Andrew Rule: New book uncovers fact from fiction in Mafia’s past

Al Capone didn’t wake up one day with a machine gun and barrels full of prohibition whisky. So where does the story of the Mafia begin?

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There’s nothing like the prospect of sudden death to concentrate the mind. That thought struck the undercover cop as he watched the Australian coast vanish below the aircraft he was sharing with three heavies who would throw him from a great height if they suspected he was an informer.

He recalls it this way: “I was in the back seat of a rented Piper Navajo Chieftain … It flew like a bullet, and I knew there were a few real ones on board. Some of them were inside my tiny .32 calibre pistol, stashed away among the foam innards of the seat, just in case I needed to reach for the weapon quick. I guessed there were another three weapons nearby.

“I’d left my home town of Melbourne three sleeps back to get this far: nowhere. We call it the never-never, which means you should never go there as you may never come back; it’s where the mafia grow their massive cannabis crops, undetected.”

It’s a hard-boiled start to a hard-edged story that former detective Colin McLaren has told in various forms for the good reason that he’s entitled to.

That secret trip to a Torres Strait island in 1994, ready to bring back a huge payload of “skunk weed”, ended in mass arrests. For McLaren, it was the climax of two years of constant danger inside the Australian branch of the Mafia.

The bad guys were the Calabrian ’Ndrangheta, responsible for murdering Donald Mackay in Griffith in 1977 along the way to running vast drug rackets across Australia and the world.

McLaren was posing as Cole Goodwin, a bent art dealer promising to invest the mob’s dirty money

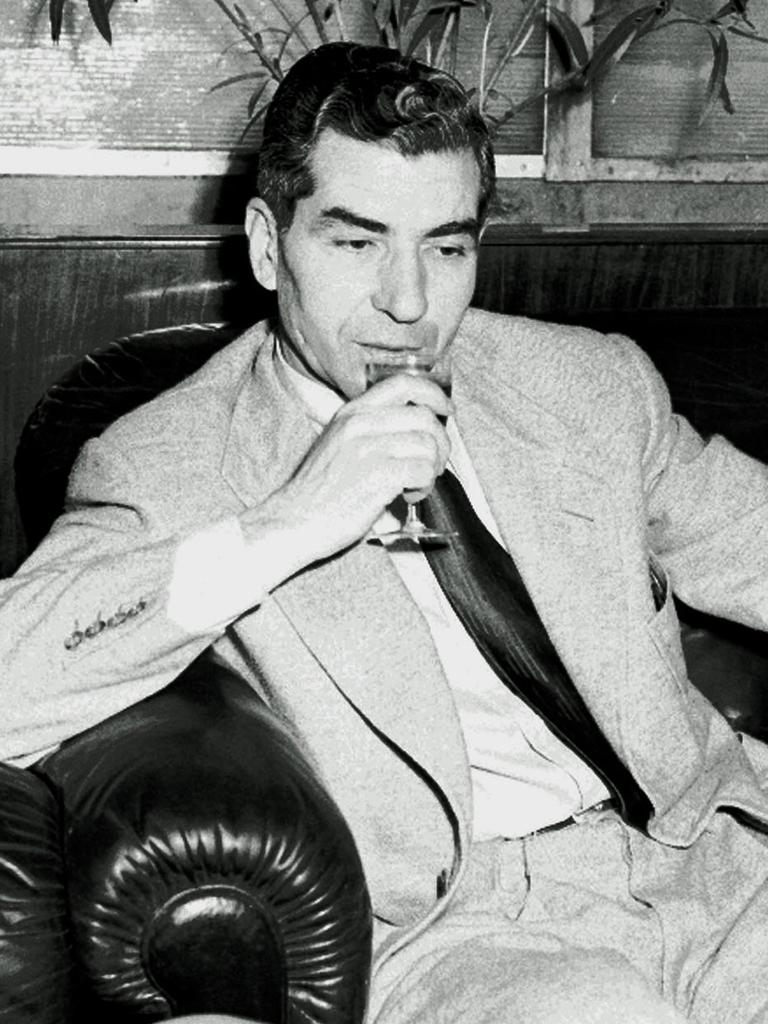

In fact, he was gathering evidence against big mafia players. One of them, the dashing Tony Romeo, paid for his mistake with his life, via a sniper in a Griffith orchard after his release.

McLaren quit the force and spent years looking over his shoulder. He turned to writing, applying detective skills to tasks from reinvestigating Princess Diana’s death to the riddle of the JFK assassination, crafting a credible addition to the slew of books — conspiracy theories from the plausible to the laughable — on what happened in Dallas.

But no matter how much he distanced and distracted himself from his dangerous past, he could not bury memories of the Mafiosi families he had befriended. His experiences fired his curiosity.

What made them tick? What was their real origin?

He read a load of Mafia books but never found anything that unravelled the myths and speculation about how the crime families had begun.

As McLaren said from Rome this week, most “studies” of the Mafia have come since World War II, leaving a gap in its history for a century before that.

Since the 1970s, the entire subject had been “Americanised” by the “Godfather effect” of Mario Puzo’s bestseller and its spinoff films.

“But where’s the real history?” McLaren asks.

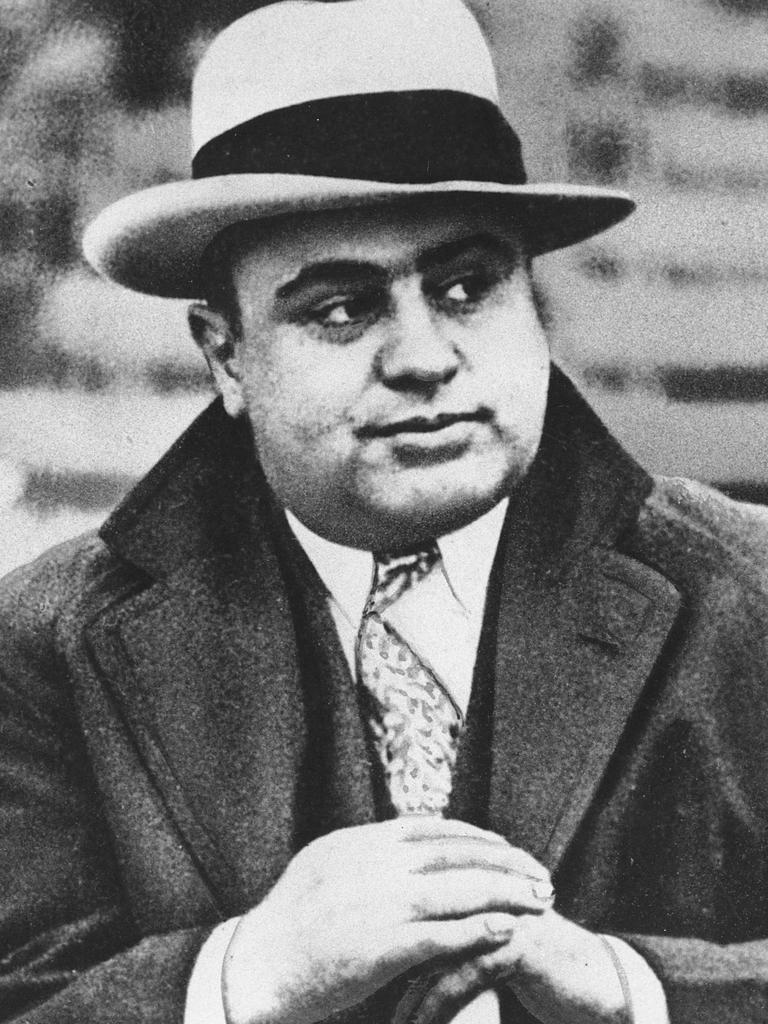

“Al Capone didn’t just wake up one day with a machine gun and a speakeasy full of prohibition whisky.”

He became a different sort of sleuth, searching archives in Italy, where records have gathered dust for close to two centuries.

Four years later, McLaren has emerged with his latest book, Mafioso, which he says casts light on the relatively obscure origins of what a Sicilian magistrate referred to in 1838 as a “sect” that ran on corruption and extortion but which by 1863 was starting to be referred to as “mafia”.

The most likely origin of the word now used as shorthand for organised crime is that it comes from the Arabic word “Mo’afiah”, meaning arrogant in behaviour and attitude.

With the help of Italian librarians, historians and translators — and a few cagey old Sicilians sharing family stories — he has pulled together a narrative of how tough mountain men described by contemporary police as brigands, “assisted” the legendary Giuseppe

Garibaldi and his “thousand” volunteers to topple the Bourbon regime in Sicily and Calabria to unify Italy.

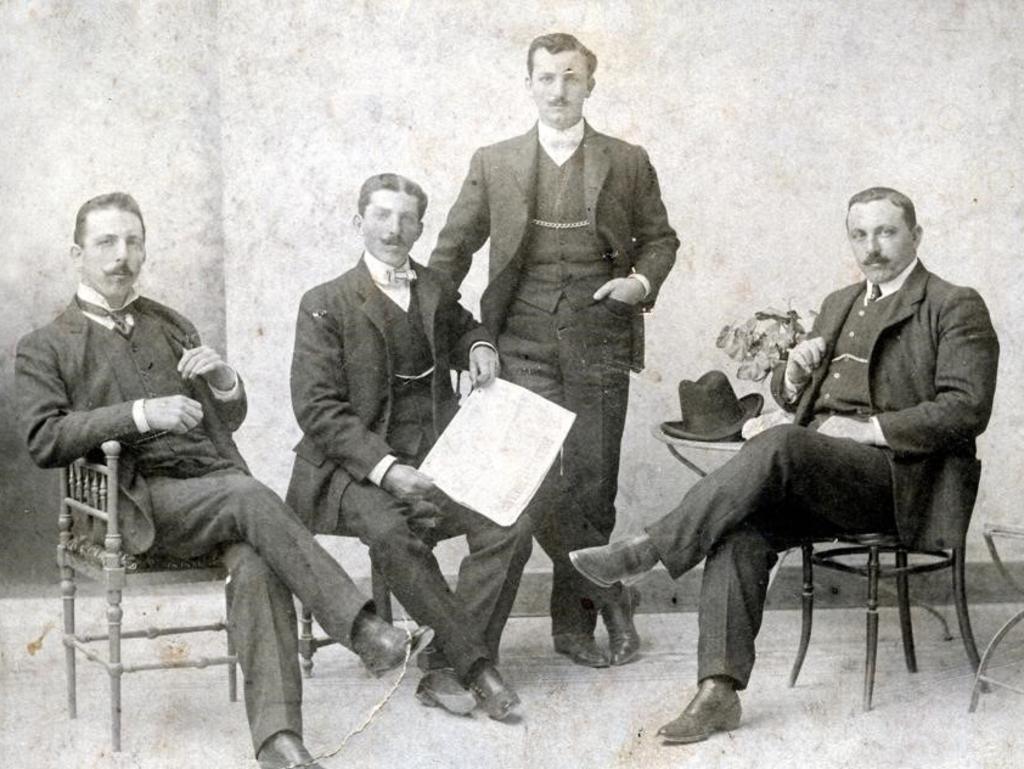

Well before Garibaldi arrived in Sicily in 1860, bandits known as “picciotti” (translated as “young men with attitude”) infested the countryside. Landholders hired some as vigilantes against rival gangs, and these guns-for-hire colluded to set up systematic extortion, corruption and robbery, a forerunner of the modern mafia’s global crime networks.

The legend that Garibaldi conquered “the two Sicilies” with 1000 volunteers doesn’t hold water, McLaren says. The reality, he argues, is that Garibaldi recruited local hard men ranging from hungry peasant farmers to criminals, mercenary guerrillas attracted by the chance to loot — and the promise of land confiscated from local landlords.

But Rome’s overwhelming failure to deliver on the promise of land, he says, turned many desperados into murderous mobs with a grievance.

In one riot, a notary was torn apart and burnt, his heart and liver cut out and eaten in front of the crazed mob. Savage police reprisals over the “broken promise” riots welded the guerrilla bands into ruthless organised groups who distrusted any form of justice except their own rule by knife, gun and bomb.

By 1863 Palermo’s biggest prison was being run by a feared network of inmates. By 1900, the three inescapable things in Sicily were death, taxes and the mafia — the same with the Camorra in Naples and Calabria’s ’Ndrangheta.

New, fast ocean liners and mass migration syphoned people from the mean mountain villages. The mafia was exported to the Americas as efficiently as their citrus crops — both through legitimate migration and people-smuggling on ships transporting oranges and lemons.

Most departing Sicilians went to New York, sowing the seed that produced Lucky Luciano, Frank Costello, Al Capone and eventually the “five families” that would lead to the “Godfather” franchise that is now part of popular culture.

But McLaren dismisses academic theories that Hollywood “created” the mafia. The reality, he says, is that the mobsters’ own bloody history came first, then art imitated life. The fact no one recorded the mafia’s evolution during Mussolini’s fascist years between the wars didn’t mean it wasn’t happening.

Mussolini sent the Iron Prefect, Cesare Mori, to Sicily in 1924 to smash the mafia, which at that time killed hundreds of people a year and cowed the population. But Mori’s mass arrests and cruel treatment of low-level mafiosi, and poor people generally, amplified hatred and mistrust of authority, especially police. And it did little to suppress rich and powerful mafia leaders such as Don Vito Cascio Ferro.

It was Don Vito who pulled off a real-life hit that predated the Hollywood hits. It was in 1909, when a heroic Italian-American policeman, Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, was sent from New York to halt alarming numbers of Sicilian mafiosi infiltrating the US.

Petrosino found how racketeers were smuggling crooks to New York and was set to uncover it when Don Vito struck: he slipped out of a society dinner in Palermo, killed Petrosino in the street and returned to the gathering. As still happens in Sicily, nobody saw a thing.

History turns on such events. If Petrosino had survived to clip the mafia’s wings, McLaren argues, far fewer mafiosi would have reached America to work for the likes of Lucky Luciano, Al Capone and Frank Costello, racketeers who ran rampant in the Prohibition era between the wars.

But the missing link between the 19th century and the present was not Don Vito but his younger rival Ernesto Marasa, a ruthless boss who was never called “the Godfather” in his life but created the template the modern mob is built on.

By the time Marasa died in 1948 he had formally imposed the “omerta” code of silence and blood-and-fire initiation of “made men” that Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola would make part of popular culture.

He also dodged prison through corruption and secretly informing on his enemies. The very model of a modern mafioso.

MAFIOSO, by Colin McLaren. Hachette. RRP $32.99

More Coverage

Originally published as Andrew Rule: New book uncovers fact from fiction in Mafia’s past