How Kim Jong-il kidnapped movie royalty and forced them to make his films

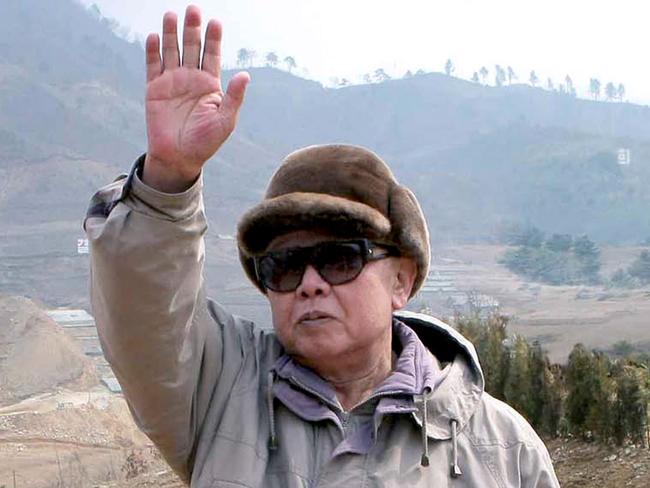

KIM Jong-un isn’t the first of his dynasty to be a movie buff. His father was so obsessed, he kidnapped a film star and her husband to realise his vision. This is their story.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN Kim Jong-un recently punished Hollywood for a movie he didn’t like, the world was gobsmacked.

But he wasn’t the first Kim with a keen interest in cinema.

His father, Kim Jong-il, was such a movie buff he kidnapped a film star and her director husband to make motion pictures especially for him.

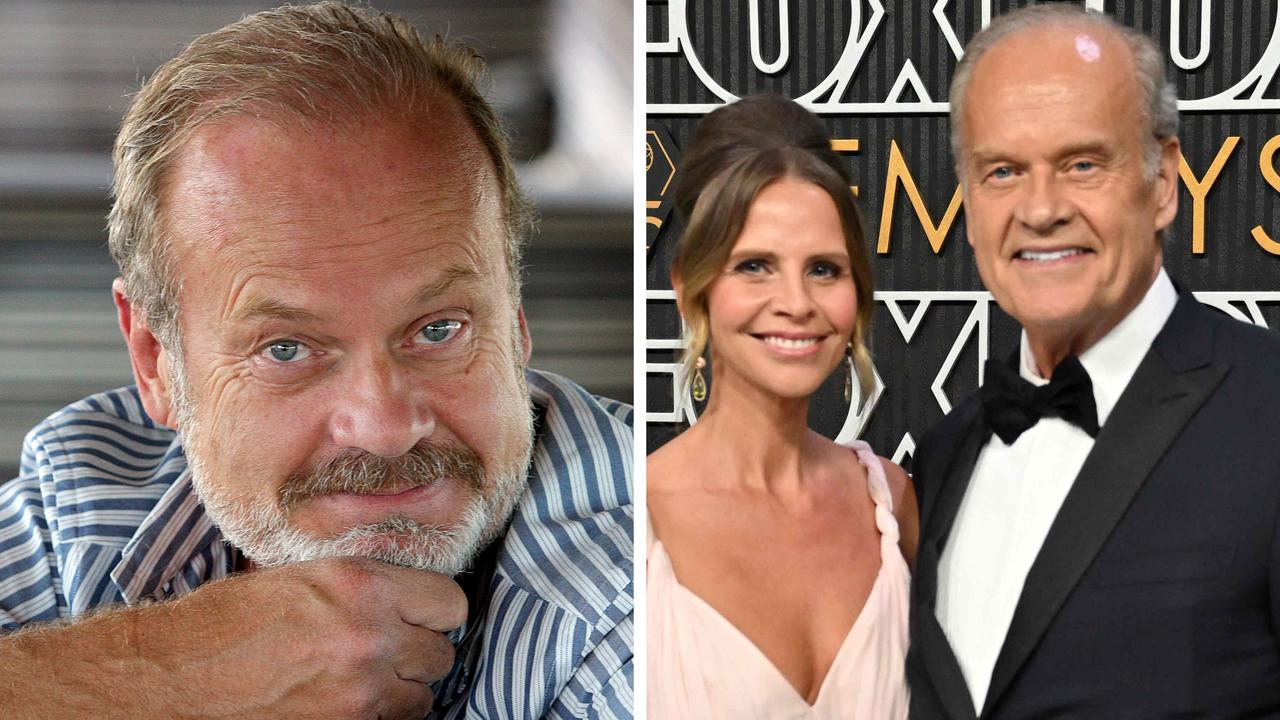

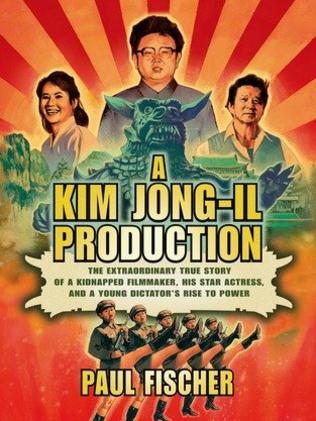

The extraordinary tale is chronicled in Paul Fischer’s new book, A Kim Jong-il Production, the true story of the obsessed dictator’s bizarre vanity project.

Fascinated with Hollywood from his youth, Kim Jong-il had “a sense of drama, of narrative and showmanship, of mythmaking and its power.”

He adored James Bond and the Friday 13th movies, as well as Japanese movies, and worshipped Sean Connery and Elizabeth Taylor. Kim learned everything he knew from the silver screen, Fischer writes.

“A lot of dictators in 20-century history have had a strong affinity with film and its almost hypnotic power,” Fischer told news.com.au. “That was true of Kim but I also think he saw himself as an artist, dreamt of himself as a filmmaker, and genuinely had a passion for the art form, which maybe was born when he was an over-privileged, isolated child for whom films were both escapism and his only window into the outside world.

“He used his father’s embassies to set up a worldwide bootlegging network through which he copied and collected every new release the world over, building a private archive that counted thousands and thousands of titles, all reserved for his exclusive viewing.”

His father, “The Great Leader” Kim Il-sung, did not share his son’s addiction, but he recognised the value of a good story.

Kim Jong-il was installed as head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department, and director of its Movies and Arts Division. But he became disillusioned with North Korea’s film industry, finding their work “increasingly repetitive and dispiriting”.

By the late 1970s, he was effectively acting as the country’s leader — and he was used to getting what he wanted. He had already carried out numerous kidnapping of citizens from countries around the world, forcing them to teach his spies how to infiltrate their countries.

Now, he alighted upon the idea to kidnap two of South Korean cinema’s most famous names to assist him in making the world sit up and take notice of the People’s Democratic Republic.

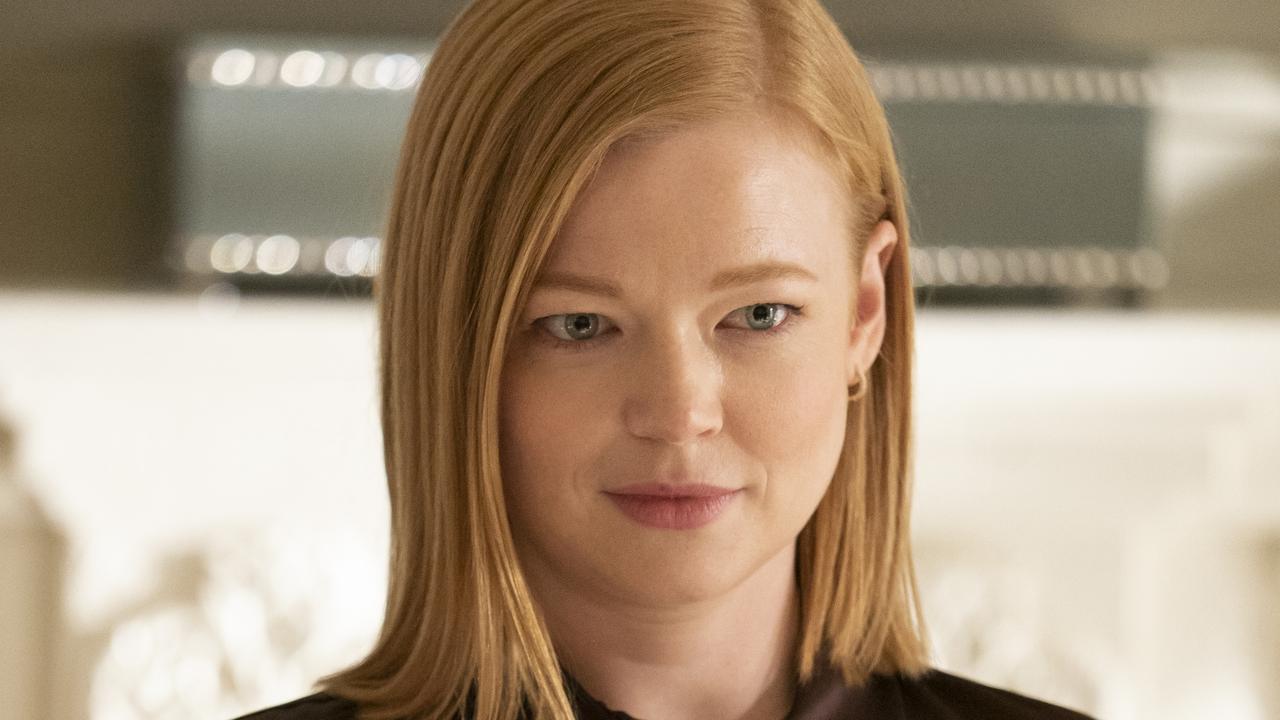

Choi Eun-hee, or Madam Choi, had starting making a name for herself before the end of the Pacific War, when Korea was still one country. She had worked as a stage entertainer for both sides during the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. She had then gone on to leave her respected, cameraman husband for young, talented director Shin Sang-ok.

Together, they had become the elegant power couple of the South Korean movie industry.

But Kim Jong-il had a plan. Choi Eun-hee was invited to Hong Kong to meet a film producer. When she arrived, she was taken captive on a boat and told she was “going to the bosom of General Kim Il-sung”.

Shin Sang-ok was separated from his wife at the time, but he rushed to Hong Kong as soon as he heard she had vanished. But police believed he was responsible for her disappearance.

The panicked director agreed to meet a mysterious man by the docks to buy a fake passport, and was promptly captured and put on the second boat to North Korea.

The couple were put under house arrest in separate luxurious villas, but after Shin Sang-ok tried twice to escape, he was sent to prison, tortured and almost starved “to break his will”. It was five years before they were reunited at a lavish Pyongyang banquet, and it was time to execute Kim Jong-il’s devious masterplan.

The dictator gave his hostages almost $4 million and granted all their requests. They made seven movies in the following years, at first sticking to the reverent style that had defined the state-run studios, but gradually becoming more creative, with the best of North Korea’s actors, crews and production teams at their disposal.

“In one episode Shin marvelled at for the rest of his life, he needed a model train to blow up for the climax of one film,” says Fischer. “When he asked Kim for a special effects crew and a miniature train, Kim instead sent him a real, full-size train, filled to the rim with explosives.

“If they needed wind machines, Kim sent them helicopters. If a scene called for snow, Kim flew the whole crew up to the mountains. He never said no.”

Shin and Choi couldn’t directly contradict the propaganda upon which the DPRK’s cult of personality was built, but they managed to make a wide variety of pictures — 1986’s lighthearted romantic melodrama Love, Love, My Love, social-realist tragedy Salt and extravagant fantasy musical The Tale of Shim Chong.

“The films all had elements of propaganda, but also subtly subverted it,” says Fischer. “They were the first films to feature scenes shot abroad, for instance, revealing the outside world to North Koreans who had been kept hermetically removed from it for decades at that point.”

Love, Love My Love represented the first time romance had been portrayed on a North Korean screen, and Hong Kil-dong was the country’s first martial arts action film.

“Every one of the pictures broke with tradition,” wrote Fischer.

Shin’s Godzilla rip-off Pulgasari: The Iron-Eater was “the worst film he had ever made”, added the author, but Kim Jong-il loved it. His ego inflated, he agreed that the couple should open an office in politically neutral Vienna, to produce and export North Korean movies to the world.

He instructed them to tell the world that they had found “real freedom of expression” in North Korea. “I think that would sound natural,” he said. “Well, better than saying you were forcefully dragged here.”

It was the couple’s chance to escape. They evaded their minders and jumped in a taxi to the US embassy, from where they were taken to America and spent months telling the US government everything they knew about the movie-mad dictator.

The couple remained together until Shin’s death in 2006, eventually clearing themselves of the lingering suspicion in Seoul that they had voluntarily defected.

As for Kim Jong-il, his passion for cinema seemed to have been dampened.

“Shin made the most sophisticated and entertaining films North Korean audiences had ever seen, and he won a handful of awards abroad, even gaining commercial distribution in Japan or the Eastern bloc,” said Fischer. “That was a level of success unprecedented for North Korean cinema. But when Shin and Choi escaped, Kim reverted to churning out the predictable, maudlin, repetitive propaganda his studios limited themselves to before the kidnapping.”

When Kim Jong-il was immortalised in 2004’s Team America: World Police, the disgruntled leader called for the film to be banned (although not going to the lengths that his son appeared to think reasonable 10 years later).

North Korea claims its Pyongyang studios continue to make 60 movies a year. Having been inside, Fischer is convinced they haven’t made one since Shin and Choi’s escape.

Originally published as How Kim Jong-il kidnapped movie royalty and forced them to make his films