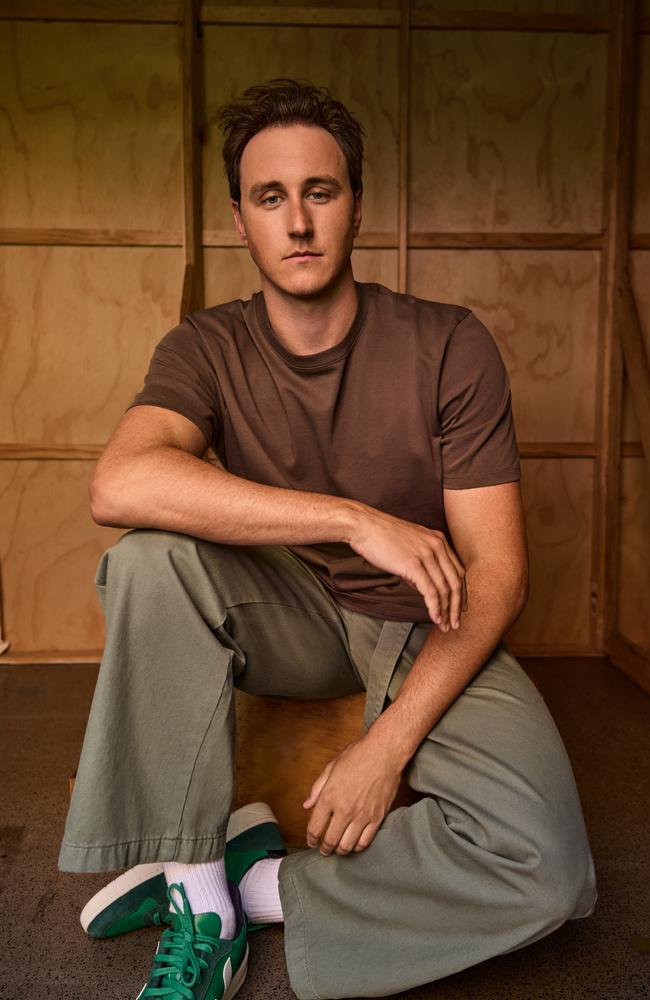

Bizarre response to swimmer Cameron McEvoy’s Olympic gold medal

The better swimmer Cameron McEvoy trained, the worse he performed on race day – so he made a huge change that resulted in an Olympic gold medal. And while his rivals want to learn his secrets, Australian swimming officials are yet to pick up the phone.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When swimmer Cameron McEvoy first touched the wall after his frenzied Olympic 50m freestyle final at La Defense Arena in Paris last month, his heart sank.

By its very nature, the race to determine the fastest man in the water is decided by mere nanoseconds.

For one of those nanoseconds, McEvoy thought he had ended up on the silver side of history. “My last stroke was like a panic,” McEvoy tells Stellar.

“It was one of the worst finishes I’ve ever done. I was in lane five, but I’ve been in lane four for every international competition [over the past year], so when I turned around and saw ‘2’ [marking the second-place finish] in lane four, my heart hit the floor.

“I was gutted, thinking this one stroke had lost me the Olympic fight.”

It didn’t take long for McEvoy, an astrophysicist nicknamed The Professor, to find himself corrected – and for a great Australian comeback story to be cemented.

Finally, after 12 years, four Olympics and an indefinite break from the sport, it took just 21.25 seconds for McEvoy to win his first Olympic gold medal. At the age of 30, he became the oldest Australian swimmer to achieve that feat, and the first to podium in the splash and dash.

Now back home, McEvoy says he expects it will take months to feel like himself again.

“Pre-Paris, as you get closer to that race, your world gets smaller and smaller,” he tells Stellar. “Reality outside of where you sleep, where you rest, where you eat and where you swim basically disappears and moulds into the peripheral.

“You do your race, and then all of a sudden there’s like a nuclear bomb flipping everything upside down. You go from a really tiny reality to the biggest one you can have.”

In the weeks since his return, McEvoy has been enjoying catching up with friends and family, and wearing something other than his swim kit.

“In my 20s, I was very into streetwear,” he says of his love of fashion. “I got into [Los Angeles brand] Rhude really early. But as I’m starting to get older, I’ve noticed a shift.”

While he got the chance to showcase that sartorial evolution in his shoot with Stellar, swimming remains steady in his thoughts. He’s already thinking about next year’s World Championships and how he will prepare for them. In large part, that’s because just under two years ago, his approach to the sport changed dramatically.

The Gold Coast-born McEvoy has been a swimmer since the age of five, and competing in the sport since he was nine.

So, he explains, for most of his life he has had a single regimen: getting up before the sun to make an early morning pool session, following that with a gym or physio session, and then heading back into the pool for another round of laps.

Rinse and repeat, six days a week. While McEvoy has specialised in the sprint distances, his training routine had him swimming up to 30km per week. At the start, that traditional training model was working. He broke Ian Thorpe’s records in both the under-16 and 17 age categories. Heading into the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, he was the favourite to win the 100m after setting new Australian and Commonwealth records.

But in that race, McEvoy finished seventh. He walked away vowing to work even harder.

Determined as he was, he found that hard work itself didn’t really pay off. “Rio kickstarted a seven-year period where, each year, the amount of effort I’d put into trying to make that breakthrough never matched the outcome,” he recalls.

“The more I got better at training, the worse my racing actually became in competition. That really burns you out mentally and physically.”

McEvoy’s analytical mind meant that he had always questioned the efficacy of the traditional training methods used by his coach and teammates.

“[In swimming] the dynamic is: the coach is the bus driver and all the athletes are the passengers,” he tells Stellar. “There can be an environment where, if you question or if you come in with a bit of curiosity, it’s not really met with open arms.”

Worse yet, his struggles in the pool were impacting his life outside of it: “I never got

to the point where it was anything serious, but when you’re in a community and an environment where you’re doing the best you can to follow along and it doesn’t work, and the justification is because it’s not in you, that spreads out into your entire life.

“You lose confidence in who you are as a person. That spills over into how you relate to people. You can get stuck down some pretty deep rabbit holes. And it’s very difficult to get out of. It certainly wasn’t a fun seven years.”

At the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, McEvoy won bronze in the 4 x 100m freestyle relay, but was knocked out in the heat stages of the 50m and 100m freestyle. The result, he says, was that he “got to the point where I didn’t want to see a pool indefinitely”.

Still, he wasn’t completely deterred and had one final hypothesis. What if there was another way to train? What if he could be his own experiment?

Inspired by his research into other sports – from gymnastics to rock climbing – and with the support of coach Tim Lane, who was happy to work in a collaborative relationship, McEvoy focused on building up his strength, mobility, flexibility and speed outside the pool.

“I decided it was a win-win,” he says. “If I did this program and it didn’t work out, then I’d have closure that the traditional training approach to my events had been very close to what I should be doing and I just didn’t have it in me.

“On the other hand, I could maybe find a new way to achieve the results I’ve always wanted to achieve.”

With his new approach allowing him to spend 90 per cent of his time away from the water, he adds, “It was closure either way.”

Within eight weeks of his new training regimen, the results were irrefutable. McEvoy was already swimming faster than he had in Tokyo. More importantly, his relationship with the sport had changed.

“The way I’m approaching swimming is completely aligned with my own character, my own nature as a person,” he explains. “That in itself provides a huge boost.”

It was a big financial risk, however, given McEvoy now faced the prospect of effectively being unemployed if he didn’t qualify for the long course world championship in 2023 (which he went on to win).

There was also a mixed reaction from coaches and fellow athletes. Many didn’t fully understand his new methods, he says, while a subset were “not believing in it”.

In Paris, McEvoy finally had his chance to show the world the results of the experiment, with himself as the guinea pig. He was nervous, but not as nervous as he had been in the past. As he saw it, he already had solid proof that what he was doing was working.

As he waited for the marshalling of his race, McEvoy’s competitors were strutting around like alpha dogs, trying to intimidate one another with their gestures and demeanour. McEvoy, on the other hand, was shedding a quiet tear with his coach.

“I spoke to him about how we’ve hit so many of our original starting goals and [that] I thoroughly enjoyed the last two years of training, the rediscovery of the sport,” he says. “And basically just thanking him for allowing me to get to this point.”

Of course, when McEvoy realised he had won the race, a far more ferocious side emerged. But he insists it was about so much more than just getting that elusive gold medal.

“There are achievements nestled within achievements,” he says. “You have the Olympic gold, but nestled within that you have the risk I took to approach this race in a very different way. And nestled within that, you have the lifelong childhood dream of wanting to make it in the sport and achieve the highest goal that you can, which is an Olympic gold. They all got kicked off at the same time. It was the biggest swim celebration that I’ve ever done. I’m a pretty reserved guy, but I was straight up on the lane rope, banging my chest.”

Back home, McEvoy has hung his gold medal on a statue of Apollo that sits in the living room of the home he shares with his partner, Madeline Bone. He has been bombarded with speaking requests and more sponsorship offers.

From the outset, Swimming Australia has been welcoming of McEvoy’s different approach to the sport, with its head coach Rohan Taylor giving him all the support he needed during his Olympic campaign.

However, post-Games, it’s been the attention from outside Australia, rather than from within, that’s surprised him, with many people looking for his insights.

“I haven’t had any interest from anyone in Australian swimming, as in an athlete or a coach,” he says, “but there have been a lot of international swimmers and coaches wanting to learn exactly what I’ve been doing.”

Of the local response, he reasons, “Australia just had our most successful Olympics, so if what you’re doing is working, then there’s not much necessity to try and seek out ways to improve on that.”

Nonetheless, McEvoy says the biggest advantage of his methods is minimising burnout, which in turn helps with longevity. He’s at an age when most swimmers look to retire, yet he’s seriously got his eyes set on not only the next Olympics in Los Angeles but perhaps Brisbane, too.

“It’s definitely a possibility if motivation is there and injuries aren’t,” he says of the 2032 Games. “Then, 100 per cent, that could be something I have in my future.”

Until then, he wants to share the results of his experiment with as many people as possible because, outside of his physical ability to succeed, he insists the greatest strength he has gained is his character.

“Growing up, I was never a fan of doing what the crowd does. What I’ve done in the last few years is, I guess, the best example to show that,” he explains. “The skill is being able to recognise that the path you’re on doesn’t lead anywhere – but still believing that there is a path that leads you to where you want to go.”

Read the full interview with Cameron McEvoy in the latest issue of Stellar. For more from Stellar, click here.

Originally published as Bizarre response to swimmer Cameron McEvoy’s Olympic gold medal