Native title could be reformed by the Uluru Statement of the Heart

As Australia prepares to debate constitutional change, Territory communities say the current laws ‘take away their dignity’. Read how here.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT is 1992. Bernard Namok Jnr and his sister sleep in the lounge of a two-bedroom home as their father sits drawing.

Their father sketches a flag that 30 years later would proudly stand behind the Prime Minister almost 3000kms away from its original homeland.

Bernard Namok Snr drew the Torres Strait Islander Flag, a creative endeavour to enshrine symbols of culture in one design.

“My dad wanted to include everybody, not only up here in the Torres Strait, but families that have relocated down to the mainland and places beyond that,” he said.

In that same year, another Torres Strait Islander man, Koiki (Eddie) Mabo, and several others, won a decade-long legal battle that dissolved colonial powers.

On 20 May 1982, Mabo and fellow Mer Islanders, Reverend David Passi, Celuia Mapo Salee, Sam Passi and James Rice began their legal claim in the High Court of Australia for ownership of their lands on the island of Mer.

With Mabo as the first named plaintiff, the case became known as the ‘Mabo Case’.

As part of his testimony, Mabo explained that his land was governed, it had boundaries, lore and was sustained by generations of his family.

He told the courts that his land had been passed through generations and when his father got old he would become its custodian.

On June 3 1992, the Mabo case successfully overturned the colonial notion that Australia was “terra nullius” (belonging to no one) and recognised the legal land rights of the Meriam people as Traditional Owners of the Mer Islands, north of the Queensland tip.

The lead Justice, the late Sir Gerard Brennan wrote in his judgment words that 30 years on continue to be at the centre of ongoing land rights cases across the nation.

“It is imperative in today’s world that the common law should neither be, nor be seen to be, frozen in an age of racial discrimination,” he wrote in his judgment.

“The fiction by which the rights and interests of Indigenous (people) in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country.”

In 1993 the Commonwealth government passed the Native Title Act of Australia.

TIMBER CREEK

The Mabo case set a precedence for several high profile cases in the Northern Territory, including Timber Creek and Blue Mud Bay with the latter returning not only land but tidal waters to Traditional Owners.

Northern Land Council (NLC) chairman Samuel Bush-Blanasi said the historic case proved colonial settlement was based on the lie of terra nullius.

“Native title needs reform. The native title process takes away our dignity. The way it is handled by the courts has been disappointing. Native title divides our communities and often makes things worse, not better. It needs to be fixed,” he said.

“We know it needs to be fixed so all the remaining claims can be finalised quickly. We don’t need other people to tell us we have always been here. We know that.”

Mr Bush-Blanasi explained the Northern Territory is the only jurisdiction to have a Land Rights Act, which means Aboriginal people own the land and almost all of the Territory’s coastline, giving veto rights to Aboriginal people over enterprises - like mining companies.

“You can’t do that with native title,” he said.

“Ever since Mabo, governments, miners, pastoralists, ministers and prime ministers have tried to cut back native title. We still need to move forward in this country.”

Following Queensland’s high court decision in the Wik case, the Howard government created a 10-point plan - known as the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 - that placed significant restrictions on native title claims.

However, in 2019 Ngaliwurru and Nungali people won another decade-long battle over native title.

The case covered the lands surrounding Timber Creek in remote Northern Territory and included compensation for damages to Country.

It was the first case to recognise the Aboriginal land as a spiritual being and as result the Commonwealth was ordered to pay $3.3m in compensation – $1.3m for spiritual loss and a further $2m in economic loss and interest on that economic loss.

However, further appeals reduced the economic value of the land and the final amount awarded was $2.5m.

At the time, NLC interim chief executive Jak Ah Kit said the finding was one of the most important since Mabo because “spiritual connection of Aboriginal people’s connection to their country was paramount in Australian law”.

In the media that followed, Aboriginal leaders agreed no amount of money could adequately compensate for cultural loss but the High Court’s recognition of the implications caused by ‘incursions and infringements’ on culture was of some comfort.

ULURU STATEMENT OF THE HEART

Thirty years on, Mabo and Namok’s stories find a new voice.

Recently Australia has reignited the debate of First Nations’ rights and calls for constitutional change.

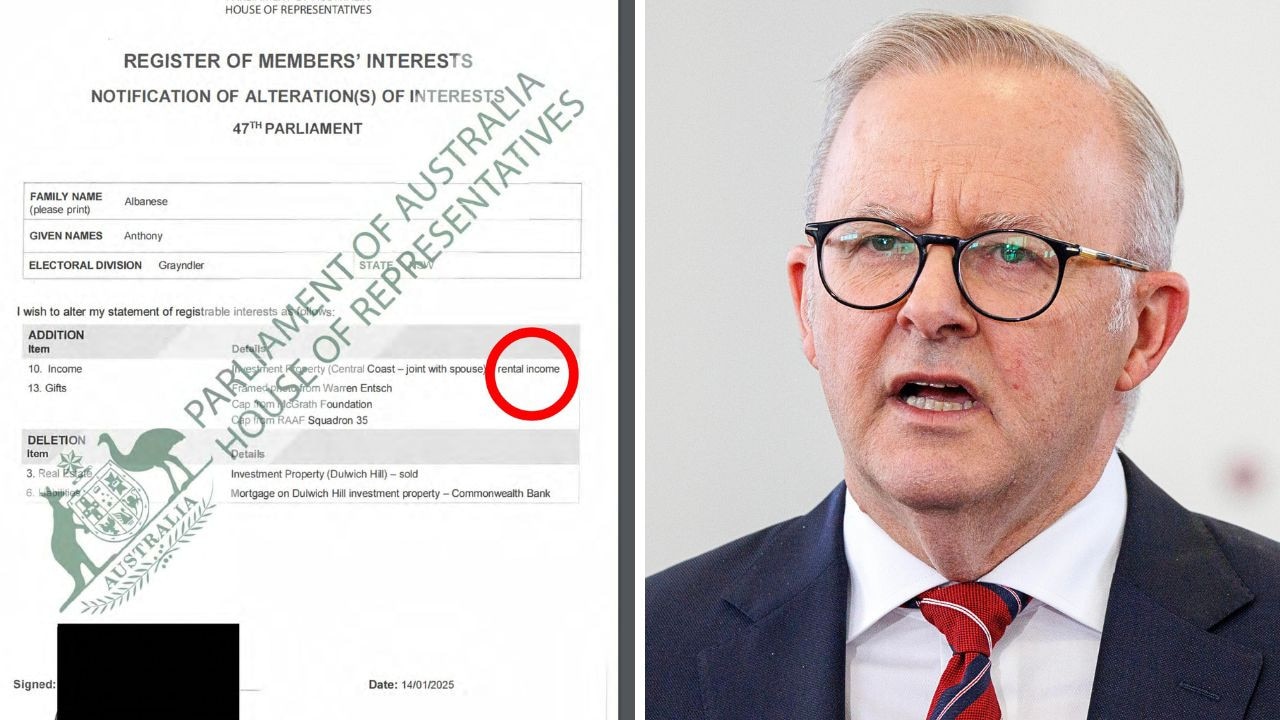

The night Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was elected he opened his victory speech by acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land on which he stood before committing to the Uluru Statement of the Heart.

The document codesigned with people from “all points of the southern sky” calls for a First Nations’ constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament.

“How could it be ... peoples possessed a land for 60 millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last 200 years?” the statement reads.

It extends the ideas of native title that have taken decades through the courts to be legally recognised and personifies land - ‘the ancestral tie between the land, or mother nature, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ - as the basis of ownership and sovereignty.

It calls for a Makarrata (the coming together after a struggle) Commission to “supervise a process of agreement making” between governments and First Nations’ people.

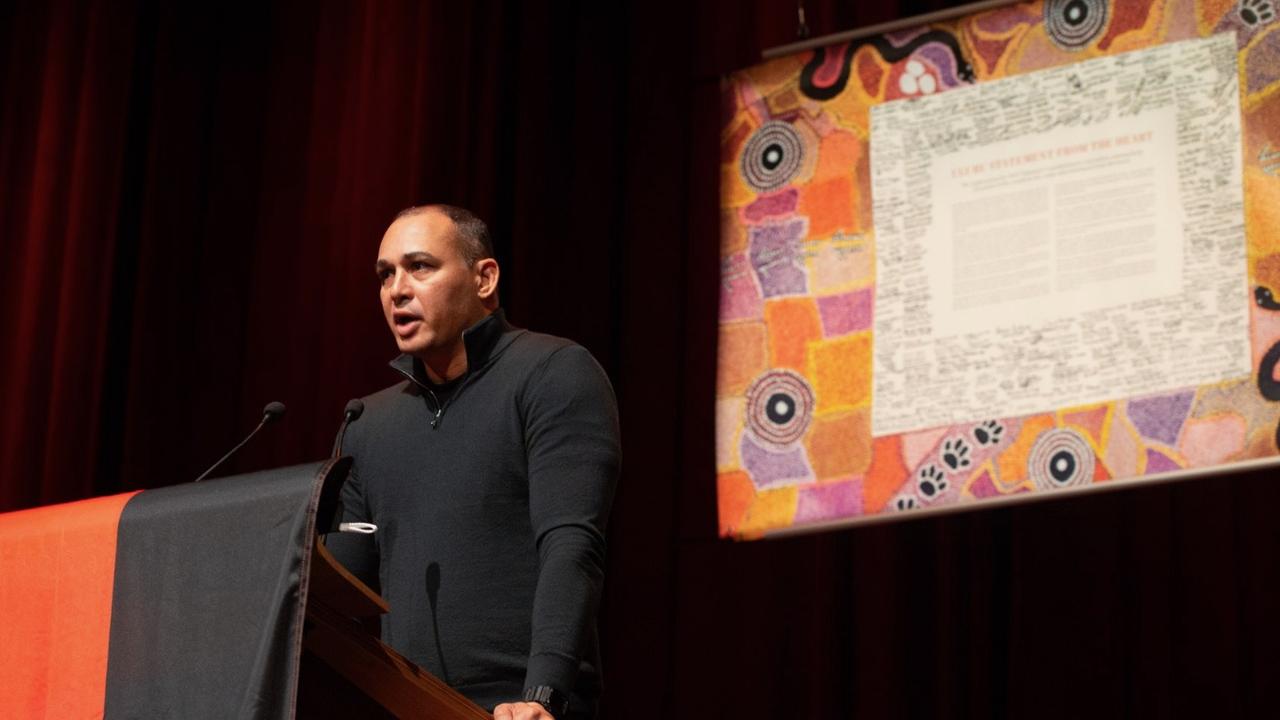

Uluru Statement of the Heart signatory Thomas Mayor said the current problems with Native Title and Land Rights Acts could be solved with an enshrined voice to parliament.

“The proposal for constitutionally enshrined voice is that it would be able to consult on that legislation, it would be able to give advice on how it could be improved and this is the same with many other things, including how justice is delivered,” he said.

“What we’ll see if the statement is fully implemented is a greater ability for us to influence laws, policies and programs so that we get them right.”

Assistant Minister Indigenous Australians Malarandirri McCarthy said Mabo Day was an important time to reflect on the pursuit of truth.

“Our government will continue this pursuit of truth in the values of the Uluru Statement – Voice, Treaty, Truth,” Senator McCarthy said.

“Communities, Elders, government and leaders can continue to walk together to find a better future in the best interests of First Nations people and all Australians.”

That little boy who slept as his father drew a flag, capturing inclusion, 30 years later sat with the community on Thursday Island and watched as it stood behind a new government, committing to the same symbols.

Bernard said the community was surprised to see their flag in the blue room - a room in the federal parliament that hosts parliamentary press conferences - after successive governments refusing to display them.

“I think everybody was surprised and they felt proud because they said it’s about time, you know, to see the flag flying beyond the prime minister,” he said.

“It brought all those memories from my childhood back, the late nights, and how all the things Dad was trying to capture are being transformed into what we are seeing today.”

Originally published as Native title could be reformed by the Uluru Statement of the Heart