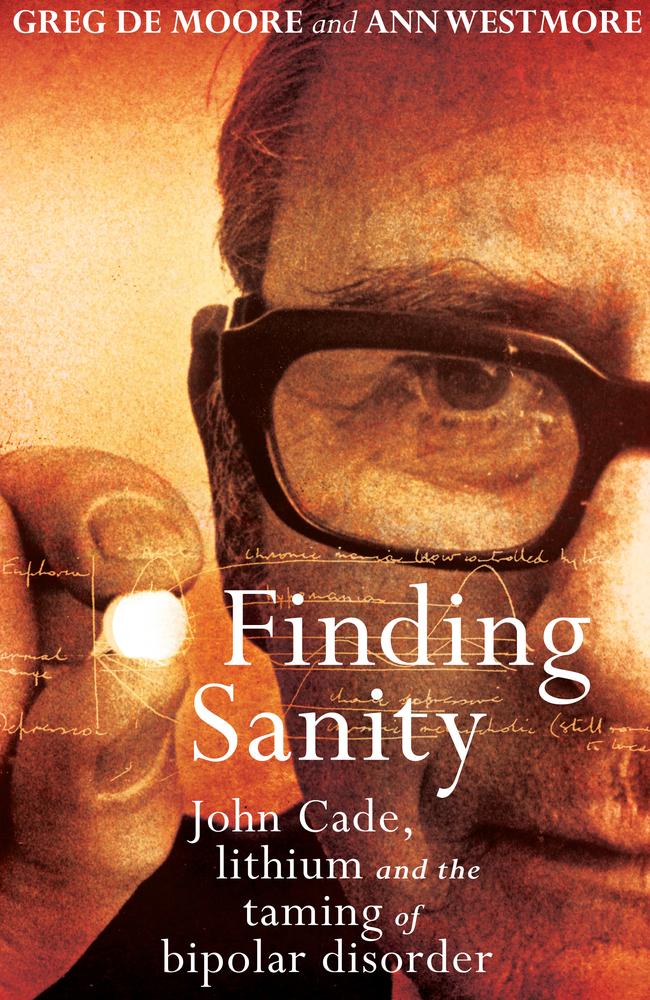

Finding Sanity: How an Australian doctor discovered the first drug to treat mental illness

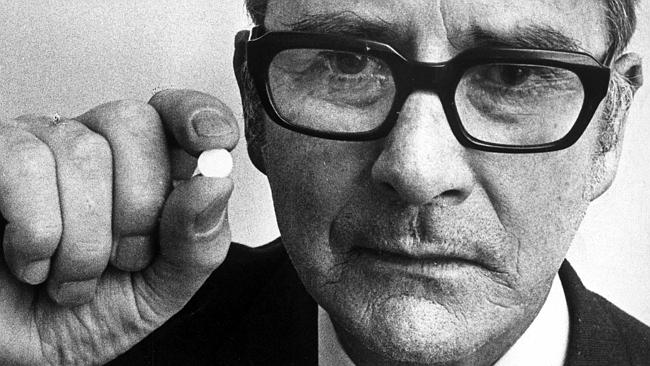

AUSTRALIAN doctor John Cade changed the course of medicine, with a drug that transformed the lives of millions. His story has been told for the first time.

Health

Don't miss out on the headlines from Health. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AUSTRALIAN doctor John Cade changed the course of medicine with his discovery of lithium; yet most people have never heard of him.

Lithium is the penicillin story of mental health. It was the first effective drug discovered for the treatment of a mental illness, and it is, without doubt, Australia’s greatest mental health story.

In Finding Sanity, the first biography written about John Cade, his story is finally told.

With a bit of luck and a lot of urine and guinea pigs, he stirred up a miracle.

News.com.au has been given this exclusive extract.

***

IN 1946, John Cade’s starting point was a belief that mania was caused by an excess of a naturally occurring substance in the body, a type of intoxication if you like. And that depression was the opposite — a deficiency of this naturally occurring substance.

Now of course, all this was wild speculation because he certainly had no idea if such a substance existed in the body and, even if it did, he had even less idea of how to find it. Still, this was his launching point.

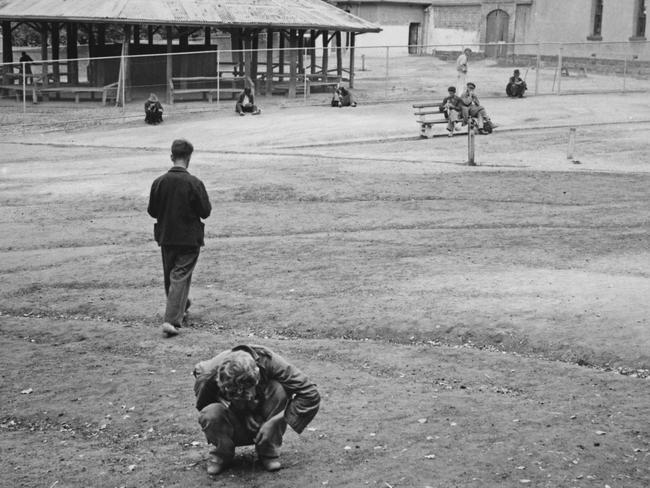

John Cade was a pragmatic man. The practical question he had to answer was this: how could he possibly know what was happening inside the manic-depressive brains of the men for whom he cared?

There were no modern imaging devices to chart the structure and size of the brain in 1946. Repeated blood tests were intrusive and, anyhow, none were known to point to any specific type of mental disorder. What could John examine in order to find this imagined substance that caused mania in excess? His answer, perhaps surprisingly, was urine.

Jean Cade remembers the start of her husband’s experiments: “He came to me and said: ‘I’ve got to do some research on why these patients have got different illnesses. I’d like to find the melancholias first. I’ve got an idea that might come to something if I save a lot of jars.’”

Why her husband needed jars for this work was not immediately apparent to her, but soon the jars started accumulating.

John travelled to the city and purchased numerous bulky glass jars from McEwans, a department store in Melbourne. His wife, seeing her house, then garage, bulge with these jars, was less enthusiastic. ‘We had no money, I kept telling him.’ But John, on a determined line of thinking, was oblivious to his wife’s concerns.

“I was horrified, we couldn’t afford it. He just said: ‘we might be able to use them afterwards for pickles’.” This, undoubtedly, was a private joke of John’s, for as soon as he had acquired sufficient numbers of jars, John started to fill them with urine from his patients.

To examine the urine of his patients might seem bizarre to us but it would not have seemed the least bit odd to John Cade. Doctors had long considered urine to be the portal into a man’s body and mind.

To the average person, urine is hardly worth more than a passing — if sly and mildly distasteful — look. Whatever anyone else might think of urine, it was about to receive John’s complete attention. It was an examination of urine that led him to a series of experiments that would change the course of medical history.

John’s thinking ran like this: if mania was due to an excess of a chemical circulating in the body, then just maybe some of this excess chemical might be expelled in the urine. What he was hoping to find was an excess of this putative chemical in the urine of manic patients. If he could prove this, then, it might set him on a path to find a treatment for mania.

***

John had no laboratory so he started work in his garage in the backyard — not the first or last time something revolutionary in the world of science would miraculously unfold in a garage.

The jars accumulated, filling the shelves while he searched for a laboratory. As it turned out, there was one literally less than a hundred metres away over the back fence; an empty pantry in a new ward just built but as yet unoccupied.

Jean remembers the day he proudly showed her his find: “He helped himself to the pantry of this new ward. He took me over to look at it: ‘Look, look I have a bench and hot and cold water”, everything he needed. And so it began from there.’”

Everyone called this makeshift laboratory, “the shed”. The shed — in the timeless tradition of Australian men — was where John kept the tools of trade for his experiments. To get to the shed from the Cade house was a short stroll: out through the gate in the back fence, past the chook pen with its Australorps and Rhode Island Reds, along the gravel path that John took every day.

John was just about ready to start his experiments, but he needed one further vital piece of equipment — something cold in which to store and preserve his ever-increasing number of jars of urine.

In a decision that horrified his wife, but seemed natural to John, he chose to store the bottles of urine in the refrigerator in the kitchen of his house. The Cade fridge, with its creamy, rounded shoulders, was a Frigidaire model — an Australian post-war symbol of middle-class wealth; The Australian Women’s Weekly beamed advertisements displaying the modern fridge’s exceptional capacity to keep fresh and cool homemade jams, butter and beer.

The importance of keeping urine chilled seemed to have escaped the magazine editors. None of this impressed Jean, but her protests failed to deter her husband; utility always trumped fashion. Each patient’s urine was decanted into a screw-top bottle, numbered and shelved.

Beneath the butter sat the urine of dozens of patients: amber brews drawn from mute and immobile melancholic men; fizzing brews from over-the-top manic men that needed a baker’s dozen of nurses to pin down. Every time anyone from the Cade family opened the Frigidaire door, there, staring at them, were the bodily fluids of several dozen mentally ill men.

For Jean and John’s two boys, it was perfectly natural to push aside a bottle or two of urine to find the cheese, all done with the casualness of childhood. “To us it was all normal. We wouldn’t have known whether everybody else did or didn’t have urine in their fridges at home.”

***

John, almost comically, had glass jars full of urine multiplying and accumulating. Now what to do with them? Well, he did something we might consider cruel, but was natural to an experimentally minded doctor with a hunch.

He had no sophisticated equipment to analyse urine, even if he knew what he was looking for. Crude and simple, with shades of Dr Moreau, he decided to inject the urine he had collected into guinea pigs to see how the urine might affect the animals.

Sometime in 1946, John obtained guinea pigs from nearby Mont Park asylum and caged them in his newly acquired “laboratory”. His second son David still treasures the memory of walking into the pantry and seeing his father with the guinea pigs:

“The guinea pigs were in cages, but we also had some at home. They got through a lot of kitchen scraps. I remember Dad handling one of them on his left arm, and stroking it; they were tame from constant handling. They were good-looking: tan, black and white. My favourite was a tan and brown one.”

Jean adds: “We had guinea pigs in the shed. Lots of guinea pigs. As they died we’d get some more. He was good to them. He’d call them darling. And say: ‘Don’t you mind me doing this’ as he injected them.”

John would draw urine from the stored jars into a syringe. The syringes were not the lightweight plastic jobs of today. They were hefty and industrial in design, constructed of glass and metal.

They clanged and scraped when assembled, and when sterilised in pots. He would gently hold and turn over the guinea pigs, and inject the urine into their abdominal cavities. It takes little to imagine him moving assuredly and with celerity from jar of urine to syringe to animal.

John was looking to see if urine from a manic patient might affect a guinea pig differently to urine from other patients.

One by one, regardless of the diagnosis of the patient, the guinea pigs perished. And, practising what he’d done all his professional life, and what any respectable doctor might do, he performed a post-mortem on every animal, looking for a deeper understanding of what caused mental illness.

As the guinea pigs died, he procured more animals and started afresh. Each evening after work and when he had time during the day, he returned to this pantry and worked alone with his animals.

John was well aware that what he was doing was remarkably crude. So, at first, he kept quiet about his work, telling only a select few who needed to know.

Today, no one would consider whipping out, buying dozens of jars, filling them with the urine of patients and then injecting the urine into guinea pigs. It sounds archaic and primitive, and it was an era of experimental crudity that was coming to an end.

But somehow his upbringing, his pragmatism and his insatiable curiosity gave rise to this hands-on experimentation; it had been the shaping of a lifetime that led him here.

***

In 1946 John was a man in a hurry. Later in life he wrote: “I returned from three and a half years as a POW of the Japanese mourning the wasted years and determined to pursue the ideas that had germinated in that interminable time.”

John pursued a number of leads over the next 18 months. His early experiments suggested to him that the urine from manic patients was more toxic than urine from other patients, and therefore killed more guinea pigs.

As it turns out, John’s belief that manic urine was more toxic was false — urine from a manic patient is no more likely to kill a guinea pig than any other sort of urine. This mistake, like countless others that scientists have made over the centuries, was a fortunate one, as it spurred him on, and he continued unhindered with his idiosyncratic research.

John’s mind bubbled in anticipation of finding something in the urine of manic patients. What could it be? There are two known toxic substances in urine — urea and uric acid. Both are breakdown products, halfway houses of the body’s metabolism. Perhaps one of them was the elusive chemical toxin he was after.

Some of John’s chemical experiments make for intriguing reading. Left for posterity, they resemble the scribbles one might find in a high school chemistry notebook. At one point he adds three cubic centimetres of hydrochloric acid to every 100 cubic centimetres of urine to get a precipitate and then he takes us through the steps of filtering; there is more than a whiff of a home economics class when John writes that he adds “one level teaspoon” of charcoal for every 100 cc. And then, when he reminds himself to “shake for five to 10 minutes”, he appears in our minds, absurdly, behind a cocktail bar as if preparing an evening gin and tonic.

When finally done, John hit upon the idea that urea was the toxic element in all the urines that killed the guinea pigs. The conclusion he drew was that there was more urea in manic urine than in the urine of patients with other mental conditions.

But when he tested this idea he found that manic urine had no more urea than any other urine. He was stuck.

To get over this setback he postulated that urea and uric acid might work in tandem to make the urine of manic patients more toxic.

He started to work on uric acid, and this is where his experiments grew fascinating. To make up different strengths of uric acid he needed to convert it into a substance that he could more easily manipulate.

On its own, uric acid would not dissolve in water. To persuade it to do so, John added the element lithium to uric acid to make up a compound called lithium urate. And that is where lithium comes onto the scene, en passant, almost apologetically.

In the course of trying different combinations, as any good scientist might, John then injected lithium alone, as lithium carbonate solution. That’s when he drew breath, and promptly forgot everything else, except for lithium.

When John injected the lithium, the guinea pigs seemed restful. In one memorable description he said that he simply lifted one of the guinea pigs, turned it over, and placed it gently on its back.

Instead of doing what any respectable guinea pig should do when placed in such a vulnerable position — turn over and stand up in protest — this guinea pig simply lay on its back and looked vacantly at John. He repeated this experiment again, and the response was the same.

Behind John’s unfathomable face something stirred, a shaft of comprehension.

Uncharacteristically agitated, he summoned his wife, a day she remembered. “He called me from the kitchen, with great excitement, to come and see.” And John showed Jean how, without any difficulty, he could turn a guinea pig over on to its back and move it around without any protest.

These loveable rodents, normally a mass of vibrating muscle and fur, now with lithium in their bellies, would lie with equanimity on their backs, staring with soft eyes at John while he gently prodded them with the stub of his index finger. He had never seen them behave like this. They seemed alert, but they were calm.

So what was going on here? John thought that the lithium was calming the rodents. Looking back, it is more likely that the guinea pigs were ill, due to the toxic effects of an excessive dose of lithium. But John didn’t know this. What he saw was a rodent stilled by lithium.

There are times, when reading John’s carefully written accounts of his experiments, that it is virtually impossible to follow his line of thinking. He was wrong when he concluded that urine from manic patients was more toxic than other urine. He was also probably wrong when he thought the guinea pigs were resting after lithium.

Many of his observations cannot be replicated when tried today, so reproducibility, the gold standard for scientific sturdiness, is absent.

But none of this mattered. Because when John nimbly sifted through the options, his mind intuited something remarkable: that giving lithium to guinea pigs soothed them in a way that was worth pursuing. There was something special about lithium.

This is an edited extract from Finding Sanity, by Greg Dr Moore and Ann Westmore, published by Allen & Unwin and available now.

Originally published as Finding Sanity: How an Australian doctor discovered the first drug to treat mental illness