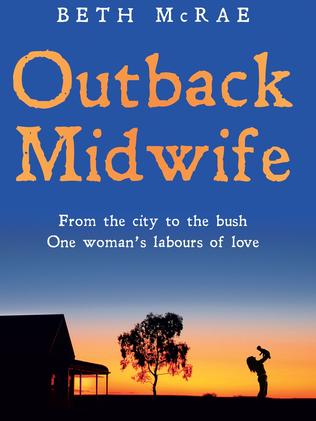

Outback Midwife book: The ridiculous way newborns used to be treated

BIRTH is no delicate matter and the things midwives see would astound you. But as Beth McRae can attest, not very long ago things were done very, very differently.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BIRTH is no delicate matter, and over the years midwives accumulate an array of astounding, terrifying and heart warming stories.

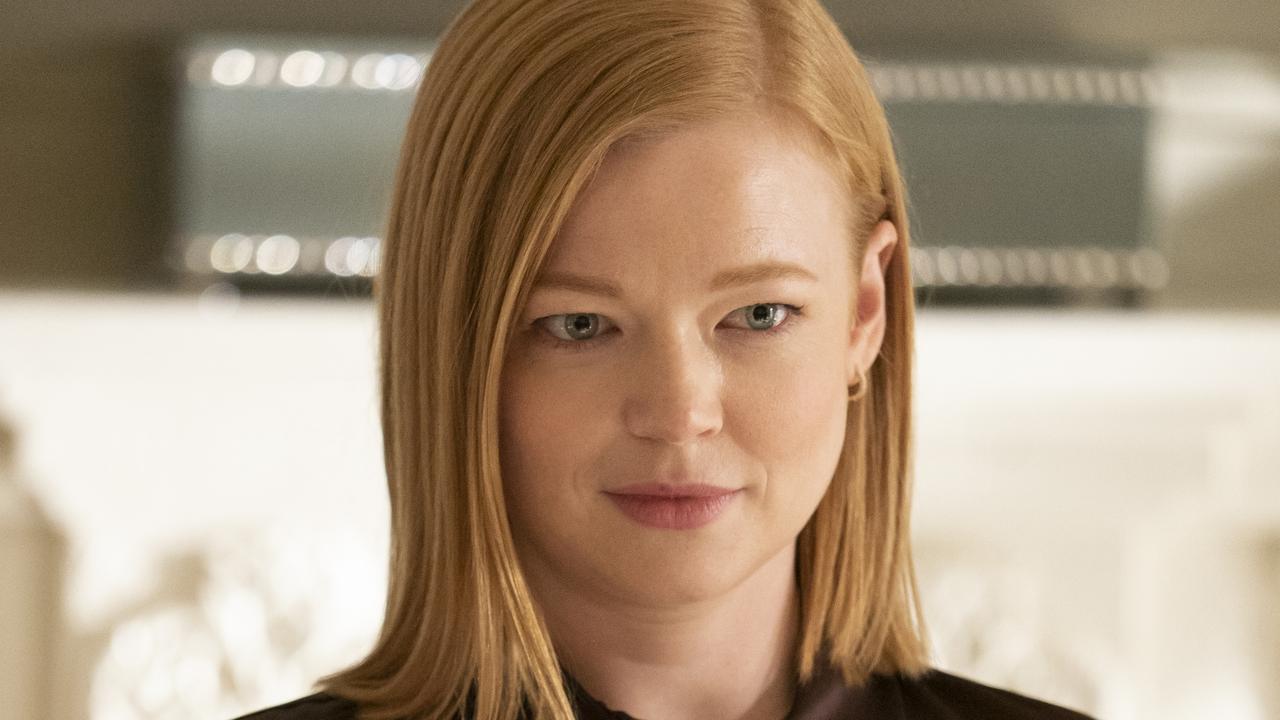

Beth McRae spent 40 years as a midwife

And for any woman who has ever gone through the pain and joy of having children, her story is an eye-opener.

Her story, Outback Midwife is about her personal journey from the bush to the city and back again. Right now she’s working in a remote indigenous community, but back when she started midwifery in Melbourne things were done very, very differently. The stories of how babies were born and cared for just a few short decades ago will amaze you.

News.com.au has been given an exclusive first extract from the book.

Read on.

***

A BIRTH didn’t count on my record unless I’d attended to the end, which meant delivering the placenta as well. One day, as I oversaw this third stage of labour, pulling gently on the mother’s umbilical cord I was alarmed to feel a sensation that didn’t seem quite right.

‘I think I felt it tear,’ I whispered to my mentor Julie.

‘Just leave it for a couple of minutes then start again,’ she said.

Once I felt that the mother’s uterus was still contracted like a cricket ball, I reapplied gentle pressure to her belly and I pulled the cord. Almost immediately it severed and sprang away — minus the placenta. Horrified, I turned to Julie.

‘Don’t panic,’ she said. ‘It still might come on its own. We need to wait a little longer.’

Although she seemed calm, I felt far from reassured. When the placenta fails to detach, or partially separates from the uterus, the uterus can’t contract properly, and this can lead to severe blood loss, or a post-partum haemorrhage (PPH), as it is usually called. What if my patient started bleeding?

Twenty minutes later there was no sign of the placenta delivering spontaneously, and I had the unenviable task of informing my patient she would now need surgery.

Thankfully, it took no time for arrangements to be made to transfer her to theatre so the obstetrician could remove the placenta under a general anaesthetic. This worked out fine, but that didn’t stop me feeling awful, and embarrassed. It definitely galvanised me to hone my technique. With experience I learnt to identify by feel the sensation that alerts you to when the cord is about to tear, and to stop pulling.

At some point in their career, a midwife will have to deal with a post-partum haemorrhage, and as it turned out it wasn’t long after this that I experienced my first. I was on night duty and in the early hours I answered the bedside bell of a first-time mum, Alice, who had come from the delivery suite earlier that evening.

‘I think I’m bleeding,’ she told me.

Pulling back the blankets, I switched on my torch and shone the beam down the bed. There was a pool of blood oozing from between Alice’s legs. I rang the bell three times to alert my colleagues, but when I peered down the ward there was no sign of anyone. I realised with dismay they must still be feeding the babies in the nursery.

‘I’ll be back in one minute,’ I said to Alice. ‘I just need to get something.’

The nursery was a good 20-metre walk from the ward and as soon as I was out of Alice’s sight I began to run.

‘You need to come quick,’ I panted as I burst in there, startling Julie, the senior midwife on duty that night. ‘I have a woman bleeding and I need help. Can you phone the registrar then come to room six while I go back to her?’

I ran back to Alice and wedged cotton pads between her legs. By now the sheets were drenched and the blood was pooling at an alarming rate. I knew I was dealing with a post-partum haemorrhage.

‘What’s happening?’ Alice asked with panic in her voice.

‘I feel sick.’

When Julie arrived she began to rub Alice’s abdomen, trying to stimulate the uterus to contract, which would help to stop the bleeding. The doctor had been called and I’d fetched the ergometrine — medication that would hopefully help to force Alice’s uterus to contract.

We gave Alice the medicine and Julie asked me to take over kneading Alice’s stomach. Despite my best efforts I could feel her uterus relaxing rather than showing signs of contracting under my hand.

‘Stop it, it hurts!’ Alice cried out, trying to push my hand away. Now sweaty and woozy from the blood loss, she looked dangerously close to passing out. Another huge clot oozed between her legs and I felt very frightened for her. My heart was pounding in my chest but I tried to keep calm and focus on following Julie’s instructions.

‘We’ve got a PPH,’ Julie called out, spotting the resident doctor at the top of the ward. ‘We need to get this girl to theatre now.’

Quickly setting Alice up with a drip, we pulled the bed away from the wall and wheeled her to theatre. With her fate now in the hands of PANCH’s skilled obstetricians, there was nothing more we could do.

Back in the ward I had my work cut out calming some other mothers who had been awoken by the commotion and were understandably concerned. Once the lights were out again and everyone was settled, I joined my colleagues back at the nurses’ desk. My hands were still shaking and my mind was racing as I replayed what had unfolded. Had I helped Alice quickly enough? Would she be okay?

When the phone rang 45 minutes later, I braced myself for bad news, but as Julie replaced the receiver she looked relieved. ‘Alice is out of surgery now,’ she said. ‘They found a small piece of placenta, and they’ve removed it. She lost a lot of blood so they’ve given her a transfusion. Well done, Beth, for acting so quickly.’

My hands still shaking, I let out a sigh of relief.

My rotations on the night shift were not, however, usually this fraught. Mostly they entailed manning the fort from the nurses’ desk and answering the call of any mums who needed help with pain or a trip to the toilet.

Two o’clock in the morning was feeding time for the babies in the nursery and by far our busiest time. When all the cots were filled it took quite a bit of work to help the on-duty mothercraft nurse get the babies suckling on their overnight feed. It seems unbelievable now, but at PANCH in 1974, at night the babies were given boiled water rather than milk. The prevailing wisdom — which as a 22-year- old rookie I didn’t think to question — was that in order to be taught to sleep through the night, a baby should not become accustomed to feeding from the mother’s breast, or from a bottle of milk; instead, he or she should be given a small amount of water. Ideally the baby would then go back to sleep as quickly as possible. Unsurprisingly, since boiled water does not have the hunger-relieving or sleep-inducing effects of breastmilk, most would struggle to resettle. Often there would be a dreadful racket when they woke and bawled for a feed.

Although such practices were entirely the norm then, when I heard stories of midwives passing from cot to cot propping up babies’ bottles with nappies in order to allow infants to feed themselves, it struck me as a terribly dangerous thing to do. What if a baby choked?

To deal with our tiny army of insomniacs, a member of staff would sometimes sneak down to the kitchen and grab sachets of honey, which was smeared on to the babies’ dummies so that they would suckle and fall asleep. A twenty-first century mum might find the idea of these kinds of settling techniques unbelievable, but they really did happen, and of course they really did work — although I would certainly strongly recommend against them now that we are more enlightened about dental hygiene and the kinds of foods tiny babies should ingest!

***

In the maternity wing at PANCH, it was usual for new mothers to stay with us between five and seven days while they learnt to care for their babies. As a student midwife I was tasked with helping to bathe and change the newborns. I also stripped the beds and emptied the dirty linen skips, which inevitably smelt a bit ripe. Then, at four-hourly intervals, I’d oversee the breastfeeding — again following a regimented routine.

First, the mothers were ordered to wash their nipples with sterile cottonwool and water. Then, once their babies had latched on, we’d have to time the proceedings. The rule

was that a new mother should feed her baby for just three minutes on each breast. Although the amount of time on the nipple extended daily, it seemed unkind to pull a hungry baby away from his mother’s breast. But those were the rules and we had to follow them.

‘If the baby’s still hungry, give it cool, boiled water,’ I was told by Gayle, the strict charge sister. Her explanation was that limited feeding prevented the mothers from developing sore nipples. However, I suspected it was more about lessening the workload for the staff. If a mother developed cracked nipples, she or a midwife would need to express the milk from her breasts, a time-consuming, uncomfortable and labour-intensive procedure no one enjoyed.

Gayle was also a stickler for ‘compulsory nursery time’, enforced between the hours of 12.30 and 2pm and then from 10.30pm until the early morning feed at 6am. When the babies were in the nursery, their mothers were supposed to be resting. This was easier to enforce during the night than the daytime, when it was not unusual to find an anxious mum pacing the corridor, adamant she could hear her baby crying.

‘That’s not your baby,’ a poker-faced Gayle would scold, before dispatching her back to bed. Yet the majority of the time it really was. All baby wails may sound the same to midwives, but somehow a mother just knows her baby’s cry; maternal primal instinct is extraordinary.

Outback Midwife is published by Random House and this extract was reproduced with permission. RRP $34.99

For information go to www.bookworld.com.au

Originally published as Outback Midwife book: The ridiculous way newborns used to be treated