why inheritance tax would seriously backfire in Australia

An Australian economist has sounded the alarm over a proposed change to tax that could end up leaving everyone worse off.

ANALYSIS

Inequality in Australia has become an increasingly common discussion point in recent years.

While Australia is middle of the pack on income and wealth inequality among OECD countries, some propose a wealth tax or inheritance tax to reduce inequality and raise revenues.

However, new research shows the complexities of such policies, suggesting that increased tax evasion could have the unintended consequence of making everyone worse off.

Wealth inequality in Australia

The ongoing debate surrounding wealth inequality in Australia has spurred discussions about various policy interventions, including implementing a wealth tax or an inheritance tax.

For example, the Greens’ current election policy includes a 10 per cent tax on the net wealth of Australia’s 150 billionaires, while Think Forward’s survey of young Australians shows 73 per cent support an inheritance tax.

While proponents argue that such policies could generate significant revenue and reduce inequality, research by Rotberg and Steinberg, published late last year, raises important questions about the potential effectiveness and unintended consequences of such taxes.

Economic modelling and key findings

Rotberg and Steinberg developed an economy-wide model with prominent features of the US economy to analyse the effects of taxes, including wealth taxes on wealthy individuals, while considering factors like tax evasion and the complex dynamics between tax settings and savings, investment and economic output.

It incorporates realistic details about entrepreneurial activity and different household characteristics, such as labour productivity and wealth.

Their model features overlapping generations of households, who make decisions about work, savings, investment and consumption, accounting for taxes and concealing wealth offshore to avoid taxation.

The authors found that while increasing wealth taxes could significantly boost revenue and reduce inequality, given the presence of tax evasion, the reality is more complex.

Higher taxes incentivise wealthy individuals to hide their assets, leading to lower overall tax collection and a widening wealth gap.

Rotberg and Steinberg analysed the US wealth taxes proposed by Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders (two former Democratic candidates for the US Presidency).

The Warren proposal would tax wealth between $50 million and $1 billion at a rate of 2 per cent and tax wealth above $1 billion at a rate of 3 per cent, while the Sanders proposal would feature eight tax brackets, ranging from a 1 per cent tax on wealth between $32 million and $50 million to an 8 per cent tax on wealth above $10 billion.

The risk of tax evasion

By factoring in typical levels of tax evasion, they found these proposed progressive wealth taxes would cause an overall decline in economic welfare of between 0.34 per cent and 0.43 per cent.

Only when the lowest level of tax evasion is assumed (based on the lower-bound estimates of tax evasion in the Netherlands) do they find economic welfare is higher with a wealth tax. However, given the large range of tax evasion estimates in the Netherlands, this appears overly optimistic.

A wealth tax will reduce inequality, but factoring in tax evasion, everyone loses.

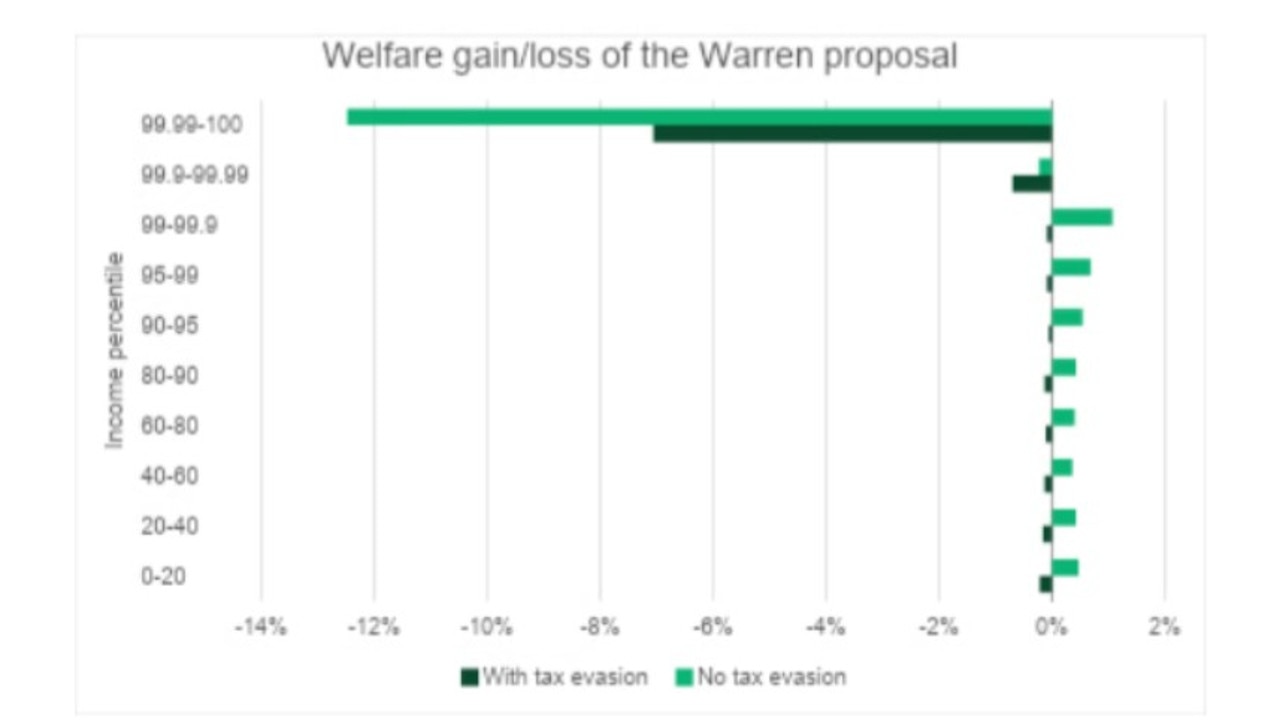

Figure 1 shows the welfare gain or loss for different income percentiles from the Warren proposal. Without tax evasion, welfare would improve for the bottom 99 per cent of households by income.

However, once realistic tax evasion assumptions are factored in, all income groups would be worse off, even after income transfers from the wealthy.

This is because, in addition to the wealthy shifting their capital offshore to avoid the tax, increased wealth taxes also negatively impact investment decisions, leading to lower economic output and lower wages for workers.

Enforcement as a mitigation strategy

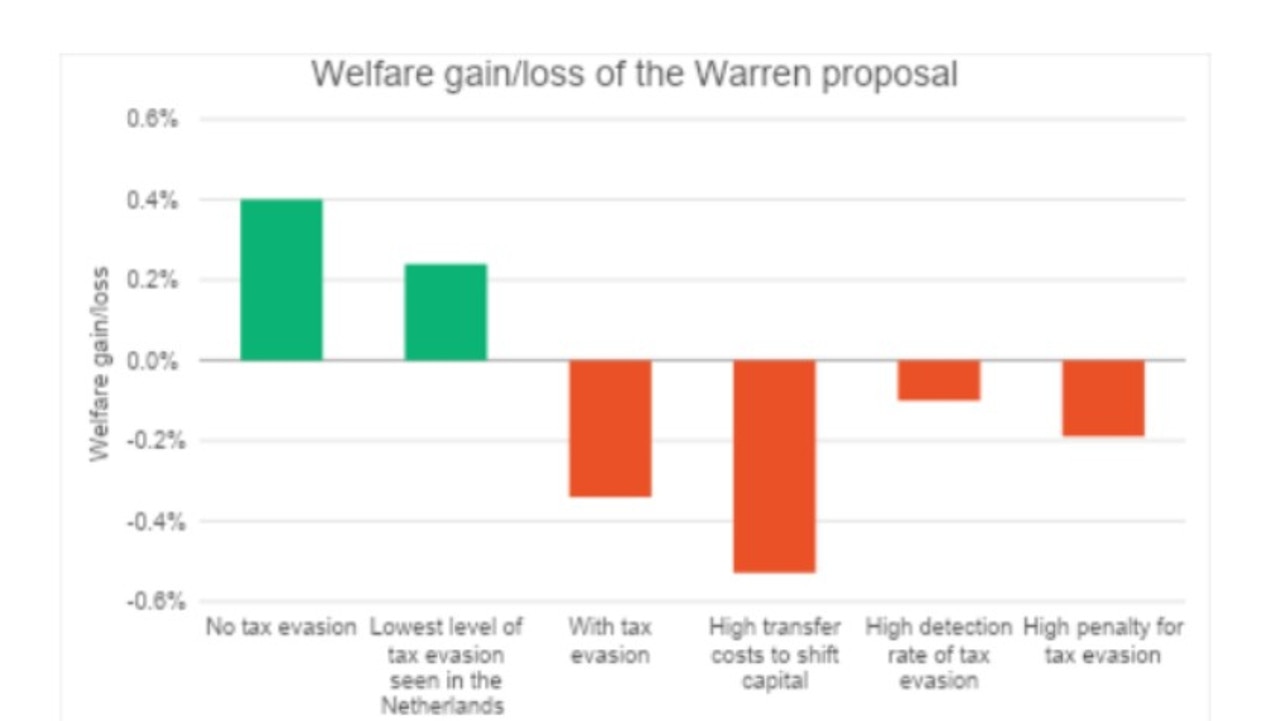

Rotberg and Steinberg also showed that increased enforcement and higher penalties can help to reduce tax evasion, but in the main, the economy is still worse off with a wealth tax.

As Allingham and Sandmo (1972) showed, there are two levers policymakers can pull to mitigate tax evasion: increasing enforcement efforts and increasing penalties.

Together, these decrease the expected returns to tax evasion.

Rotberg and Steinberg analysed what the presence of these increased detection rates and higher penalties would mean for economic welfare.

Figure 2 shows the welfare changes under alternative assumptions about tax evasion, such as higher costs to transferring money to tax havens, higher tax evasion detection rates, and a higher penalty when tax evasion is uncovered.

Welfare losses decrease when tax evasion detection rates and penalties are higher.

Implications for Australian tax policy

This research suggests that simply introducing a wealth tax may not achieve the desired outcomes and could even have unintended negative consequences.

Policymakers must consider the potential for tax evasion and the broader economic impacts before proceeding.

In the Australian context, recent evidence shows we respond to avoid and minimise tax increases.

For instance, with excise taxes on tobacco having increased by 282 per cent since 2013 (after stripping out inflation), more tobacco has traded in the black market.

More broadly, analysis of how Australians responded to changes in personal income tax rates between 2000 and 2018 showed taxpayers restructured taxable income in order to minimise their taxes.

The findings of Rotberg and Steinberg (2024) raise questions about the potential effectiveness and unintended consequences of a wealth tax in Australia.

The findings are a good reminder for policymakers to not only consider the direct, first-round effects but also the indirect, second, and subsequent effects.

Policymakers need to:

• Weigh up the unintended consequences of a wealth tax, particularly tax evasion and minimisation, as wealthier citizens have a greater ability to adjust taxable income.

• Quantify all economic effects, not just first-round impacts. An economy-wide model helps gauge the net economic impact in totality.

• Consider enforcement and penalties and factor in the costs of these measures in the overall expected change in welfare.

• Accurately assess tax avoidance behaviour in Australia. If it resembles the most optimistic Netherlands estimates, a wealth tax might work. However, if Australia is more like the US, such a tax may not be the best answer to the thorny problem of inequality, as it will leave everyone worse off.

David Williams-Chen is an economist and the founder of Positive Economics Advisory, specialising in economic modelling, policy analysis, and impact assessments

Originally published as why inheritance tax would seriously backfire in Australia