‘From fun to deadly very quickly’: Dangerous bedroom act on the rise in Australia

It’s a sex act that can go “from fun to deadly” in a matter of seconds – and a growing number of young Australians are taking part.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Nearly a third of young Australians are engaging – for pleasure – in a sex act that can go “from fun to deadly” in a matter of seconds, new research has found.

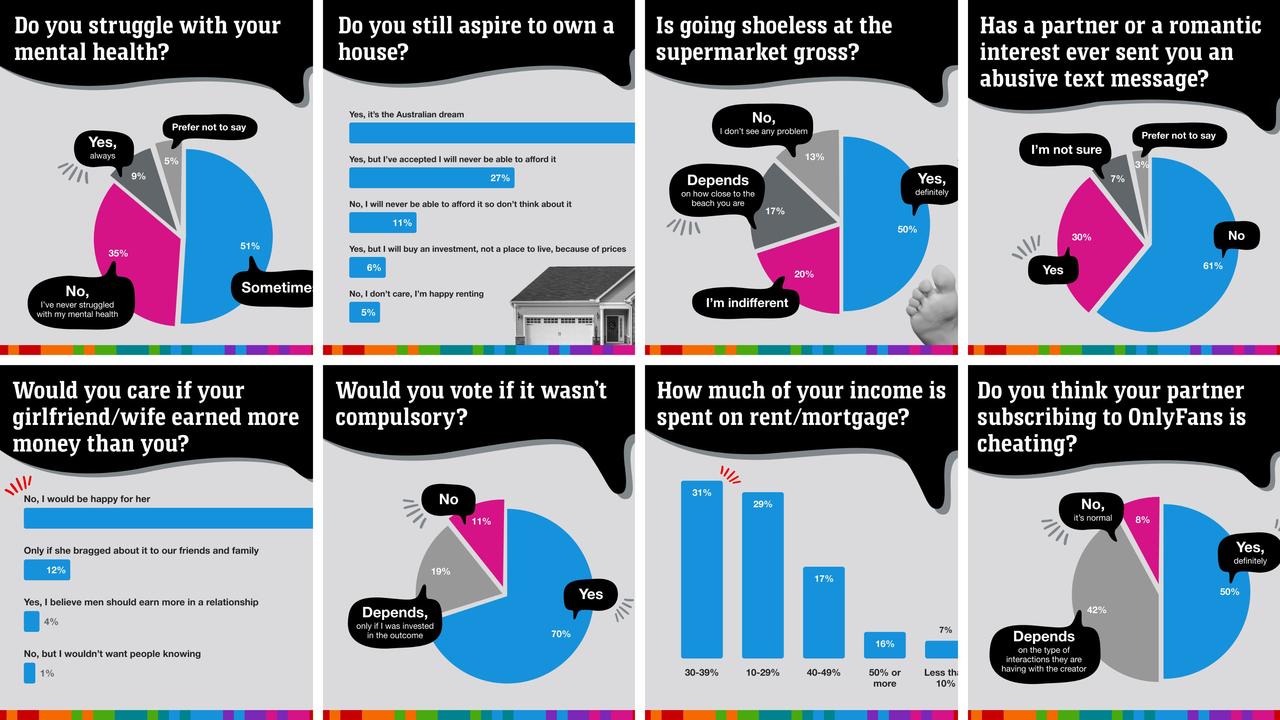

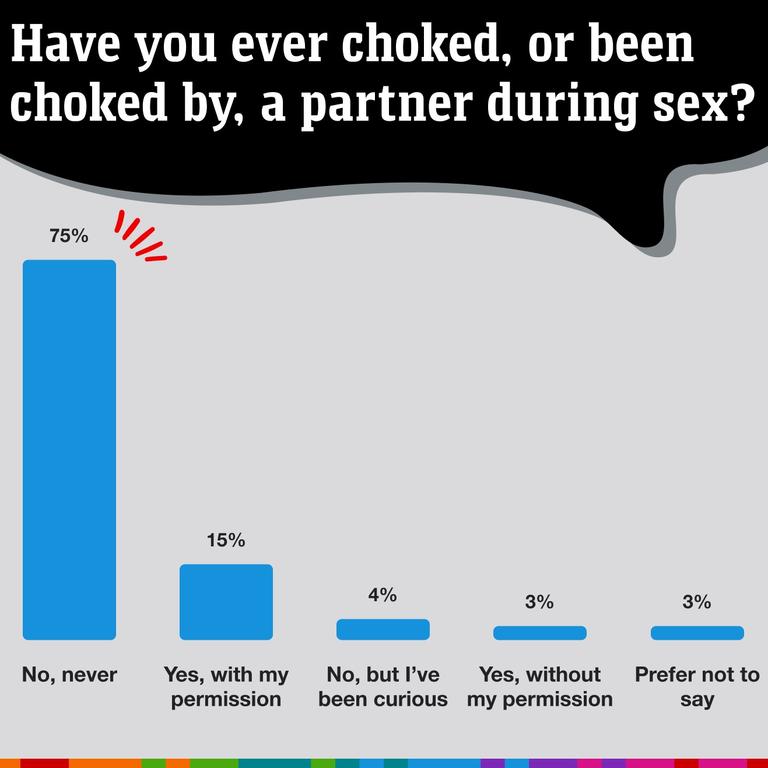

Of the more than 54,000 people who took part in The Great Aussie Debate – a wide-ranging, 50-question survey news.com.au launched earlier this year, uncovering what Australians really think about everything from the cost of living and homeownership to electric vehicles and going shoeless in supermarkets – 30 per cent of 18 to 29-year-olds had engaged in strangulation during sex.

They were also the generation with the highest rate (3.31 per cent) of it happening without their consent.

Defined as when a person’s breathing is stopped or restricted by the use of hands, other body parts or ties around the neck, the act, commonly referred to as “choking”, cannot be performed safely during sex, police, doctors and researchers have said.

Though the practice isn’t new, Gen Z’s increased acceptance of it as part and parcel of “normal” sex has become a central concern for experts.

As Teach Us Consent founder Chanel Contos asked in her National Press Club address, “How can it be a significant indication a man is going to kill you has become commonplace in the bedroom?”

First and foremost, the University of Melbourne’s Professor Heather Douglas told news.com.au, “I think we can blame the extraordinary accessibility of online pornography and sharing over the internet” for the rapid rise of sexual choking.

In a survey led by Professor Douglas of 4700 18 to 35-year-old Australians, pornography was the primary source (61.3 per cent) of participants’ exposure to information or depictions of the practice, as has fear of being perceived as “vanilla”, movies (40.3 per cent), friends (31.9 per cent), social media (31.3 per cent) – where memes have minimised and even romanticised the risks, and discussions with potential partners (29.2 per cent).

Prof Douglas’s findings showed two things, Women’s Health NSW Senior Project Officer Jackie McMillan told news.com.au: “The idea that it is safe to do, and the idea that all your friends are doing it.”

“And when more people are introduced to a sexual practice, they may also go on and try it with their future partners, which can lead to increased prevalence,” Ms McMillan said.

“When people think sexual choking is normal and routine, it can become decoupled from the health and safety risks associated with it, and it can reduce the impetus on every sexual participant to get informed, affirmative and specific consent before they try doing it.”

Male Great Aussie Debate respondents were most likely to be curious about engaging in choking during sex (4.45 per cent), while fewer than 2 per cent of women (1.84 per cent) said they had any desire to partake.

Of those who had engaged in choking during sex, 12.5 per cent said it had been with permission, versus 2.3 per cent who said it had been without. Non-binary Australians (8.15 per cent) were most likely to have been subject to choking without their consent, followed by women (4.69 per cent) and less than 1 per cent of men.

Irrespective of consent or the lack thereof, the harms and risks associated with strangulation are well-documented: everything from the immediate – bruising or swelling to the neck, blurred vision, dizziness or light-headedness, difficulty swallowing – to long term.

Of greatest concern to experts is brain damage, which can take days, weeks, or even years to manifest. No matter how briefly, restricting blood flow to the brain can cause permanent injury like cognitive impairment or a stroke.

Prof Douglas pointed to research that, over a month, compared people who had been consensually strangled during sex on three or four occasions with those who had never been strangled.

“The people who were strangled showed brain damage,” she said.

“They were slower at solving problems, had more memory issues and even the structure of their brains looked different.”

There is also growing evidence that, much like the cumulative harm of repetitive head injuries on football players and boxers, hypoxic/anoxic brain injuries from sexual choking also add up, Ms McMillan said, and can lead to long-term cognitive problems.

A “fine line” exists between the amount of pressure applied during fatal and non-fatal strangulation, Prof Douglas said.

Even the “relatively low” amount of force it takes to open a can of soft drink, when applied to someone’s throat, is enough to cause unconsciousness and risk brain injury.

People who are engaging in strangulation during sex, she continued, are unlikely to be “experts on pressure use” – a survey of 169 Australian university students published last year found that most considered it to be risk-free.

“The timeline between pleasurable and fatal sexual choking is measured in seconds, not minutes,” Ms McMillan said.

“It can move from being fun to being terrifying and deadly very quickly. If you throw drugs or alcohol into the mix too, you can imagine how quickly stuff can go wrong.”

Ms McMillan noted there is also “legal risk” to sexual choking.

Under NSW law, “having someone’s consent doesn’t protect you if you cause serious harm or the death of another person … even if you use harm-reduction techniques like ‘moderate’ pressure and communication throughout”.

“If you’re going to keep (engaging in) sexual choking – and that’s entirely your prerogative – we say it’s a good idea to make it something you only practice occasionally, rather than part of your ‘daily’ or regular sexual practices,” Ms McMillan said, referring to Women’s Health NSW’s online learning hub, It Left No Marks.

Though the program stresses that there is no risk-free way to engage in the act, it provides information for people “about lower-risk activities, including holding your own breath (so you can let it go when it gets scary) and simulating choking (play acting) rather than actually restricting someone’s air or blood flow to the brain”, Ms McMillan said.

“Nobody wants to give or receive a brain injury during sex,” she added.

Given the threat to people’s brains posed by strangulation, Prof Douglas said that “we need to separate (it) from other kinks”.

“Helping people to understand these risks is key,” she said.

Originally published as ‘From fun to deadly very quickly’: Dangerous bedroom act on the rise in Australia