Francis’ family’s migration to South America, as third-class ticket ship passengers and as political migrants of Mussolini’s Italy, informed his lifelong advocacy for those fleeing oppression.

He tackled many social issues. Consumerism was a cancer and a plague. “The delirium of an unbridled, blind and rampant materialism” caused world hunger, not the birth of too many children.

Francis lobbied the western world to provide vaccines for poorer parts during Covid. He feared the prospect of future conflict, which was “beginning in hearts”, citing intolerance and nationalism, in what may be remembered as one of his wisest reflections.

He suffered “melancholic spells” from the age of 10. At 21, part of a lung was removed when a bout of pleurisy almost ended his life.

The oldest of five, and highly educated, his mother had wanted him to be a doctor. He was a happy kid, “mischievous” by his own measure, and committed “sins” of which he felt ashamed.

He dated his church awakening to 1953, when at 16, on a whim, he took confession on Argentina’s Student Day, which is celebrated with a big party.

“I don’t know what happened, I don’t remember,” he later said. “I don’t know why the priest was there, whom I didn’t know, why I had felt that desire to go to confession, but the truth is that Someone was waiting for me.”

Francis loved dancing, especially the tango, as a teenager, and spoke of his attraction for at least two women in his youth.

He relished poetry and opera, as well as movies, though his decision in 1990 to no longer watch television – “God was asking me to do it” - thwarted his live barracking for Argentina’s San Lorenzo football club.

He joined the Jesuits in 1958, where he studied philosophy and psychology, and became a priest in 1969.

During these early days, he lamented the poverty of Buenos Aires’ shantytowns. In 2013, now a figure of global scrutiny, his role in events almost 40 years earlier in Argentina would be questioned.

Under a military junta, perhaps 30,000 citizens “disappeared” in Argentina. At the time, Francis was a regional leader of the Jesuits, and two priests in his care were imprisoned and tortured. One of them, Father Orlando Yorio, felt betrayed by Bergoglio.

Adolfo Perez Esquivel, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his human rights advocacy, later said that he doubted that Francis was complicit in the dictatorship, but thought that he “lacked the courage to join our struggle for human rights in the most difficult moments”.

In 2013, Pope Francis was presented with a large white box by his predecessor. It contained scandals which confronted the Catholic Church - presumably only a sample of the scandals, given written records of all of them would fill many, many large boxes.

Like his predecessors, Francis appeared more likely to speak against the sex abuse failings of his Church than act against them. “Victims must know that the Pope is on their side,” he wrote. Yet his deeds, or lack of them, were not always perceived to match the rhetoric.

Francis’ worst PR moment was a visit to Chile in 2018. He had appointed a local bishop who stood accused of covering up the sins of a pedophile priest. Francis accused sex abuse victims of slandering the bishop. He lost the crowd.

Francis reassessed his outburst. He defrocked the priest, and said: “I would learn over the following months the full extent of the many abuses in the diocese of Osorno.” His awakening was too late: a 2018 poll found that 46 per cent of Chileans identified as Catholic, down from 63 per cent a year earlier.

That same year, an archbishop and former Vatican ambassador to the United States said that he had five years earlier told Francis about claims of sexual abuse by a former archbishop of

Washington (who eventually resigned). The pope had not explored the claims, he said.

A biographer, Paul Vallely, said Francis had been “ambivalent” and “muddled” by sex abuse in the church. It was “never at the top of his priority list”.

A former editor of the Catholic Herald, Peter Stanford, said: “To understate his own errors as part of Catholicism’s colossal failure to protect children in its care from sexual abuse by priests weakens the power of his message…”

Perhaps Pope Francis did not succeed in changing the perception of a church more engaged in protecting itself than offering support to its victims.

He was the first pope from the southern hemisphere, and the first pope from the Americas.

He moved the dial on the Church’s intransigence, much as Princess Diana’s death forced the royals to grasp that once grand traditions can morph into damaging displays of coldness and detachment.

Francis was speaking of reforms to Vatican officialdom, but he could have been speaking more broadly when he wrote: “(I)t was not easy to move away from the curse of ‘it has always been done like this’ but now at last it is set on the right path.”

Yet Francis was not the first pope to convince its western world followers that the church had belatedly recognised – and repaired - its wobbles in a changing world.

That first awaits Pope Francis’ replacement.

Originally published as How Pope Francis will be remembered