‘I’ve seen some nasty things’: Life as a prison nurse

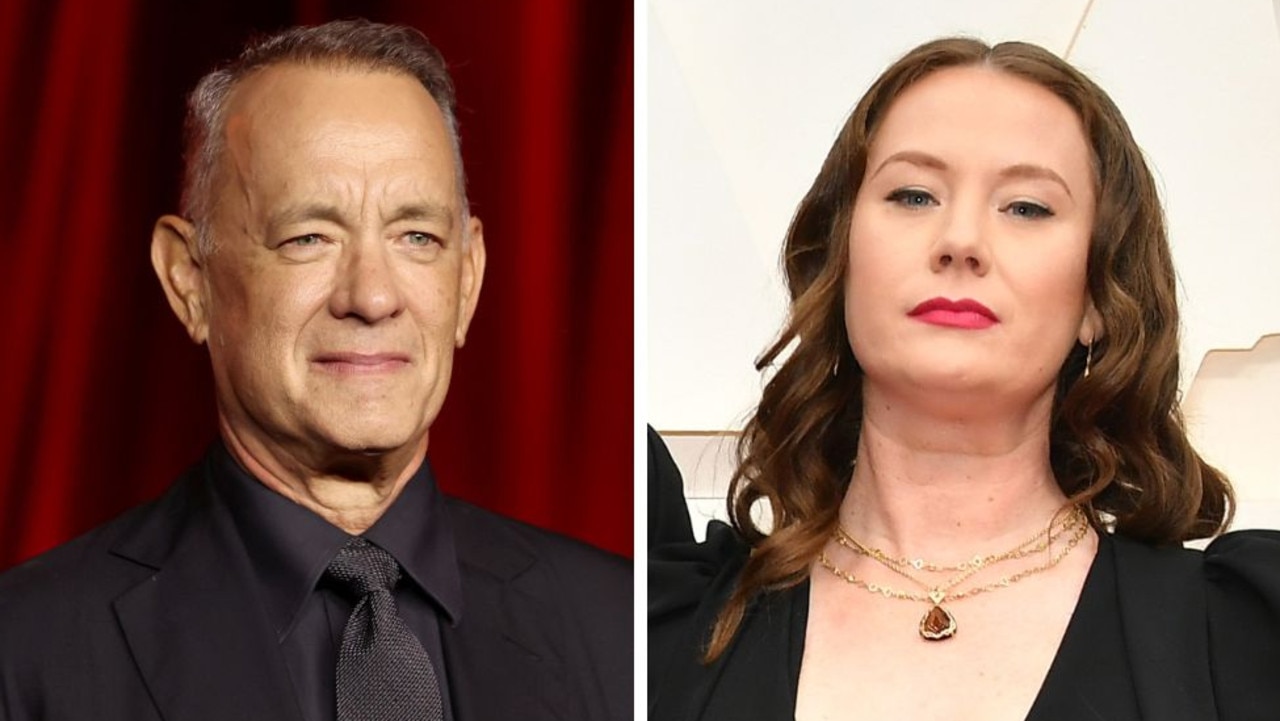

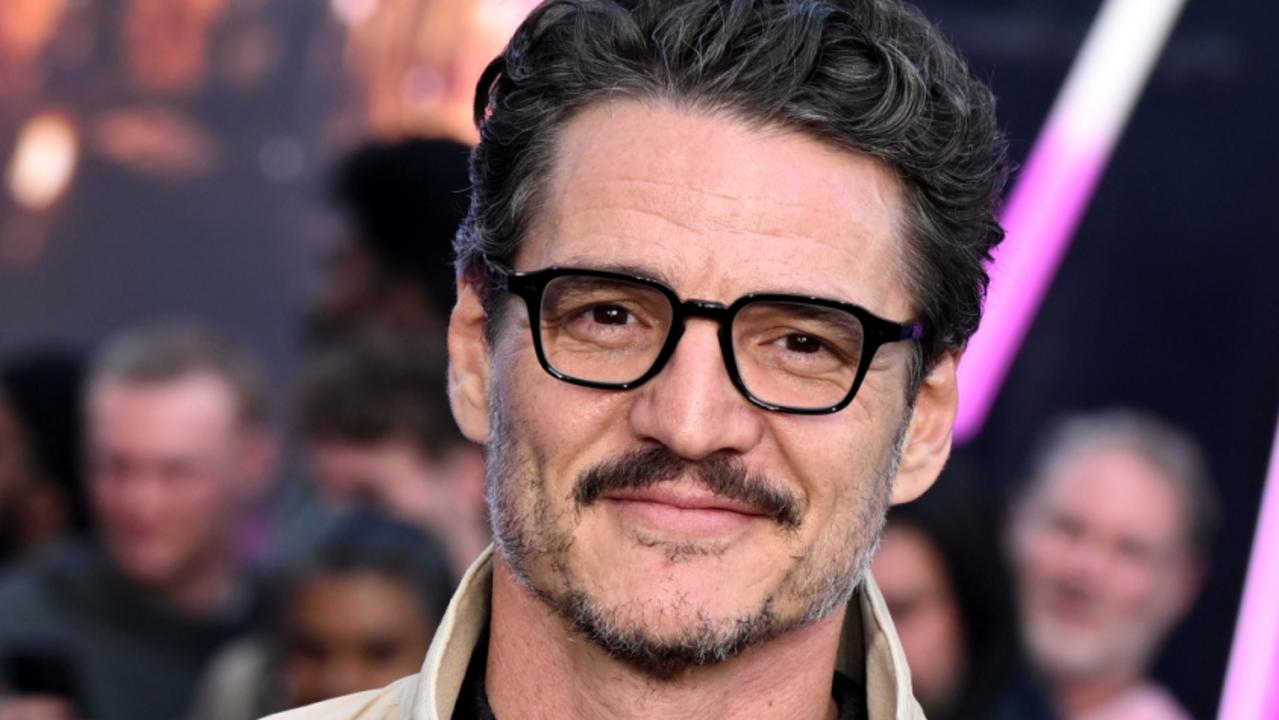

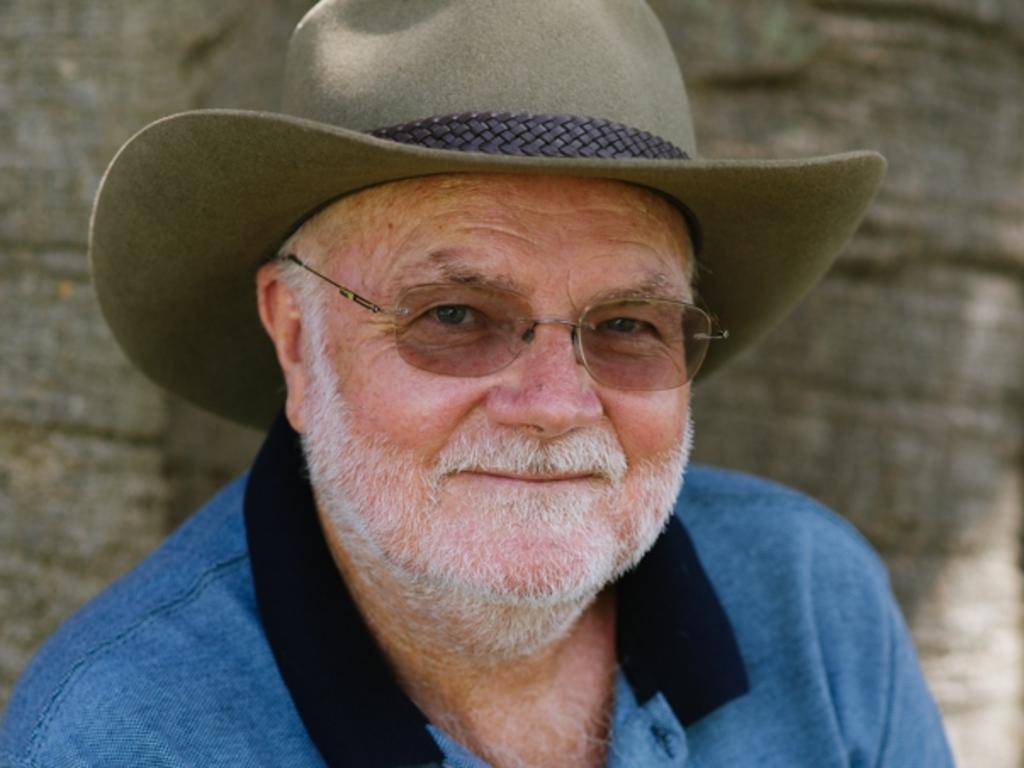

A former nurse gives Bill ‘Swampy’ Marsh a rare glimpse into prison medicine – surprisingly declaring that “as a nurse, I’ve never felt safer than I was in the prison environment”.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fascinating stories from the frontlines of Aussie law enforcement are unearthed by BILL ‘SWAMPY’ MARSH in his latest book. In this extract, a former nurse gives a glimpse into a little-known and confronting world – prison medicine.

I started out at Ashford Hospital, in emergency, which I absolutely loved, then moved over to the high dependency and intensive care units at the Memorial Hospital.

One day, when we were moving a patient, she grabbed onto me and she basically ripped my shoulder: ligament damage, bursitis and all that sort of thing. So that was that. I wasn’t able to lift people any more.

I didn’t want to be on workers’ compensation so after a male nursing friend said, ‘Hey, I’m now doing casual work at the prisons. How about you come here?’, I thought I’d give that a go.

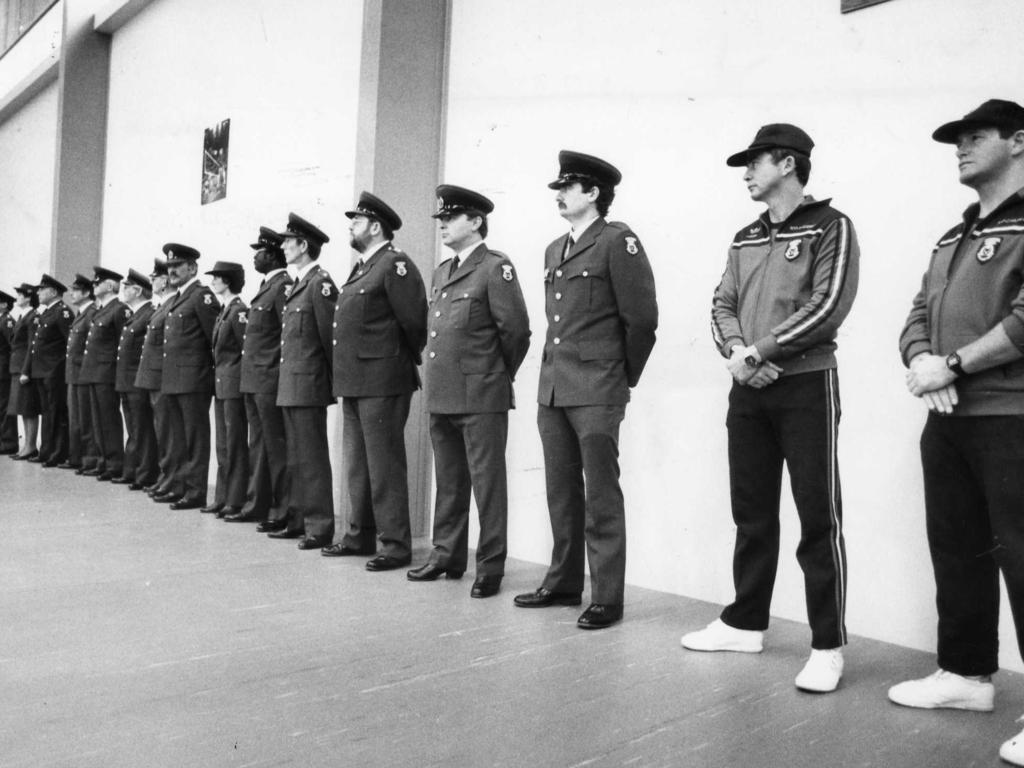

The person who interviewed me was Raylee Kinnear. Raylee was director of nursing for the South Australian Prison Health Service. She was the most amazingly wonderful woman. Raylee was responsible for around a hundred and fifty nurses, plus all the doctors, dentists, occupational therapists and psychologists, plus all the medical services and health provisions for every patient, in every prison and remand centre throughout the entire state — city and the bush. Her office was virtually a cupboard under the stairs in the main building at the old Glenside Hospital, and she had to run it all on a shoestring budget. Anyhow, I went to the interview hoping for a part-time casual position and I walked out with a full-time job at Adelaide Remand Centre.

I started out as a nurse-on-site and a year later I became nurse manager, in charge of the daily running of the remand centre. Part of my responsibilities included the prison opioid

substitution program. That’s where medications like naloxone and methadone were given to prisoners to help treat their drug addiction. Problem being, many of them would try to sell or trade the drugs with other prisoners. For example, naloxone’s a tablet that’s placed under the tongue and the prisoner’s supposed to swallow it. But they were forever trying to hide it under their tongue or in a tooth cavity so that they could sell it on. Same with methadone.

Methadone came in a pre-bottled dose to be taken with water. The thing was, they’d go back to their cell and regurgitate it through a sock or something, to take out any lumpy bits. And then they’d sell it on.

The easiest thing to get in a prison is drugs. I heard that, in one place, they had drones dropping drugs inside the prison walls. They’d also try and smuggle them inside babies’ nappies or through kissing their girlfriends. Other times their mates would load up tennis balls full of drugs and, while the prison officers were busy trying to sort out a concocted

riot at one end of the prison area, their mates would be hurling the tennis balls over the wall down the other end. So there were huge issues with drugs.

You also had to be careful not to fall for some of their stories or get too familiar with them.

The thing you have to realise is that prison’s not some sort of game because, while we get to go home, they don’t. Prison’s their life and there’s no respite from the intensity of it. So, if anyone’s seen to be favouring one prisoner over any of the others, there can be dire consequences.

It’s what’s called ‘splitting’. Most times splitting occurs between prisoner and prisoner. And under the dictates of prison justice, they’re never to tell anyone on the outside the truth about what actually happened. It just amazed me as to how many times a badly injured prisoner was brought to the infirmary and told me that they’d slipped over in the shower or they’d fallen and hit their head on a hand basin. And that’s even when I could see the footprints and fist markings all over them.

Though the group that’s most prone to prison justice is the protected prisoners. They’re the pedophiles, the rapists, the informants or those who have harmed a child or the elderly.

They have to be under full-time protection from the mainstream prisoners because, prison justice decrees, if a prisoner comes across a protected, they’re to inflict maximum injury upon them. To that end we even had to set aside a day for the protectees to be escorted to the medical centre separate from the other prisoners.

Within the prison itself, if trouble occurs, there’s different alert codes. Code Yellow means ‘officer requires assistance’. When that happens, there’s an instant lockdown and the other officers run to their officer mate’s aid. We, the medical staff, then wait for a Code Black, which is a ‘medical emergency’. A Code Black means that somebody’s been hurt or they’ve been smashed up or they’ve hanged themselves. A Code Blue is when we attend. All prison

officers are trained in first aid, which is good, because I’ve had them doing CPR — cardiopulmonary resuscitation — while I’m busy getting lines in or getting the oxygen on or attending to their injuries. And I can tell you, over my time in the prison system, I’ve seen some really nasty things; like deaths, hangings, attempted murders, lots and lots of assaults and hundreds of slash-ups.

Slash-ups are often caused by patients with mental health issues who find that self-harming makes them feel emotionally better. It’s a release, as are the attempts at hangings.

Working in the prison system was a very interesting experience. Though in saying that, as a nurse, I’ve never felt safer than I was in the prison environment. That’s because a prison officer was with you at all times. They’re there for your own protection, so you’re their total responsibility. So if anyone on the medical staff gets hurt during that time, the attending prison officer will get black-listed which, I guess, could also be described as another form of prison justice.

This is an edited extract from More Great Australian Outback Police Stories by Bill ‘Swampy’ Marsh: available now, published by ABC Books.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘I’ve seen some nasty things’: Life as a prison nurse