’Run out of options’: Melbourne author’s miraculous cure after battling terminal cancer

Like countless Aussies, Lucie Morris-Marr’s family loved their snags, bacon and ham – until she made a horrifying discovery.

Health

Don't miss out on the headlines from Health. Followed categories will be added to My News.

‘Hello?’ I said.

‘Oh, hello. Is that Lucie Morris-Marr?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good news. We have a liver for you.’

For a moment I had no words. I’d waited for this call for six months and had started to wonder whether it would ever come in time.

They were holding back the metastatic bowel cancer tumours in my liver with targeted antibody infusions every two weeks. I was stable, but the cancer was there. We had run out of options.

A major surgery just for the sake of removing the tumours for a third time would be traumatic and pointless, because we knew they were coming back. Radiation was not possible: I’d had as much as I could.

The drugs, which were keeping the cancer at bay, would have a shelf life. I’d been warned of that. I had loved and lost so many brave friends in the bowel cancer community, I desperately hoped for a different ending to my story.

Despite the odds stacked against me, I was determined to do anything to survive; to see my children grow up above all but also to complete my personal mission as an author and investigative journalist to finish my important book on the links between processed meat and many serious health conditions, including bowel cancer.

A liver transplant was my only chance.

But even this was an extraordinary option that came from a clear, blue sky earlier in the year. A series of incredible coincidences, luck, and new, emerging treatments and research coming together to make the Austin Hospital in Melbourne push forward with changes to their liver transplant protocol, just to try to save my life.

You see, historically metastatic cancer patients haven’t been given transplants in Australia — in very few countries around the world, for that matter.

It’s very new. It worries even the surgeons. Because the livers are naturally such a precious resource they cannot risk giving them to anyone who might not be able to bear them for long, when it could give someone else an entire lifetime. They have to make strict ethical decisions.

The reason it came to pass was just before Christmas 2023 I had been told I had seven new liver tumours just before I flew to England. Thankfully, I dropped a line to a cancer friend, a young barber named Mitch, who lives in Gippsland, Victoria.

By chance, a few years earlier, he’d got in touch because I wrote an article during Melbourne’s stage-four lockdown about what it was like trying to also deal with stage-four cancer. It was the exact advanced bowel cancer Mitch had. He was also battling to survive with similar treatments.

For some reason, I just wanted to know how he was. ‘How’s it going?’ I wrote to him in the Instagram message. ‘How are you?’

Thankfully, he’s a young chap and quick to respond.

‘Oh, Lucie, great to hear from you. I’m amazing. I’ve just become the first man in Australia to have a liver transplant with stage-four bowel cancer.’

I nearly dropped my phone. I’d asked about transplants before many times, and was told patients like me, with my condition, weren’t candidates. It wasn’t an option. All I could say to Mitch, with some urgency, was, ‘Mitch, please tell me who your surgeon was.’

I then contacted his surgeon, Associate Professor Carlo Pulitano, based at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, who had been allowed a special clinical trial to give liver transplants to the right candidates with colorectal cancer. So far, he’d only done one. Soon, he’d have done two.

By extraordinary coincidence, Mitch had gone to his local post office in Gippsland and mentioned he’d had a transplant. The post office lady had said, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s a young mother in this village called Amanda. She’s got four children under ten. She’s got advanced bowel cancer.’

Amanda became the second person in Australia to have a liver transplant with advanced bowel cancer. I would be the third.

In my case, Dr Niall Tebbutt, the head of medical oncology at the Olivia Newton John Cancer and Wellness Centre at the Austin Hospital, Melbourne, had become my new oncologist. I said, in our first meeting, ‘Niall, please can you send my notes to this surgeon in Sydney. I’m going to have to live there and wait for a transplant. They’ve offered me one.’ And he said, ‘Hang on a minute. Let me just speak to our team here.’

By 6.30 that evening, the team at the Austin, acknowledging that Victorian patients shouldn’t have to travel to New South Wales for a procedure they could do, agreed I would be the first to have a transplant in a Victorian hospital — whereas the other two patients were Victorians but they went to New South Wales.

When you get phone calls like that, the jubilation is overwhelming, but it’s quickly followed by immense fears. I would go through weeks of intensive testing, counselling. Everything to check there wasn’t a speck of cancer outside my liver. That was the rule. That was the protocol they were sticking to. And also, the cancer could only have been in the one place for at least a couple of years. Mine wasn’t unstable. It hadn’t been anywhere else since the primary tumour in my colon had been removed via resection in April 2020.

I fit the bill. I was young. It had been made clear to me again and again during the process that a transplant may not be a cure, that the metastatic cancer could return, often in the lungs.

The immune suppressants could also cause skin cancer, plus kidney issues. There could also be possible bile duct issues. All these, however, would hopefully be treatable matters and with careful monitoring I felt I could deal with any blips.

‘My alternative is guaranteed death, so I’ll take it,’ I said to surgeon Marcos Perini, who had been placed in charge of developing the new colorectal cancer transplant protocol, as I signed the transplant permission forms.

He told me to stay active and keep my phone on. And then everything fell silent.

‘Do it, Mummy’

As I got up from the sofa, I saw my daughter walking towards me in the kitchen. In that split second, she didn’t yet know. It was hard. She was only 14, just so young. She’d already had five years, a third of her life, with a mother with serious cancer and going through so many treatments. I had to tell her she had to be brave. I had to go through one more surgery. Tears welled in her eyes.

My son, aged 16, beautifully dressed in his air force cadet uniform, came through the door so handsome, dazzling, from his evening parade. I led him to my room, and we sat and we cried and we laughed. I said it was time. I would have to go in an hour.

We had an hour together.

I’d already been told I had a three per cent chance of dying on the operating table. The pain and tears — as a mother, you just want to solve it. You just want to do anything to resolve that pain when it’s your child. You don’t want to leave them. It’s the last thing you want to do.

I had to reassure them, but I also gave them a choice. I said, ‘Either I can stay now, and you don’t have to go through the darkness. You won’t cry for most of the night. But you may only get one more trip, maximum two, around the sun with me. If you let me go, you’re going to have to spend a night or so in the darkness. Be brave and tell me to go, you may get forty years of trips around the sun with me. What should we do?’

‘Do it, Mummy,’ my son uttered. My daughter just nodded, more tears welling.

I wanted them to feel that they were part of the decision, because this is why I was doing it. I was doing it for them.

I knew of the risk. It was a massive risk. Part of me just wanted to stay with them, investigate trials at Peter Mac, or stay tracking as I was. There are so many trials going on around the world. Surely someone could cure cancer. After all, someone quickly found the vaccine for Covid.

But I knew deep down I’d done the risk calculations. I’d spoken to other transplant patients. I’d actually had other consultations, opinion consultations, with liver surgeons who had no skin in the game. No possible competitive ego motivations, which can happen between hospitals, between men, between humans. They said, ‘Do it. Take the chance.’

I mentioned it to Betsy Post, a community leader of Colontown — the biggest colorectal cancer forum in the world, which I’d been very much a part of in mentorship of other patients — whose sister died of colorectal cancer. When I said here in Australia the transplant was free and I shouldn’t have to wait more than a few months, she couldn’t believe it. She said, ‘Do it. Take it. Here in America, you’d have to sell your house because the insurers don’t always pay.’ And of course, some people aren’t insured. She said, ‘To wait for a deceased donor in America could take one to two years, when it’s too late anyway.’

With no stone left unturned I even met with author and former broadcaster Derryn Hinch, now eighty, who’d famously had a successful liver transplant thirteen years earlier, led by surgeon Bob Jones, now the head of the Liver Transplant Unit at the Austin. ‘You’ve got this, go for it and don’t look back,’ Derryn said. The one thing the Human Headline certainly knows about more than most is staying alive. His words were like rocket fuel. It made me feel so lucky to have this option, and I knew the surgeons were experts.

My children walked me out into the front garden, my husband pulling the suitcase towards our car in the street. We hugged for a final time in the driveway, in the darkness. I knew there’d be tears as soon as I went. A dear friend, thankfully, had dropped everything to be with them for the night. She was waiting for them inside with hot tea and toast. I knew they were safe.

Again, they talk about cancer patients being brave, but I’ve never felt brave before. I’ve simply got on with it. Because you do what you have to do. But even I admit, walking away from my children felt like I needed every brave bone in my body to just get out the gate.

As we got to the car, I could see their shadows waving. I’d like to say the bright moon that night lit up their faces, to make the perfect Rembrandt-style image for you. But the trees were in the way as we drove off, and I couldn’t see my children. They were already alone in the dark.

We drove away in silence. All the way north, north through the suburbs of Melbourne to reach Heidelberg. Through Camberwell, along Burke Road, up through Kew and Ivanhoe.

We pulled up outside the emergency department, where I’d been told to present myself.

The waiting room was packed with probably forty or fifty people, but I was whisked straight in and taken away to a ward — a ward I would soon know very well: Ward 8 West, on the eighth floor. It’s where the transplant patients go.

They X-rayed me. They did bloods. It was just after midnight. I would be asleep by six. And incredibly, those hours went very fast. My husband holding my hand, dozing slightly in the chair. Me, sending messages to family in England, informing them of what was happening. And of course, messages to my children for when they woke up.

With word spreading among my family and friends, I was told in messages that multi-faith prayer vigils were already beginning all over the word. My dear friend Tessa Sullivan, Honorary Consul for Thailand in Melbourne, had informed the Thai Buddhist monks based in the Buddha Bodhivana Monastery, deep in the forest of the Yarra Ranges near Warburton.

They knew of my fight, having recently given me a personal blessing at Tessa’s home. Further afield friends of the Jewish, Muslim, Catholic and Anglican faith would spend the entire night, UK time, praying for the duration of my operation.

I could not have had more support, and willingly opened my heart to their prayers and kindness.

The porter came. ‘It’s time to go.’

My bed was wheeled along the corridor to the lift and down to Level 2, to where surgery was and where I would be in intensive care.

Sooner than I hoped, we turned a corner and they said, ‘This is where you say goodbye to your husband.’

We just looked at each other, held hands, and I told him, ‘I’ll be okay. See you later.’

He said, ‘You will be okay, and I will see you later,’ before my journey continued to the small side room where I could see them busy prepping the theatre. Bright lights, metal.

Technical workers were already prepping me. The surgeons would not be there until perhaps seven. They wanted me asleep, to set me up, to make sure I was stable, to be ready for the operation to begin. A precious package that had my name on it was now in the theatre. A liver on ice in an Esky, possibly having been flown in by private jet. By now, it had been placed in a machine perfusion device, which keeps the liver pumping and alive. The contents of the package was waiting.

‘You’re going to go to sleep now, Lucie,’ the anaesthetist said. I don’t remember any more.

‘Just breathe’

‘Lucie, you’re on a ventilator. Just breathe.’

This had been my worst fear out of the entire procedure.

They warned me I would have to be woken up and ventilated, which is rare, very rare. They have to do it. They have to 100 per cent know that you can breathe on your own when you’re awake. My nine-hour surgery had been a success, but then they’d kept me asleep on the ventilator for my body to stabilise and relax for another seven hours. And now it was time to make sure I could breathe on my own.

‘We’d like you to stay on it as long as possible,’ the anaesthetist said calmly.

It’s funny how the phrase ‘It’s never as bad as you think it will be …’ is so often true. It wasn’t one of those face mask type of ventilators. It was a tube that went in my mouth and down my throat.

I breathed calmly over it, and she said, ‘If it’s getting bad, just let me know.’

I managed a few more minutes of just breathing, focusing on the Yarra Valley campsite and the river I love so much, and floating down it with my children. The light was coming in, dappling on the surface. My hand went into the cold water. I was there. I wasn’t in intensive care.

‘I think that’s all I can do now,’ I mumbled to the anaesthetist.

‘That’s fine,’ she said, and with one movement it was removed very easily.

I was breathing on my own. I was alive. The operation had worked.

I asked to call my husband. They put the phone to my ear. ‘I did it. I did it,’ I said down the line. ‘We did it.’

‘I’m so happy,’ he said. ‘They let me in earlier. They let me hold your hand briefly when you were still under. I’m so happy.’

That’s all I could manage. I just wanted him to know, from me, I was okay.

I would eventually call Mitch too; his openness about his pioneering transplant had now played a serendipitous role in saving not just one mother, but two.

Of course, even though I was okay, there was still a long way to go to really fully come back to life. I may now have been cured of terminal cancer, which I’d fought for five years, but in the following days, I would remain in intensive care. “Recovery doesn’t always go in a straight line,” the excellent liver team kept telling me. They would be right.

Tubes, a mainline in my neck, a massive drain around the wound. Other tubes in my hand. Multiple medications and infusions happening at all times.

Amazingly however a physio, even on that first day, helped me to a chair with all the tubes as part of the protocol to make sure your body doesn’t clot, to keep moving. I even managed, with the help of a frame, to walk some steps around intensive care, and then straight to bed again. Thankfully, the daily ocean swimming and walking I’d done while waiting for the transplant helped.

The next days are now quite a blur, but they involved a lot of pain, a lot of sickness, as my body tried to grapple with the surgical assault.

At one point, they wheeled me out into the terrace just off intensive care, and I felt the sun on my cheeks. It was the first time I was able to pause and take in this incredible, miraculous gift — the result of an Australian passing away and being so generous, thinking of someone else. Having signed up to the organ-donation program, possibly, and either way their family would have been asked if they gave permission.

I put my hand over my wound for the first time and said, ‘Thank you.’

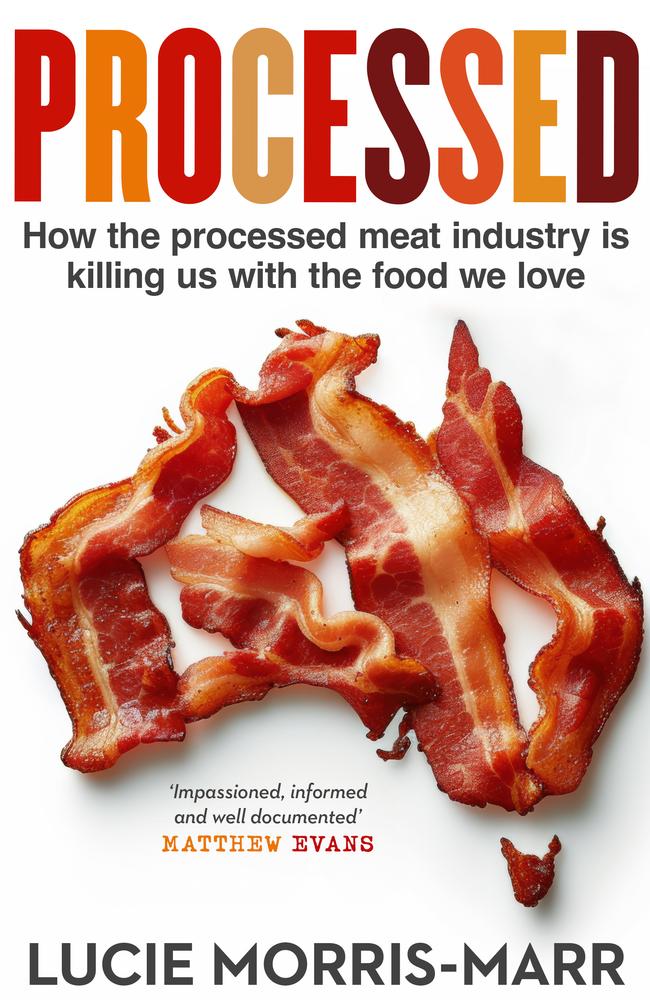

This is an edited extract from Processed: How the processed meat industry is killing us with the food we love, by Lucie Morris-Marr (Allen & Unwin, February 2025).

More Coverage

Originally published as ’Run out of options’: Melbourne author’s miraculous cure after battling terminal cancer