Tasmanian Aboriginal community “not believed” over risks in out-of-home care

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre says it’s frequently “not believed” or “ignored” when raising the alarm that Indigenous children are being harmed in the state government’s out-of-home care system.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre says it’s frequently “not believed” or “ignored” when raising the alarm that Indigenous children are being harmed in the state government’s out-of-home care system.

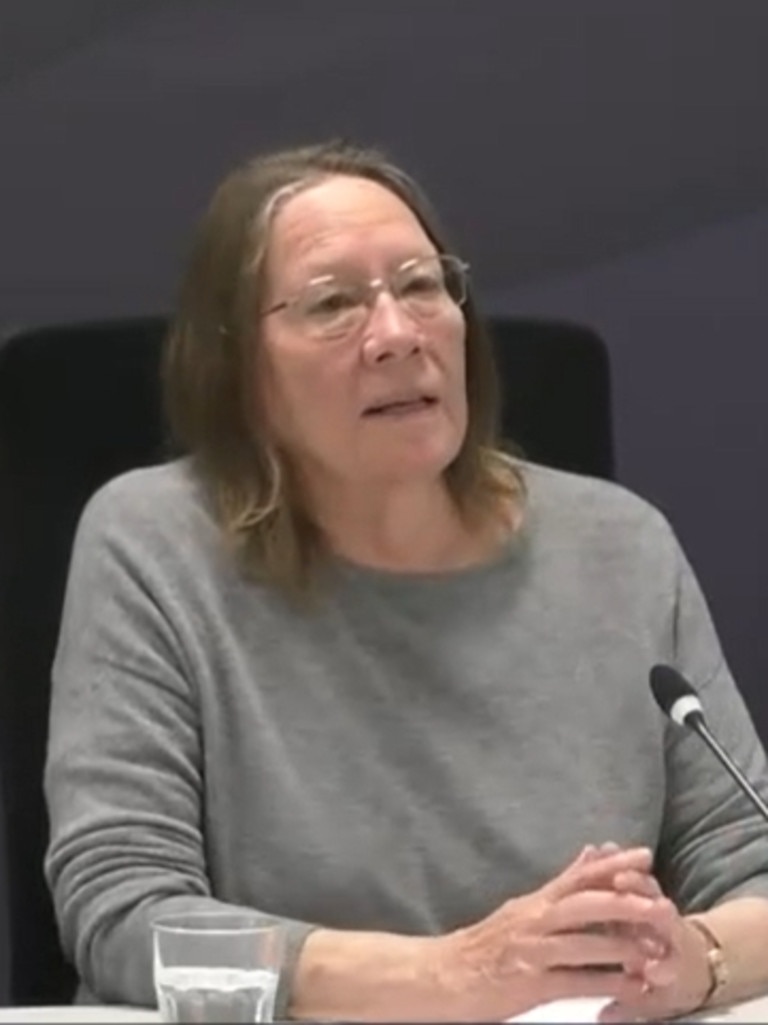

Giving evidence to the Tasmanian child abuse commission of inquiry on Wednesday, the centre’s CEO, Heather Sculthorpe, said the organisation aimed to keep Aboriginal children within their extended families, rather than becoming part of the statutory system.

“They get lost to us,” she said.

“It’s totally within the power of people in welfare to choose where the child goes.

“We’re often not believed about the bad things that are happening in care.”

Ms Sculthorpe said sometimes, Aboriginal children were being neglected or sexually abused by their carers in the state system.

“We have been ignored and there’s been nothing we could do about it. Those kids then get moved around different programs … with terrible results.”

Ms Sculthorpe said in Tasmania, Aboriginal families who previously had their children removed, “continue to have children removed down the generations”.

She said those families were “singled out”.

“It’s often the case that they have a harder time staying out of state control than other families,” she told the inquiry.

“The way to fix all this is to empower the Aboriginal people to resume its place as guardians of its own children, as determiners of our own future, rather than handing it off to people who are the descendants of the invaders – because that is still remembered and it’s felt keenly in the Aboriginal community.”

She said one of the reasons why Aboriginal children were vulnerable to sexual abuse was because they were over-represented in institutions like out-of-home care.

She said there should be a transfer of jurisdiction over child welfare for Aboriginal children from the state government to the Aboriginal community, noting some religious organisations funded to do welfare work had handed on funding to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre.

“Sometimes the lengths that the (state government) department goes to avoid Aboriginal decision-making is pretty extraordinary,” Ms Sculthorpe said,

“I think we’ve proven that we are very fit and able to do that work but there is some reluctance to fund us to do it.”

She also criticised a widely-condemned decision to send Tasmanian Aboriginal children to the Northern Territory under Allan Brahminy’s controversial, tough-love “Many Colours One Direction” program.

“I can’t imagine why someone thought that would be a good place to send Aboriginal kids from Tasmania,” she told the inquiry.

“But again, we weren’t listened to … despite our complaints, no-one listened again, because we weren’t the decision-makers. “

The Commission of Inquiry into the Tasmanian Government’s Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings is currently examining the state’s out-of-home care system.

‘Oh, is that all?’: Foster mum’s shock response to sexual abuse

WHEN Faye* and her sibling were placed in a foster home with food, warmth and stability, they didn’t want to leave.

They’d grown up during the 1990s in a large family where their parents hadn’t been able to look after them.

In her evidence read out before Tasmania’s child abuse commission of inquiry on Tuesday, Faye explained her foster parents Ruth* and Allen* had been strict – but offered the stability she needed.

“It felt nice being in a house like this after growing up so poor,” she said.

But everything changed when Ruth and Allen’s son Louis* moved back home after he was fired from his job.

Faye later learned Louis had been fired because he’d had a relationship with an underage girl.

A trio of staff members from the state government’s Children and Youth Services came to visit, asking how Faye and her sibling felt about Louis moving home.

The workers promised to visit the pair regularly – but never did.

“Both my sibling and I wanted to stay in the home,” Faye said.

“We didn’t understand the risk or implications of (Louis) moving home”

She said Louis quickly started grooming them, gaining their trust and friendship and “acting cool”.

“He would play with us, try to get close to us and kiss us,” Faye said.

“He started to come to our room and sexually abuse me before I went to sleep.”

When she told Ruth what had been happening, she said “oh is that all?”

Eventually she told Allan, who said “this has happened too many times, they must be telling the truth”.

“I believe either Ruth knew what was happening and ignored it, or was in denial,” Faye said.

Child safety workers took Faye away from the home immediately without giving her a chance to pack her things, leaving her sibling there for a time.

“I believe Children and Youth Services continued to place female children in the home,” Faye said.

She said she was “torn because of my affections for Ruth – I was missing her as a mum”, so didn’t go through with pressing charges with police.

But eventually, about a decade later, she and a number of other girls took the matter to trial.

“We lost the court case, I don’t really know why,” she said.

“I was shattered with the result.”

Faye said she felt like her abuser had been able to do whatever he wanted and get away with it.

She also said she didn’t want to simply be paid “ via the National Redress Scheme, and then just “moved on”.

“To me, it almost dismissed what has happened. I want to be part of the conversation and make change,” she said.

Faye was the first witness to give evidence during week three of hearings in the Commission of Inquiry into the Tasmanian Government’s Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings, which is currently examining the state’s out-of-home care system.

* Names change to protect identities.

If you or a loved one are struggling, further support is available:

Lifeline Australia – 13 11 14

Beyond Blue – 1300 22 46 36

More Coverage

Rural Alive and Well – 1300 4357 6283

Kids Helpline – 1800 551 800

More Coverage

Originally published as Tasmanian Aboriginal community “not believed” over risks in out-of-home care