Candice Warner reveals what really happened inside the two most confronting incidents of her life

Candice Warner reveals her unimpressive first encounter with cricket ace husband David and how that turned into a love story by wooing each other from opposite sides of the globe.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

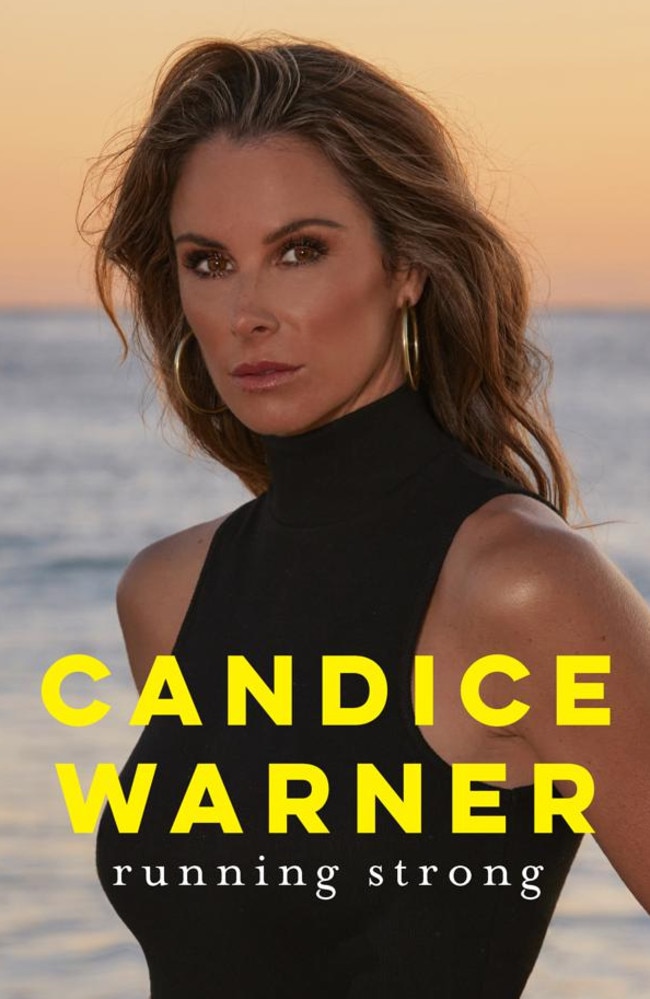

From champion Ironwoman to mother, cricket wife and media personality: CANDICE WARNER’s life has swung from extraordinary highs to heartbreaking lows, all in the public eye. For the first time, she truly lifts the lid on these moments – some well-known, others less so – and shares how she learned to keep going in her memoir, Running Strong. This exclusive edited extract is the first glimpse inside.

PROLOGUE: SOUTH AFRICA TO SYDNEY

It felt like the whole country was waiting for us at Sydney Airport. Every person in every city in every state, who all wanted to come and get a piece of the biggest news story around.

Yelling, questions, flashes and clicks. There was nothing to do but put our heads down and keep going. I’d learned that. I had one of our girls in my arms. Dave had the other. We’d just flown from South Africa to Dubai, Dubai to Sydney, and we were exhausted.

There were policemen around us, and also ill-will. I felt like a criminal, returning for justice to be served. Dave stopped and spoke briefly to the cameras. He was hurting. I could hear it in his voice, and that hurt me deeply.

It’s all my fault. I heard that in my head. It’s all my fault.

I’d been at the centre of a media firestorm that had begun eleven years before: a night out that became a conversation the entire country wanted to have. I was a kid having a pash with a boy at the pub, but the newspapers called it a toilet tryst. They put sex in the story – never explicitly, because they couldn’t prove something that didn’t happen, but it was between and behind the words that they used. Sex, technology and misogyny.

That story was a fire that raged longer than anyone would have expected, but it died eventually. Back then, I put my head down and pushed forward. I didn’t seem to be burned, but these things affect you, inside. Parts of you become raw and others become hardened. Some ideas fester.

I hadn’t told anyone, but throughout the nightmare tour of South Africa, as that country’s players and fans and officials tried to use my past to pierce through Dave’s armour, I felt that somehow I was to blame. I pushed that idea down though. It was an idea that didn’t need to be named or spoken out loud. Success would come, the tour would end. The old wounds would heal again.

They didn’t, though.

IN THE BEGINNING: BEACH BABY

It was a Sunday morning. I was six, and Dad and I were up early to walk on Sydney’s Maroubra beach. There I saw a group of kids my age having the time of their lives, running and wading and jumping in a jumble of semi-organised fun: Nippers. My eyes were saucers. It looked like so much fun. I told Dad I wanted to join in.

My experience of that first year was one big ball of laughter and competition and running. It was there at Nippers that I found that I loved running. Even as a six-year-old, it made sense to me: the mechanics of it, the feeling, the glorious exertion.

I was good at it, too. At that age, everything you do at Nippers is based around running – when you’re that young you don’t really swim or board; you mostly just run around, sometimes on the sand, sometimes through the water in wading races.

I loved running, I loved wading and I loved winning, even at that age. There was something transcendent about it. It made me more than what I had been before I’d raced. It was Dad’s smile. It made me feel good. I liked to win.

I AM IRONWOMAN

I had my Ironwoman dream almost immediately from the moment I started high school – and it surpassed all other aspirations.

My goal was qualification and I knew the best way to achieve it was simply by hard work. I trained incredibly hard, and have strong, happy memories of finishing board training exhausted but exhilarated, blood and seawater beading down my shins.

At the trials, I crossed the line in fourth place. I was fourteen years of age and I had easily qualified for the professional Ironwoman series. That made me the youngest female competitor at the time ever to do so.

I couldn’t quite believe it. I was so happy, but back then I didn’t completely understand what this qualification meant. It was an invitation to more work and not yet really an outcome. I would do the work, but while I was gaining skills, fitness and strength, I was missing out on time as a child and as a schoolgirl.

I was going to be an Ironwoman when I wasn’t even yet a woman.

RUNNING FOR MY LIFE

At nineteen, I pivoted to focus on swimming alone: my goal was the Olympics. I trained hard, but it left no time for anything else beyond my job in real estate.

One day I broke. I was overwhelmed. Was it depression? Sadness? Anxiety? I didn’t know, but I knew I was deep within it.

I visited a counsellor with some trepidation. She found that inside of me there was a lack of deep, personal satisfaction and, regardless of what I did and what I was achieving, I wouldn’t be able to find fulfilment without first addressing that lack.

She suggested that the reason I was having these feelings was because I was at an athletic nadir. For the last five years, I’d been known as an Ironwoman. My most notable achievement had happened when I was barely a teenager and now, as a young adult, I felt as though I was nothing. Just another swimmer at just another meet.

She recognised that perhaps I would never be satisfied, regardless of what I did, unless I was achieving for the right reasons. After a number of sessions, she prescribed something that seemed completely counterintuitive to someone who appeared to be burning out from athletic training.

She suggested that I start running. I was to do it for myself, though – not as a goal-oriented training tool.

Running replaced swimming, and it changed my life. It was such a different way of exercising for me. The joy was there, but the pressure was gone. Running was a happy emptiness. It was white space in a cluttered mind.

Running helped me immeasurably through this period and it has helped me through so many others since. It’s one of the best coping mechanisms I have ever found and looking back now, I think it may have even saved my life when I ended up at the centre of a vicious and confusing media firestorm that took me completely unawares.

NOBODY ASKED: THE CLOVELLY INCIDENT

The first I knew that something was happening was on Sunday; the day after the incident at the Clovelly Hotel. My agent called to tell me two things. The first was that a photograph of me kissing NRL player Sonny Bill Williams was being circulated around the country via text message and email, and the second was that a newspaper was going to publish a story about it the next day.

I didn’t think there was anything to this story, but I didn’t get to decide. I was horrified, and a thousand questions flooded my mind. The two that loomed largest were why any newspaper would want to publish a story about Sonny Bill and me kissing, and how they and other people could legally share a photo of me in a bathroom. Soon those questions gave way to another: how the hell were my family going to handle the story?

I didn’t tell my parents what was coming. I didn’t tell anyone. I hoped it was going to be a tiny little thing, secreted away deep in the folds of the newspapers.

None of that hope was realised. Not only was the story prominently displayed alongside actual news, the photograph had been published, which had been shot up and under my skirt inside the bathroom. The story also suggested that Sonny Bill and I were having sex in the bathroom, even though those words weren’t used. That would be a plain reading of the story, and was the conclusion that most readers came to.

‘Toilet tryst’ the newspaper said. That would be a euphemism that I would become disgustingly familiar with.

I felt sick to my stomach. I couldn’t keep it all in my head at any one time. It was too big. I could only think about parts of it, like how it would affect my parents and brothers, or how it would affect me in surf competitions, or how it may affect me as I walked down the street. If ever I managed to reconcile one aspect, another would emerge from the murkiness and sit there, ugly and dark in my consciousness. There was no respite.

I kept telling myself that I just had to keep going, push through. The story had come, and it would go, like all news stories. After all, how interesting was this story, really? Surf lifesaver pashes footy player in local pub?

The next day, Monday, was a lurching nightmare. I woke up and the story had grown legs. Every radio station was talking about Sonny Bill and me, and it was on the telly too. It seemed everyone had been invited to give their thoughts.

Toilet. Tryst. Photograph. Toilet. Tryst. Photograph.

Those words were everywhere. And so was my name. Sonny Bill was being mentioned too, but he wasn’t copping it like I was. There seemed to be a strong feeling that Sonny Bill had just done what blokes do, even when they have girlfriends, but that I was a slut. Only some people used that word, but it was always hanging in the air. I didn’t have sex in a toilet. I kissed a boy I liked. That was all.

One thing that amazed me about that period was that while everyone had something to say behind my back, almost nobody approached me about that night, and not one person asked me what had actually happened.

I think it’s because people didn’t really want to know. They had their own titillating version of events and inserting a real person and some less than titillating facts into their narrative would spoil all the fun.

HITTING THE PEAK

The journey to success is a strange one. After what felt like a very slow journey on an unpredictable route, success seemed to just happen, very quickly.

The next Ironwoman event was in February 2012, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, and I arrived there with a lightness I’d never experienced when arriving at a competition beach. I had no nerves at all. I was just walking on air; open, ready and calm.

I lined up with only the race in my mind. I felt nothing when it started – I felt nothing and I thought nothing. I just flew. It’s a transcendent feeling, and something I’ve heard other athletes describe as ‘flow state’ – when everything just happens.

I came into the beach on my ski in fifth place, and was bolstered by that. The ski was still my weakest discipline and I knew I would move past at least some other competitors as the race progressed to the other legs. And that’s what happened.

I powered through the run to the swim, then powered through the swim. As I sprinted to my board, I was in first place. I’d never led a professional Ironwoman event before! I could imagine even a year earlier, it would have been an overwhelming and depleting experience. Not now. I’d flowed to the front and there I stayed.

This was like running: the running I’d done for me – the running I’d done to find myself, be myself. I turned the buoys in the lead and led as I paddled to the beach. Only the conditions could stop me now. I only needed a wave to win.

No wave came. Nothing. Nothing. And then finally, there it was. I flowed into the beach and across the line. That’s when I came out of flow, and my emotions and feelings rushed in.

It was joy and relief, and accomplishment. It was progress. It was finality, too.

Mum and my brother Patty were there on the beach, and I shared that moment with them.

I’d won! That was something to talk about, something to think about. It was an event to attach to my name at last, an event that I owned. There was great coverage of the race. It led Sports Tonight and was on the back page of a few papers, and there were no snide comments in the text, no backhanders or smutty allusions.

RUDEST MAN I’D EVER MET

The first time I met David Warner was at the Beach Road Hotel at Bondi, having just run the 2010 City2Surf, truly one of Sydney’s great events.

I thought he was possibly the rudest man I’d ever met.

It’s a great vibe in that pub after the race, once you get over the smell of sweat and sneakers. I met my friends upstairs and we were joined by cricketer Brett Lee, someone I knew through friends of friends. I was talking to Brett about my neighbourhood, and he said I should meet a mate of his who grew up in nearby Matraville.

Dave was leaning on the bar when Brett introduced me to him. I said ‘Hello’ or ‘Nice to meet you’, and I can’t remember whether he just grunted or whether he even acknowledged me at all. I certainly didn’t see him as the future love of my life, the father of my three beautiful girls and the rock around which my entire life is now built.

***

Three years after that City2Surf, I watched a piece of branded content about cricketer David Warner playing in the Indian Premier League T20. The piece I watched had colour and fun, and at the centre of it all was one athlete, someone who I didn’t recognise at all as the recalcitrant bloke I had met at the Beach Road Hotel.

He had a funny smile, and a lovely way about him. He was reticent but also charismatic; and while it was hidden under steeliness, I could see an intelligence and strong emotional centre: a little bit of the Dave that I know and love today.

Watching that show, I got a sense that Dave and I were similar spirits.

I jumped on Twitter, planning to write about how entertained I was by the show, and wanted to tag Dave. But I found that he and I were already following each other, so I sent him a direct note instead, simply saying how much I had enjoyed watching the piece. He wrote back, and a few months later we were chatting online regularly. It all felt so easy with Dave. I’d never been so open with someone – there was no miscommunication, no artifice, no facade, just honest, real chat mixed naturally with warmth and whatever we found hilarious.

When we started messaging, David was at the beginning of a long tour of Great Britain.

Day and night we’d message, developing a bit of a routine. It was just lovely. There wasn’t anything yet that was romantic or sexual, just two people who were instantly connected: we had mutual friends from the neighbourhood; a mutual interest in the NRL; we had both recently ended relationships; we were both at the same stage of life.

Soon we started chatting over video and an even stronger connection developed. It was a special feeling, being close to someone like that, even though I’d only met him in person once – a meeting that hadn’t been successful.

Soon some little gifts arrived at the house: chocolates and little teddy bears and champagne. Dave and I talked about marriage and having kids before we’d even met properly. These weren’t serious conversations, just chats about what we both wanted in our lives. But it meant something to us both that we were so comfortable talking about it.

It didn’t take long for me to realise I was falling in love.

INSIDE THE SANDSTORM: SOUTH AFRICA

The 2018 tour of South Africa was grim: Dave’s confrontation with Quinton de Kock after personal sledging about my past; and SA fans taking the abuse to even greater depths.

Worse was to come.

I’d started to get a better understanding of the game and now knew there were some days and some sessions that were of greater importance than others. That day, I was watching one of those sessions. With one Test apiece, South Africa had pushed the lead past 100 runs with only two wickets down. The match and the series were in peril and things had become spiteful on the field.

As I sat in the hotel room with our daughters asleep, I saw, on television, a lot of chat, a lot of anger, and then something else.

I’d missed the original incident, as I’d been trying to get the girls to go down for their afternoon sleep, but a scene was being replayed over and over again. It seemed to show

Cameron Bancroft taking something from his pants then rubbing it on the ball. The commentators were making a big deal of it, replaying it over and over again and discussing it as a potential breach of the laws and ethics of the game.

I didn’t fully understand the significance of what I was watching, but at that moment I knew I had to get to the ground for Dave. When the kids woke, we all went to show our support. When we got back to the hotel, I started to understand the magnitude of what was happening.

There were a lot of meetings going on. People were scrambling, getting stories together. I didn’t see Dave much as he was drawn into a lot of those meetings, and when he wasn’t involved in those, he was distracted or on his phone.

I was just there to support him, fully and without judgment. Whatever had happened was to do with cricket, and I don’t question Dave about that. I love him, I trust him. Dave normally sleeps well during Tests – but he didn’t that night, nor for many nights afterwards.

The next day was strange. At the hotel there was an area sectioned off for players and staff and their wives and partners; and while we were all there together physically, there was a stilted pall over the room. There was little conversation, and the chat that was happening was about the fact that Dave and captain Steve Smith were to be stood down and that Tim Paine would be taking on the captaincy.

Every tour we usually have a wives and partners’ WhatsApp group so we can share information and chat, and that morning I posted a message saying that I thought we should all get down to the game, to show that we were there for the boys. I didn’t get many responses.

That morning the South Africans extended their lead past 400 and when Dave and Cam Bancroft went out to bat after lunch, the Australian side was a deflated mess. The South Africans won the Test easily. The Australian team was barely a team anymore, just a collective of shattered individuals.

Back at the hotel there were more meetings. It seemed to me that a lot of fingers were being pointed at Dave because he was someone who often managed the ball on the field, and perhaps because of people’s perceptions of Dave as someone who challenges the line.

A very rushed investigation started and some people were called to give their side of the story, but certainly not all the players and staff. Players, officials and coaches broke off into groups. There was a lot of sitting around and waiting for people to be called for interviews with Cricket Australia representatives.

I watched it all from the pool, where I was playing with the kids. So often I saw Dave there sitting, waiting on his own for his interview. It broke my heart to see that, and I wanted to run over and hug him. He was working, though, and he just had to go through his interview and accept whatever the outcome would be.

In my own way, I was going through it alone too. I didn’t talk to Dave about it as he was going through so much himself, but in some way I felt, deep down, that it was all my fault. I know it makes no sense intellectually, but my gut was telling me that if there hadn’t been a confrontation between Dave and Quinton de Kock, then there wouldn’t have been the Sonny Bill masks and songs, and if there weren’t the songs and masks, whatever had happened out there on the grounds in Newlands wouldn’t have happened either.

The team and families all flew to Johannesburg, and that leg of our travel felt as if we were going to a funeral. That night Dave received a message telling him he was to come in for a meeting with Cricket Australia chief executive James Sutherland and Pat Howard, the team’s general manager. I could tell his stress levels were sky-high.

The meeting was long and when Dave came back, he kept it together for only a few seconds before he broke down in tears. He told me he was to accept the blame for devising a ball-tampering plan, which was known about by captain Steve Smith and enacted by Cameron Bancroft.

He said he was being sent home immediately. I grabbed him and held him. He just kept apologising, over and over and over. Eventually he calmed down and I asked him what had happened in the meeting. He told me he feared that he may never play cricket again.

WHO DARES WINS: SAS AUSTRALIA

When we began filming SAS Australia, there were some familiar cast members. There were also people I hadn’t met before, such as Schapelle Corby, who was well known as a convicted drug trafficker. I was instantly judgmental when introduced to Schapelle, but as I got to know her, my attitude changed. She’s a very resilient woman, and someone with a surprisingly optimistic outlook.

I found parts of her story really resonated with me. When she’d returned to Australia from prison in Bali, she’d struggled to be out in public, worried about what people were thinking and the assumptions they were making. I’d made assumptions about her, myself, and I of all people should have known better.

I discovered from that show that my body and mind were capable of so much more than I’d realised and that felt good; and I’d also learned a big lesson about the importance of being vulnerable and opening up, too.

But honestly, the best thing I got out of being on SAS Australia was the response I received from people who watched. For me it was transformational.

The publicity was overwhelmingly positive. It seemed it had reframed people’s attitudes about me and the things they connected me with, like the Clovelly incident, or South Africa. People would stop me in the street – people I didn’t know – to tell me that they’d either underestimated or misunderstood me. It was hugely gratifying and the response gave me so much confidence – in myself, who I was, and what I was capable of.

I would do that show a hundred more times if they asked me to.

RUNNING ON: LAST WORDS

It’s strange to write a memoir when it feels like a new life is about to begin, but for a new life to start I suppose it must replace an old one.

In part I wrote this book for my girls, so that one day they’ll be able to understand the details of my story without interference or influence, and to show them that, as women, no matter how hard things get – and it does for women, in the world we live in – that they just need to keep going, keep breathing. That tough times pass, but that in order to get through those tough times you need to find something for yourself that will create a sense of safety and resilience, and to surround yourself with people who know you and who love you.

Now I’m the happiest I’ve ever been and I wouldn’t change anything for the world.

This is an edited extract from Running Strong by Candice Warner, to be published by HarperCollins on Wednesday, April 19, 2023 and available for pre-order now.

Scandal, strength and peace: Read Candice Warner’s exclusive interview with Stellar here.

Originally published as Candice Warner reveals what really happened inside the two most confronting incidents of her life