Cherbourg youth use their voice to overcome generational trauma

Against a backdrop of colonial oppression, hopelessness and record high suicide, Cherbourg is showing how listening to Indigenous voices can lead to effective solutions in their communities. SPECIAL REPORT

Community News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Community News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An outsider taking in Cherbourg’s historical precinct might be forgiven for thinking they were viewing relics of a bygone era.

Meticulously conserved and bounded by white picket fences, the row of wooden buildings lining the northern side of well-kempt Barambah Ave were restored by the community from 2004, the centenary of the founding of the Barambah Aboriginal Settlement under segregationist legislation known to First Nations people simply as “the Act”.

Past the Ration Shed, where Indigenous inhabitants once received flour, sugar and tea in exchange for work done on the settlement, and the Superintendent’s Office, where permits controlling the movement of Indigenous inhabitants were issued, stands the Boy’s Dormitory, a potent reminder of the disruption of connections to language and culture imposed on First Nations people by the then Queensland government.

Here, as recently as the 1980s, First Nations boys were separated from their mothers and housed until the age of 13 when they would be sent out to work on the settlement.

In 2023, 39 years after ‘the Act’ was repealed and the Cherbourg Community Council recognised as the local authority, the Cherbourg Community Clock standing at the entrance to the town with the slogan “many tribes one community” is testament to a more hopeful age of self-determination and empowerment, celebrating the survival and adaptation of Indigenous culture despite decades of subjugation.

But listen to the voices of community leaders, and those of the young people in the community being lost to suicide at four times the rate of their non-Indigenous counterparts, and it is clear that legislative and bureaucratic reforms haven’t succeeded in undoing the devastating effects of colonial-era policies that continue to bear down on the people of Cherbourg.

Edwina Stewart, community services manager at Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council, has lived all her life in Cherbourg and remembers needing to obtain permits to leave the settlement to go to the Murgon Show as a young girl.

Responsible for running programs connecting Indigenous youth to culture, Ms Stewart said a lack of educational and employment pathways was a significant barrier to alleviating the sense of “hopelessness” felt by young people in Cherbourg.

The council is the biggest employer with a staff of about 100, but has limited funding to keep young trainees on permanently, and the lack of a high school in the town means children whose families don’t have the means to get them to Murgon or Kingaroy face challenges in furthering their education.

“We’ve had kids that have come in and done TAFE courses, and they could be a trainee with council for 12 months, but then there’s no money to keep them on,” Ms Stewart said.

“It’s disheartening to these kids, because they’ve got the skills but they can’t get no employment.”

Following a 2020 Covid lockdown that resurfaced traumatic memories for the older generations, Cherbourg tragically lost 10 people to suicide in 2021, mostly men and boys aged 13-40.

The Burnett region has had the highest suicide rate in Queensland.

In response, Ms Stewart implemented programs aimed at strengthening young people’s ties to Indigenous culture and Elders in the community, including through forums where youth discussed the problems they faced in the community and, most importantly, possible solutions.

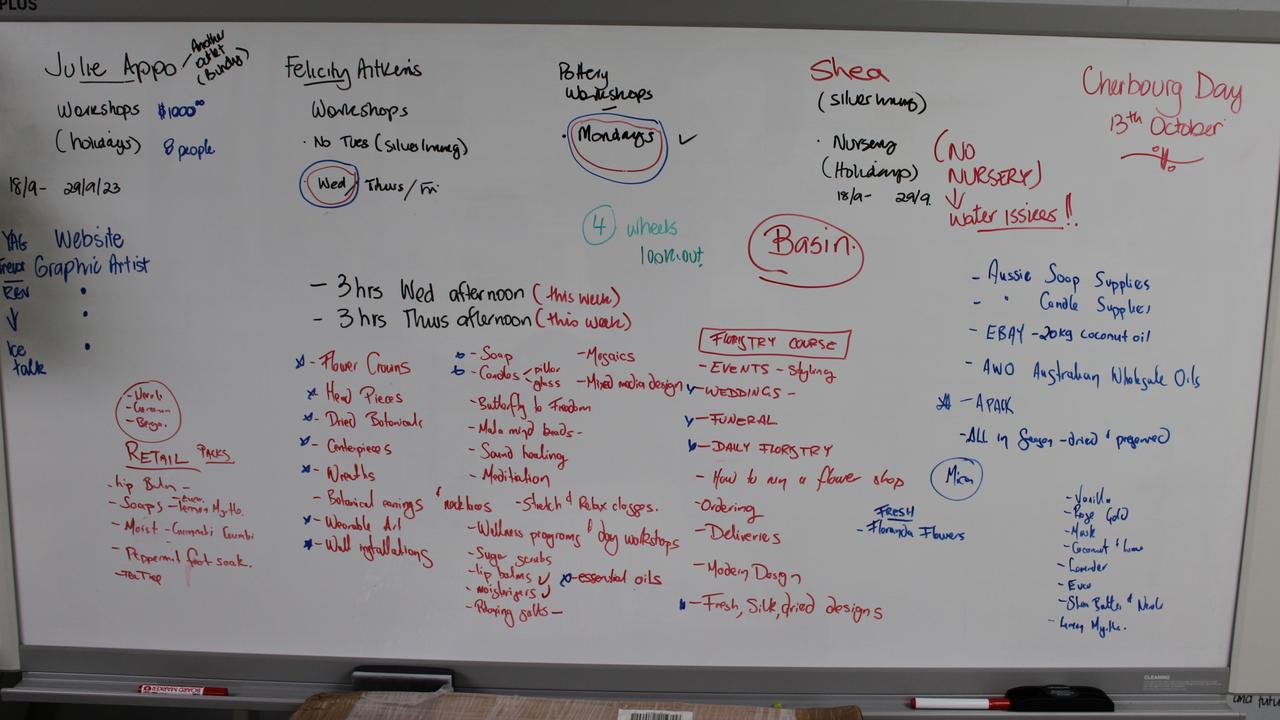

The forums grew into a Youth Advisory Group, with young people proposing and delivering projects such as repairing vandalism, yarning sessions with Elders and organising arts workshops to create products for sale through businesses in the surrounding region.

Ms Stewart said she had seen young people involved in the YAG improve in confidence and perform better at school, and suicides, while still occurring, had decreased in frequency.

“From the mouths of babes, they just kept coming up with all these ideas,” she said.

“Suicides are now getting farther apart, we’ve just had one but the last one was about a year ago.

“So that’s good to me, because we were just having them one after another.”

Gooreng Gooreng Elder and business owner Aunty Julie Appo has been providing arts workshops in the community organised by the YAG, teaching students how to create designs that are printed on umbrellas, shoes and bags that will be sold through her store Gnarla in Bundaberg’s Electra Court.

The YAG, with the support of council and Aunty Julie, are currently renovating a disused Emu Farm in the picturesque hills of Cherbourg overlooking Lake Barambah into a social enterprise to sell the goods created by the community.

Aunty Julie said the students were quick learners, and the excitement was palpable when they saw their designs take shape.

“They were extremely good students, and they loved it,” she said.

“They were so excited when they got their clothing, it was immensely exciting for them. And that, to me, is the greatest reward I could have.”

Ms Stewart said the successes borne from listening to the voices of those most affected by the problems in the community, and facilitating the implementation of local solutions, was a blueprint for how the First Nations Voice could deliver real change in addressing Indigenous disadvantage beyond the existing funding-based policies.

“We have to have that Voice, that’s the only way we can heal is to have our voices heard,” she said.

Existing approaches of governments imposing initiatives on First Nations people were exacerbating the intergenerational trauma from the lingering effects of colonisation that Ms Stewart said belied recent comments from leading No campaigner Jacinta Nampijinpa Price that colonisation had had a “positive” impact on Indigenous Australians.

“She’s denying our people,” Ms Stewart said.

“We‘ve got to strengthen our resilience, and that intergenerational trauma, we’ve got to deal with that kind of stuff.

“Don’t tell me how to do this, don’t tell me how to do that.

“For our people, it’s been done over and over; you were told when to eat, when to sleep, where you can and can’t go.

“We’ve got to let (non-Indigenous) people know that you’re giving us a hand up not a handout.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Cherbourg youth use their voice to overcome generational trauma