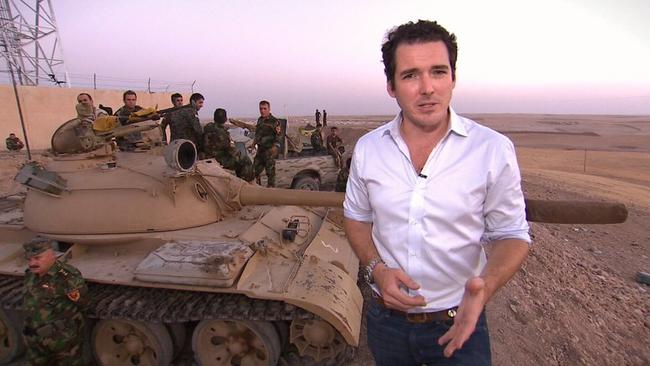

Peter Stefanovic book extract: ‘The most confronting and disturbing day of my life’

AS A foreign correspondent, Peter Stefanovic travelled to the world’s most dangerous places. But as he says in this book extract, one day really stands out.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ON July 17, 2014, most of Australia was asleep when news broke about a missing plane in eastern Ukraine.

Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 had disappeared somewhere east of the country’s second city, Donetsk, where I’d already spent several weeks that year reporting on a civil war that was raging between the Ukrainian military and Russian-backed separatists.

I watched the news unfold on Twitter and various news wires from my hotel desk in Gaza where we’d been reporting on rising tensions with Israel. Planes don’t just go missing, so we assumed it had crashed. Also, the passenger liner was on its way to Kuala Lumpur from Amsterdam and so it was highly likely Australians would be on board.

Cameraman Luke Wilson and I started packing our bags in preparation to fly to Donetsk, but as we were preparing to walk out of the hotel doors, the Israeli Defence Force made a stunning announcement — it was invading Gaza.

This was also very big news but the decision about which story to cover was taken out of my hands. The border between Gaza and Israel was now closed and wouldn’t be reopened for days, if not weeks. Luke and I were stuck in Gaza, and in for the long haul.

I felt torn. I wanted to cover the plane crash because I knew the region and its players so well, but I also wanted to stay in Gaza for the same reason.

But ultimately, reporting on conflict is my preference. It also irritates me when I can’t see a story through. The adrenaline rush that comes with war reporting can be quite addictive. (Winston Churchill once said that nothing in life is as exhilarating as being shot at without a result. I can certainly relate to that after two bullets narrowly missed me while reporting in Libya in 2011.)

I never took unnecessary risks — and of course the story was never about me — but I always felt a certain excitement whenever I stepped into a theatre of war.

The night following Israel’s announcement was bloody and brutal, and all I heard was the long, sustained volley of rockets that launched and exploded minute after minute.

The next morning, I received a frantic phone call from our fixer in Gaza, Ameera. Almost breathless, she said, “Peter, it’s been a very bad night. I haven’t slept at all. The Israelis were bombing and bombing and bombing. There is a suburb called Shejaia in the east that has been destroyed. There are dozens of dead bodies still lying on the street. People were killed as they ran away from their homes. It’s a massacre. I need to go home and be with my children so I am sending a friend of mine to drive you around today. His name is Omar and he will look after you. It’s okay, you can trust him.”

What was to come was, quite simply, the most confronting and disturbing day of my life.

Omar picked us up and drove us to the main al-Shifa hospital, which was completely overwhelmed.

Outside the ER, ambulance after ambulance pulled up and dropped off the dead and wounded. Most of the people had suffered horrendous injuries, such as missing limbs, broken bones, severe cuts and wounds. It was a very hot day and doctors were pushing and yelling at one another out of frustration. They were doing their best to maintain control in an environment where it could so easily have slipped away.

Resources were absolutely stretched because medical supplies were already low. It was a desperate case of providing attention and resources to only those who could be saved.

I walked around the back of the hospital to see how the morgue was coping. I saw utes pull up and dump dead bodies. Mothers were crying, brothers were wailing, it was an awfully sad sight. It’s religious custom for those of the Muslim faith to be buried on the same day of their death and family members were doing their best to make sure that was happening.

The bodies were loaded into freezers until they could be identified. Then they were wrapped in a white blanket, picked up, and taken to a funeral.

But it was a day of extraordinary circumstance. There was hardly any more room inside the morgue, so bodies were left in the open. Piles of dead children lay on the bloodstained floor.

The damage was so severe that we heard a ceasefire had been agreed between Israeli and Palestinian authorities. A temporary two-hour break in fighting to allow paramedics to get into Shejaia and pick up the dead bodies or rescue any remaining survivors.

I agreed with Luke and Omar that we would go and at least check out things in Shejaia.

Jackets and helmets on. It was a fifteen-minute drive to the densely packed eastern suburbs of Gaza, which had been completely destroyed by war.

The streets were flattened and huge columns of black smoke rose from several areas.

Paramedics were rushing from house to house pulling dead bodies out from underneath the rubble.

I walked past dozens of bodies. One elderly lady, whose clamped hands dangled off the stretcher, had died with a look of fear in her eyes. Half-a-dozen drones circled the sky above. A swarm of them buzzing away.

Luke filmed as fast as he could to try and capture the madness and devastation. Burnt shells of cars, crushed homes and mosques, collapsed trees and powerlines on the ground. It was apocalyptic.

I felt incredibly uneasy, so after about 15 minutes we sped out of there. Not even 10 minutes after we escaped, the ceasefire collapsed, and the death toll continued to climb.

The arithmetic of death was about 20:1 — 20 dead Palestinians to one Israeli.

But civilians in Gaza made up about 75 per cent of the victims. That was a staggering amount. It’s no wonder rage bubbled to the surface.

***

It’s always nice to get fan mail, and these were some of the lovely notes I received while reporting in Gaza during the fifty-day war in 2014.

You son of a bitch.

Let’s hope Hamas hunts you down.

You are a cretin.

Next time the rocket will land on you, hopefully.

You will end up being dragged around the streets tied to a motorbike until you die.

You may not survive.

The messages were delivered to me via Twitter, after I’d observed that a rocket had been fired from a compound across the road from my hotel and was on its way to Israel.

It wasn’t an aggressive post, it was just something that I witnessed, and in the interests of balance I perhaps naively reported it.

The threats continued for hours.

Someone giving deadly information to enemy while a guest of Gaza is not a journalist but a spy. Spies get shot.

Filthy Zionist pet dog.

Kick this man out of Gaza.

The irony was that I’d been in Gaza for weeks and had covered the lopsided scale of Palestinian death and destruction caused by Israel’s military might.

In any case, I got the message. I’d never received any death threats before, and when someone says you should die, you tend to take notice.

I took the messages seriously, and began to feel as though Luke and I might be even less safe than we already were.

We had been working 24-hour days in a heated and violent atmosphere. Without proper sleep and rest, my mind began to play tricks on me.

One evening I was on the balcony of the hotel, in between live crosses to Channel Nine, when I thought I saw a missile heading right for Luke and me. I fell to the ground and raised my voice as if to say Look out!

Nothing happened.

Luke looked at me and laughed. The missile I’d seen was a white bird flapping its wings as it gracefully flew through the air from the ocean to the hotel.

I shook my head. I was going bonkers.

Luke continued to laugh, and then I laughed too. But Luke also told me he knew exactly what I thought and felt because the same thing had happened to him a day or two earlier.

It was definitely time to go. It might seem like it would be a great joy or relief to leave dangerous, war-torn places, but it’s actually not such an easy thing to do. I would not be human if I didn’t feel the fear that people experienced, the desperation of living in extraordinarily difficult and dangerous environments, the struggle of sourcing clean water and food, or finding an hour of peaceful sleep.

So when I say goodbye to new friends like our fixer Ameera who have put themselves in harm’s way to keep me alive, it’s hard to just drop it all at the airport.

I can leave, they cannot. I live in a country where I am free to do and say what I like, when I like, but they aren’t.

For example, all Ameera’s husband wanted to do was visit Jerusalem and pray, but he couldn’t even do that.

I left Gaza and Israel with a heavy heart, while the local people stayed behind and picked up the pieces, knowing it was highly likely war would resume again, probably in the not-too-distant future.

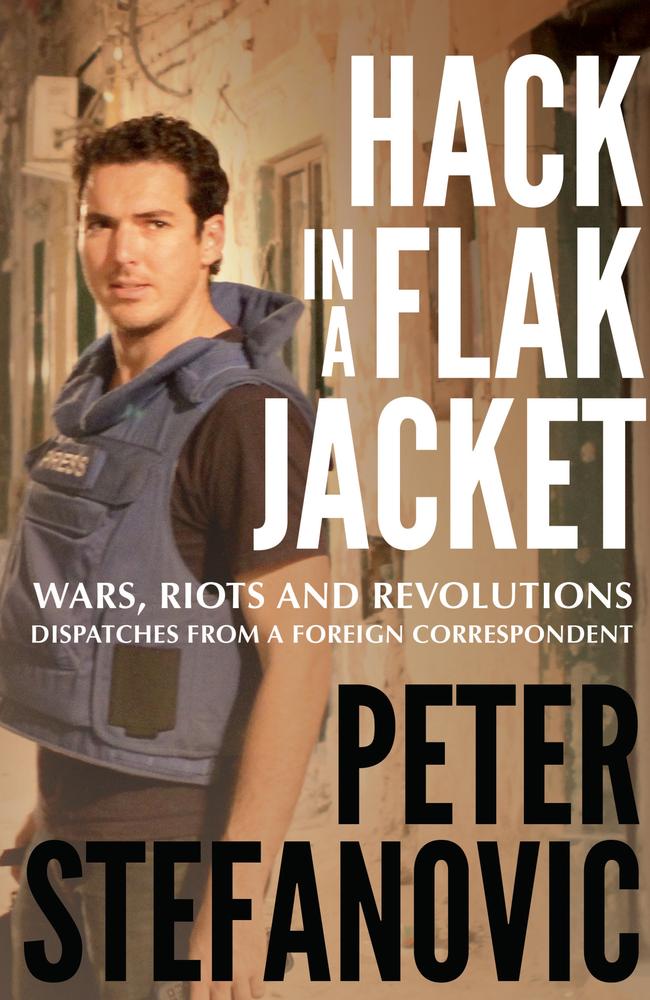

This is an edited extract from Hack in a Flak Jacket by Peter Stefanovic, published by Hachette Australia on 9 August, RRP $29.99.

Originally published as Peter Stefanovic book extract: ‘The most confronting and disturbing day of my life’