The Alfred hospital’s intensive care unit is running “at or near capacity” almost every day, with doctors warning demand for beds will only rise.

Medics in Australia’s largest trauma centre have described their work as “like a battle in the dark”.

The Herald Sun witnessed the challenges first-hand this month as it was granted exclusive access to the emergency and trauma centre on a chaotic Saturday night.

At one stage, medics performed an emergency cardiac surgery on one man on the ward, who tragically died.

Following the harrowing night, doctors at the ICU – where many emergency patients end up – revealed the incredible and growing pressure they are under.

The Alfred intensive care unit deputy director Andrew Udy said demand had been steadily increasing for years and they had been running “essentially at or near capacity for quite a period of time”.

A “surge” ICU – where an additional eight to 10 beds are made available – was commissioned during Covid’s first wave to prepare for the influx of seriously ill patients.

But Professor Udy said the hospital had been forced to open the surge unit on several occasions for “business as usual” non-Covid cases, including just a few weeks ago.

“Even though the number of severe cases of Covid-19 has reduced significantly, there’s still a lot of demand for ICU,” he said. “It’s definitely more than a couple of times a year.

“There is always this tension for us – even on a daily basis – are we going to meet the demand, do we need to look at opening this space or not.”

He said intensive care was a “growth” industry and the severity of illness was rising.

“Every year there’s going to need to be an increase in ICU capacity within Victoria,” he said.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data from the past decade shows the number of severely unwell patients admitted via emergency – some of whom will be transferred to ICU – has soared.

The Alfred admitted 11,128 emergency patients and 896 resuscitation patients – the two most serious triage categories – in the most recent financial year, compared to 8560 and 765 in the 2012-13 financial year. Professor Udy said there was no one cause, with chronic illness, mental health, alcohol-related injuries, falls, road accidents and other trauma patients all needing intensive care.

“There’s a high number of (ICU) cases through the operating theatre, there’s cardiothoracic cases, transplant cases and there’s also quite a high number coming through the emergency department with major trauma.

“Over the last decade, there’s been a steady requirement for a greater number of ICU beds related to ongoing trauma.”

Professor Udy said advancements in emergency care also drove ICU demand, while he believed ICU demand would rise at a higher rate at The Alfred because they housed several specialties for critically ill patients, such as trauma and the state’s sole adult burns service.

“Our patients that come in post-heart or lung transplant or with major burns or trauma, they do receive care that is right on the edge in terms of the technology.”

The key to increasing ICU capacity was training, he said, with high numbers of specialist staff required.

“There really needs to be a focus on training an ongoing critical care workforce if we’re going to be able to meet future demand.”

The calm before the storm

In the dark of the night, you hear the helicopter before you see it.

A doctor and nurse, donned in blue gowns, wait silently as a dark shadow cuts across the lights of the city skyline.

They have been briefed – they know the man aboard, injured in a car crash, is critically ill.

He is so unwell, the team waiting downstairs will need to perform a surgery perhaps best described as ‘open CPR’.

Two Emergency Physicians and Trauma Specialists will take turns to clasp their hands around his heart and pump it for him.

But for now this is the calm before the storm.

The helicopter blades slow, the hospital’s doors slide open and the pair run out to meet their newest patient.

Welcome to a Saturday night at The Alfred, home to Australia’s largest trauma service.

Back-to-back trauma cases

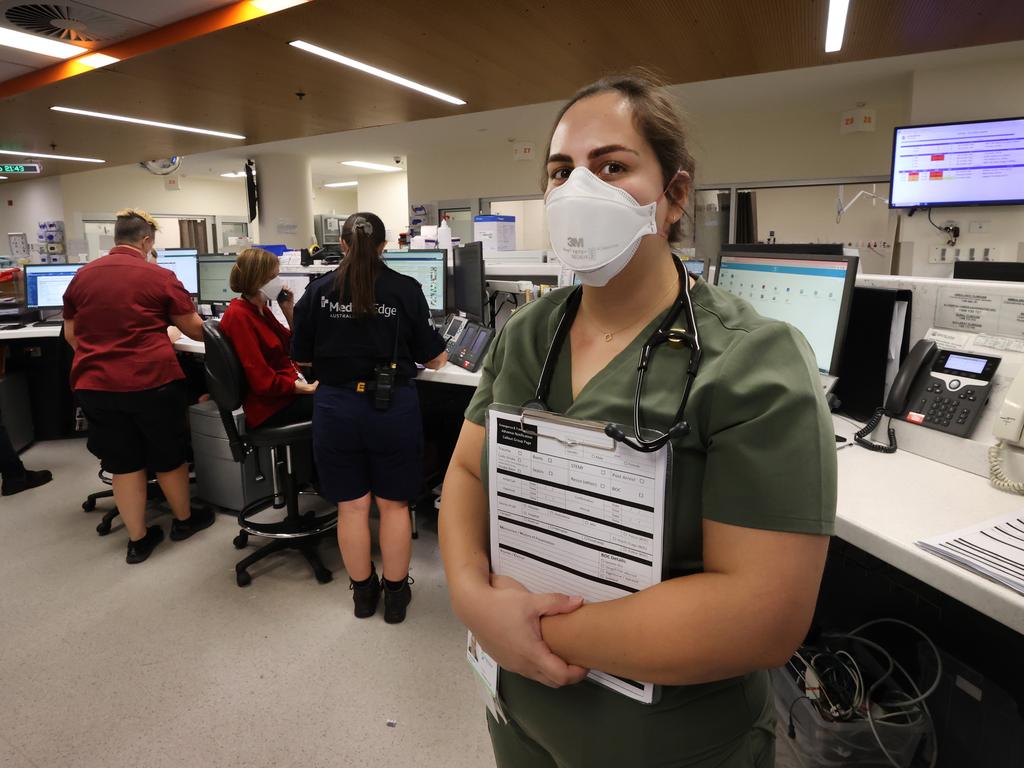

Just a few hours before the Air Ambulance touched down, Dr Alessandro Costa had said the busiest time in the Trauma Centre was “probably” between 8pm and 11pm.

The trauma doctor is working his third shift at The Alfred and says while seeing back-to-back trauma cases can sometimes “weigh you down”, he focuses on the fact that, now patients are here, he can help them.

“Working in trauma is like a battle in the dark, but we have got a lot of torches,” he says.

They will need them tonight.

It is just after 7pm and the Emergency and Trauma Centre is already busy.

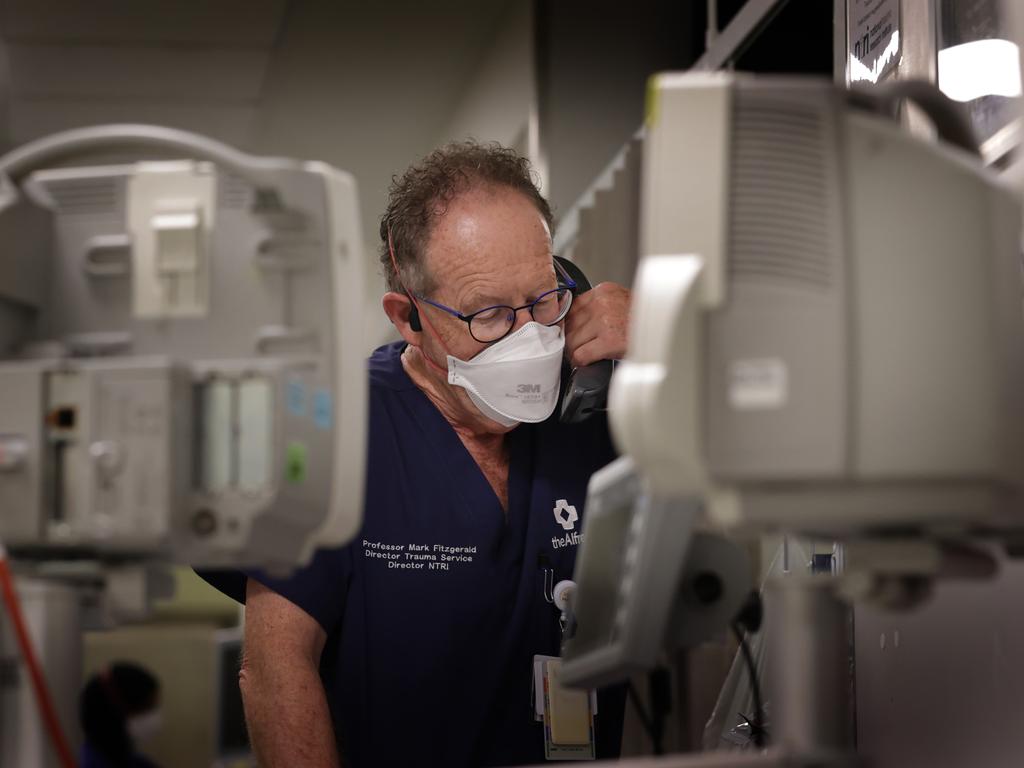

Trauma Services director Professor Mark Fitzgerald points out the different sections, from the waiting room where walks-ins are triaged to a separate mental health area, so that psychiatric patients can be treated in a calmer space than a busy emergency room.

Prof Fitzgerald spends most of his time that night in the trauma centre, a corridor of bays directly behind emergency where the most seriously injured patients – including those who need to be resuscitated – are taken.

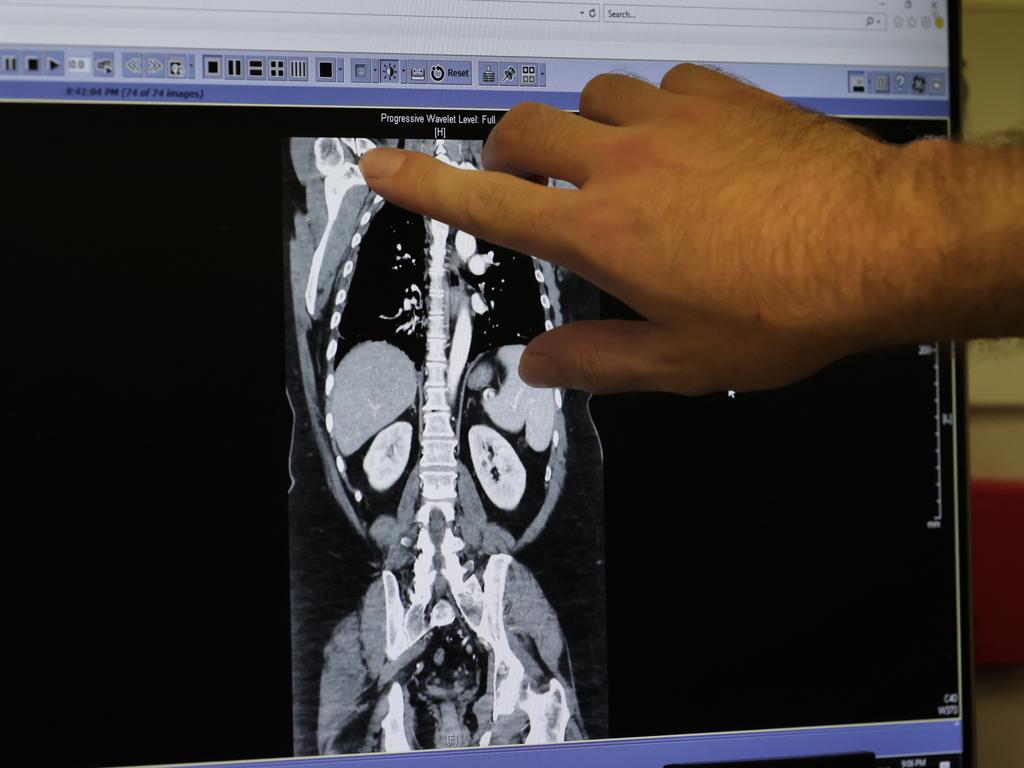

It is here the Professor studies the scans of a teenage boy, who arrived with suspected spinal injuries, followed by his shaken family.

Across from him lies another man, also in a neck brace, with a smear of blood across his face and his big toe bent at an angle no toe should ever bend.

Dr Costa says the typical trauma patient never has just one injury, and will usually require four or five different specialties to weigh in on their care.

One such patient lies in Trauma 3, with his wife Catherine Burke standing at his bedside, stroking his hand.

Craig Wallace didn’t know it at the time, but The Alfred’s staff had, in many ways, been expecting him.

Motorbike injuries are a common complaint in the hospital, with the intensive care unit alone treating 85 patients last financial year.

The trauma team tend to Craig – wheeling him off for a CT scan, checking in on his pain levels – with a calm familiarity.

A screen above his bed lists off his injuries – suspected concussion, broken collarbone (and potentially ribs).

But the scratches on a black Harley-Davidson motorbike helmet, perched on a metal trolley near his bed, hint at how much worse it could have been.

He was just a few streets from his Carnegie home, when his bike seized beneath him as he turned off a main road.

Catherine says she didn’t expect to spend her Saturday night here – it was his first time riding in a while – but Craig remains cheerful.

“I feel OK, I’m just scared to move,” he says.

“Everyone here in the hospital has been really good.”

It’s only been a few hours since his accident – staff are yet to remove his neck brace – but he is open to getting back on his bike.

He says a similar accident more than a decade ago, but on his skis, couldn’t keep him away from the snow so “you never know”.

His wife jokes that she will trade in his bike for a truck.

‘Typical Saturday night’

By 9.30pm, the pace has picked up.

In the Trauma Centre, there is a steady turnover of patients. In the cubicle once home to the teenager with suspected spinal injuries, there now lies another young man.

A bandage – stained red – is taped to his eye and he curls into his side as he moans in pain.

Around the corner, Emergency physician Panagiota Kakridas stands in front of the ‘flight deck’, where a team of people from the nurse in charge – “the most important person in the room” – to an ambulance liaison officer manage the never-ending stream of people.

Dr Kakridas says it’s a “typical Saturday night” with a “lot of young people”.

Tonight, her patients will include two people burned in a barbecue explosion — which she says is “typical for summer” – road accident victims, several intra-hospital transfers and an air ambulance patient picked up 300km away in regional Victoria.

There is also an international medical transfer from a country in East Asia, and “a lot of young people … very drowsy and sedated after alcohol”.

“That’s a big problem with our workload,” she says.

She estimates drug and alcohol-affected patients make up to 30 per cent of their cases on a Friday and Saturday night.

She says she has seen an increase in emergency patients over her 10 years at The Alfred, especially among elderly patients seriously injured in falls and, more recently, e-scooter victims.

“We definitely didn’t use to get that,” she says.

Careful choreography to the chaos

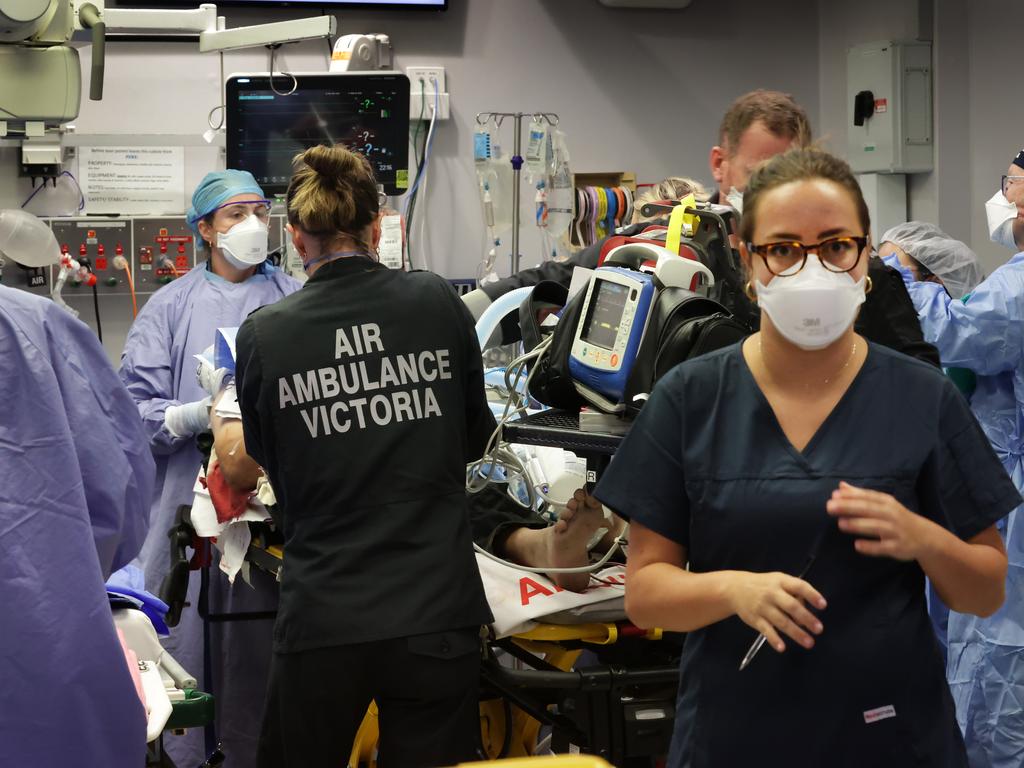

It’s 10.30pm and the Trauma Centre pulses with a life of it own.

The constant beeping, the frantic footsteps, the nurse ferrying countless blood bags as doctors call for more, the sounds of other patients – unaware of the desperate efforts to save a man just metres away – the streaks of blood on the floor.

It should be mayhem.

But there is a careful choreography to the chaos unfolding in Trauma 4, as staff retrace the steps of earlier rehearsals.

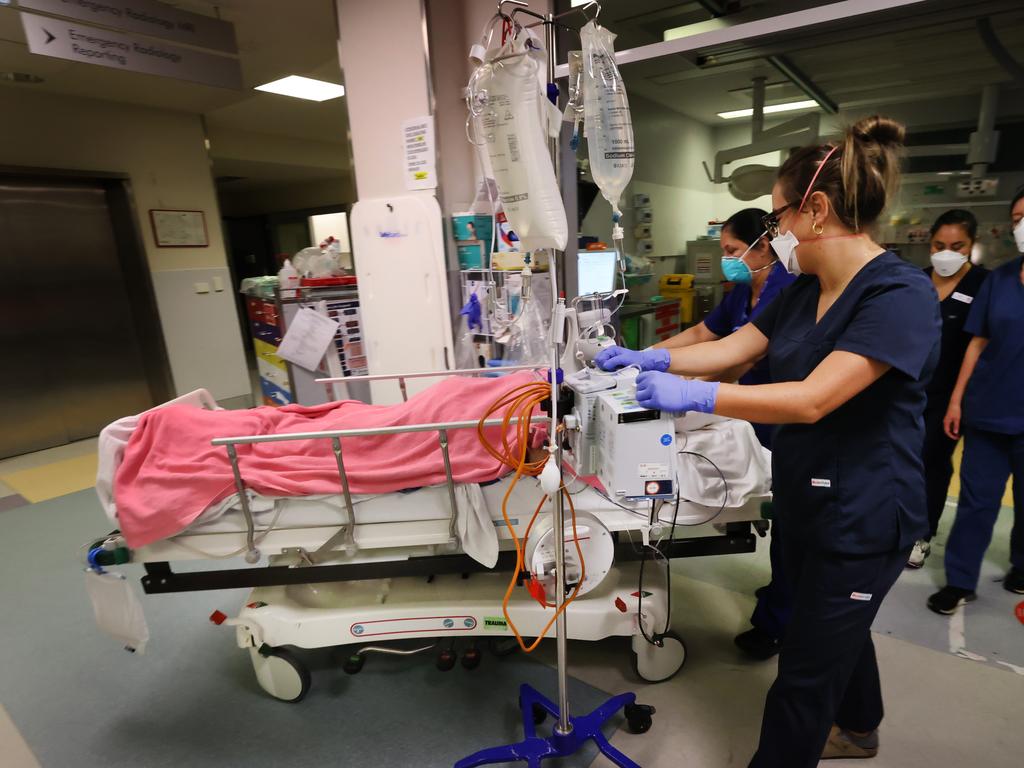

When news of the man’s flight – the second that night – breaks just before 10pm a wave of nurses, trauma doctors, surgeons, anaesthetists and cardiologists arrive.

They form a sea of blue in their gowns and masks as they scrub in, a senior doctor running through everyone’s tasks down to who will stand of which side.

In the patient bay opposite, four more staff, from the operating theatre team upstairs, check trays of shiny, silver surgical tools.

They are ready for their patient.

When he is wheeled out of the elevator at 10.15pm, everything happens at once.

Within minutes they make their first cut – small incisions on both sides of the chest to drain any trapped blood or air.

When it becomes clear the man’s heart has no blood to beat, they expose more of his chest – and struggling heart.

Two Trauma Specialists take turns to place their palms around it. His heart, his very life, is in their hands.

Prof Fitzgerald says this technique is called “open cardiac massage”, and aims to restore the patient’s circulation when traditional closed CPR would be futile.

At times, it’s silent as the team stills while two specialists perform a particularly delicate task.

At others there is a moment of hope, prompting the team of up to 20 people to try for another half an hour to save the stranger before them.

And then, the reality shifts, and two senior doctors exchange a knowing glance after blood test results are read aloud.

After about an hour, their movements slow and the room begins to empty.

A silence falls, a curtain is drawn and colleagues help each other out of their bloody gowns.

After careful discussion between several senior doctors, the team makes the call. The man cannot be saved.

Prof Fitzgerald emerges from the room. He knows the odds were slim, but for a moment the team had hope. He is disappointed.

“I thought we had him for a minute,” he says.

“We thought we had it.”

Prof Fitzgerald later says for cases like this, survival rates can be as low as 7 per cent.

‘It’s the worst day of their lives’

Behind the curtain, a smaller team remains.

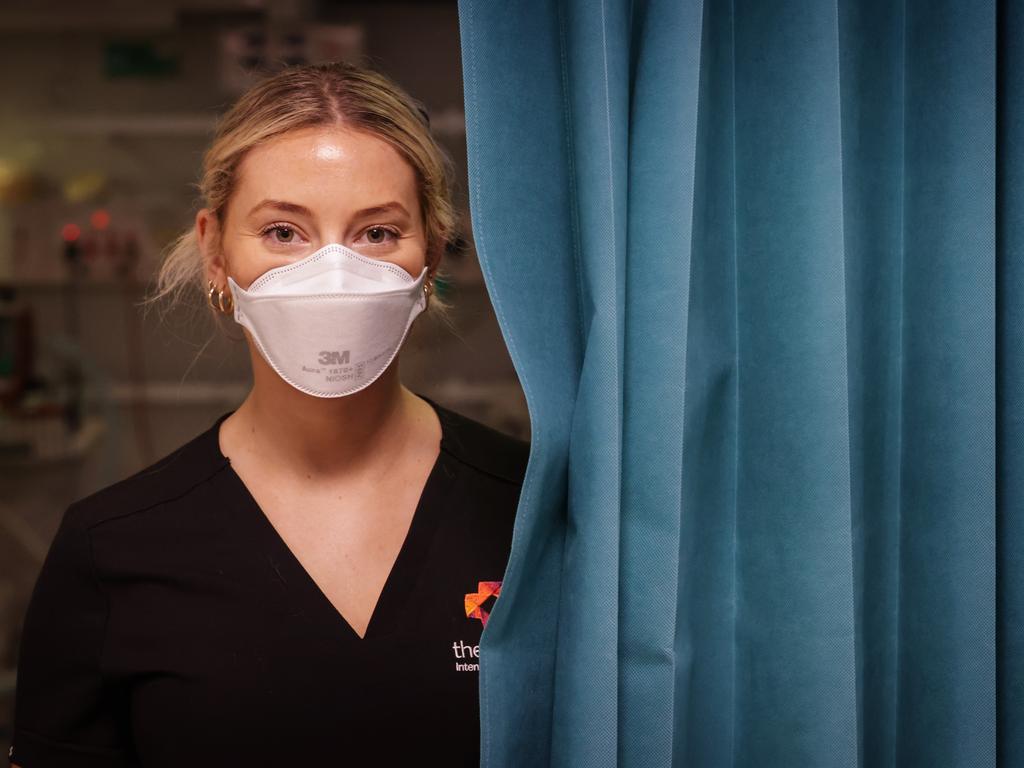

The public associates medicine with life, but emergency nurse Christina Fritz says it is also a privilege to care for people at the end, and ensure they are treated with dignity.

“It’s a huge privilege to look after people because it’s the worst day of their lives,” she says.

Critical nurse Lizzie Peters says staff try to leave the losses at work when they leave, but sometimes patients will stay with them.

“There’s definitely some things that hit you closer,” she says.

But in hospital, as one life comes to an end, others must go on.

A nurse, who somehow manages to convey a smile despite the mask, is already chatting to her next patient.

A distressed young woman appears in the trauma centre, wide-eyed as she tracks the security guard and team of calm but firm nurses who lead her back to emergency.

In the corridor, a confused patient looks around the room as the paramedic pushing their stretcher explains they are at the hospital.

Prof Fitzgerald pauses, and reflects on the work they do.

He says emergency and trauma patients are like “waves” on a beach, “they never stop”.

“It is life’s gift to be able to work in such demanding and rewarding circumstances.”

‘We were still quite hopeful’

If this were a work of fiction, the man would have been saved.

But in medicine the brutal truth is not every story gets a happy ending.

How does the team continue to show up day after day to save someone, while knowing fate may have already decided they are lost?

The answer is in those they save.

The miracle tales of the 7 per cent go hand-in-hand with the losses.

In the words of Dr Faith Tan, they have to believe every trauma patient who comes through their doors – even with the odds stacked against them – will be the lucky one.

“We were still quite hopeful, but unfortunately usually when they need that kind of intervention, open CPR, statistically, we all know it’s quite grim,” she says.

“We have to do lots of them to save that one.

“You’ve got to assume that one today is that one.”

And, she says, when they do save that one, it’s going to be worth it”.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Premier’s $513,000 pay day as politicians score salary boost

Jacinta Allan has cemented her status as the nation’s highest-paid premier while the base salary for Victorian backbench MPs has jumped to $212,000.

‘Fight night’: Cornes to face off with clubs who banned him

Polarising commentator Kane Cornes says he won’t shy away from his on-air role as he prepares to come face-to-face with the two teams who have banned him on Thursday night.

E-bike rider faces court over crash that killed pedestrian

An e-bike rider who allegedly hit and killed a pedestrian in Hastings while drug-affected has appeared in court for the first time, nursing a broken arm and keeping his head in his hand.

‘Common sense approach’: Allan defends Voice plan

Jacinta Allan has hit back at critics of her government’s plan to establish its own Voice to parliament, claiming the move was not about “changing the constitution” and would result in better outcomes for all Victorians.

Two police officers allegedly mowed down by stolen ute

Two officers have been injured after a ute allegedly reversed “at speed” toward them in wild scenes at a Ballarat car wash, with one of the suspects still on the run.

Privacy screens appear at Erin Patterson’s Leongatha home

As the jury retires to deliberate, privacy screening has appeared at Erin Patterson’s Leongatha home, shielding it from prying eyes.