Monash University team show how smoking inhibits protective lung protein

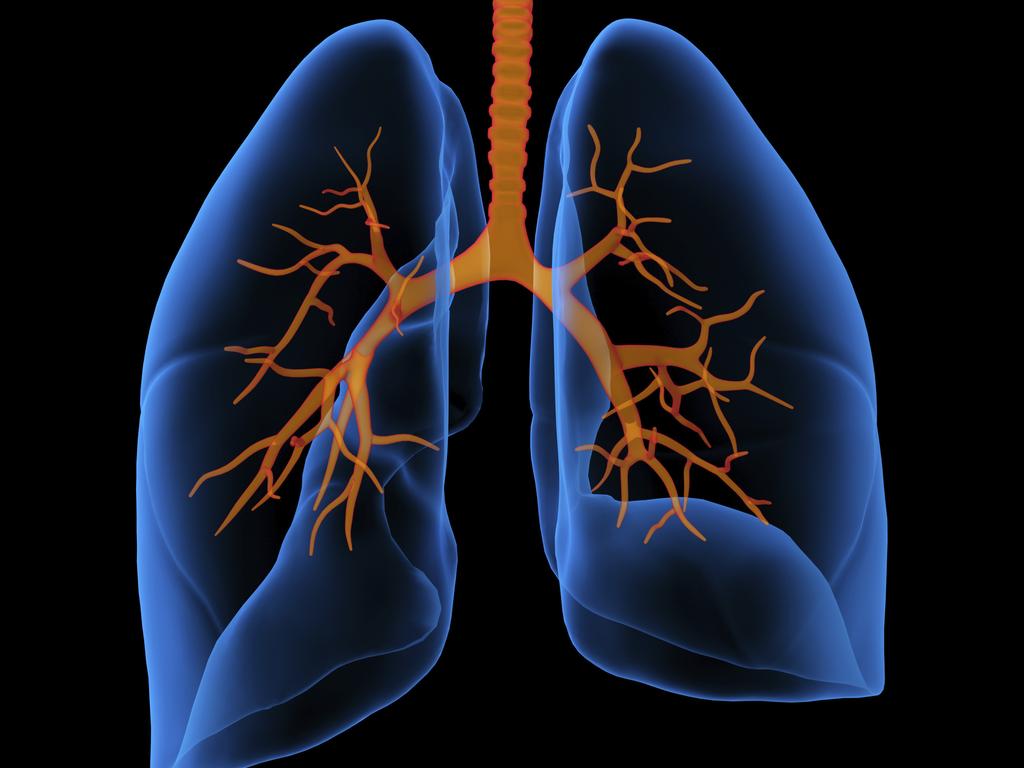

For the first time, Australian researchers have revealed how exposure to smoking may cause a deadly lung disease, harming protective proteins meant to ward off infection and cancer.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For the first time Australian researchers have identified how exposure to smoking may cause a deadly lung disease that claims thousands of lives every year.

In new research published on Saturday researchers revealed how smoking inhibits the function of protective immune cells in the lung. They say it gives a greater understanding of the mechanisms underpinning chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Following almost a decade of research, the Monash-led team hopes the discovery can eventually lead to an effective treatment for COPD.

This is a severe obstruction of the lungs that interferes with normal breathing. More than 630,000 Australians live the disease that is mainly caused by smoking, but exposure to bushfires and other environmental factors may also contribute.

The team from Monash University’s Biomedical Discovery Institute with collaborators from across Australia showed how thousands of chemicals in cigarette smoke and e-cigarettes alter the function of a type of immune cell in the lungs activated by a protein called MR1.

MR1 are found in almost every cell of the body and recognise chemicals produced by bacteria. They then initiate an immune response to protect the body from infection.

The Institute’s Dr Wael Awad Abdelhady is the first author of the study that was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“When people smoke, they inhale what is called primary smoke,” Dr Awad said.

“And then people around the smoker, including children, might smell smoke. That’s called second-hand smoke. Then if you ride in a car with a smoker you may smell smoke on surfaces and this is third-hand smoke.

“It was very interesting to find that even people who are not smokers, but live in a family with smokers, are being impacted by the harmful impact of components of third hand smoke.”

He described MR1 as being like a molecular alarm system to detect infection or cancer.

Dr Awad said smoking impacts MR1 functions, which in turn stops the immune system doing its job to protect the lungs.

“We know smoking is very dangerous and it’s the third leading cause of death worldwide,” he said. “It compromises immunity and drives many smoke-related disease.”

Dr Awad said COPD was one of the most common respiratory diseases related to smoke, but the mechanism of how cigarette smoke initiated the disease was unknown, until now.

“The mechanisms underlying the skewed immune responses in people exposed to cigarette smoke, and how they are related to smoke-associated diseases like COPD, was unclear,” Dr Awad said.

“The main issue is that we don’t have any treatment for COPD because we haven’t understood the disease.”

The team found in preclinical studies on mice that MR1 binds to many compounds in chemicals found in cigarette smoke. It also binds to those used to flavour e-cigarettes.

“All of these compounds bind to MR1 and inhibit a function in the lung that stops our body being able to protect itself against influenza and bacterial infection. After years of this inflammation of the lung, COPD develops,” Dr Awad said.

Professor Jamie Rossjohn from the Institute co-led the study with Professor David Fairlie of the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at University of Queensland, University of Melbourne Professor Alexandra Corbett at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, and Professor Philip Hansbro of the Centenary Institute and University of Technology Sydney.

The researchers plan to investigate which cell pathways are impacted by cigarette smoke to learn how to better treat COPD and other lung diseases.

Originally published as Monash University team show how smoking inhibits protective lung protein