Why Brickworks will rise and fall on property

This high-profile building supplies giant is evolving right in front of us but there’s one thing that could stand in its way.

Investors need to start thinking of the Australian company behind Austral Bricks and Nubrick as a giant property trust with a brick manufacturing business on the side.

And that’s why the prospect of more super-sized interest rate rises threaten to rain down on the profit machine built up by long-term Brickworks chief executive Lindsay Partridge.

All things being equal, as interest rates rise through the economy property values fall. And this is likely to weigh on Brickworks’ vast land holdings which explains some of the deep discount in the company’s shares to its asset backing.

Right now though the nation’s biggest brick maker is swimming. Brickworks more than doubled its annual profit which came in at a record $746.1m for the past 12 months.

It delivered its ninth consecutive increase in full-year dividends to 63c, which means the company ranks as one of the few to either increase or maintain a dividend over nearly 50 years.

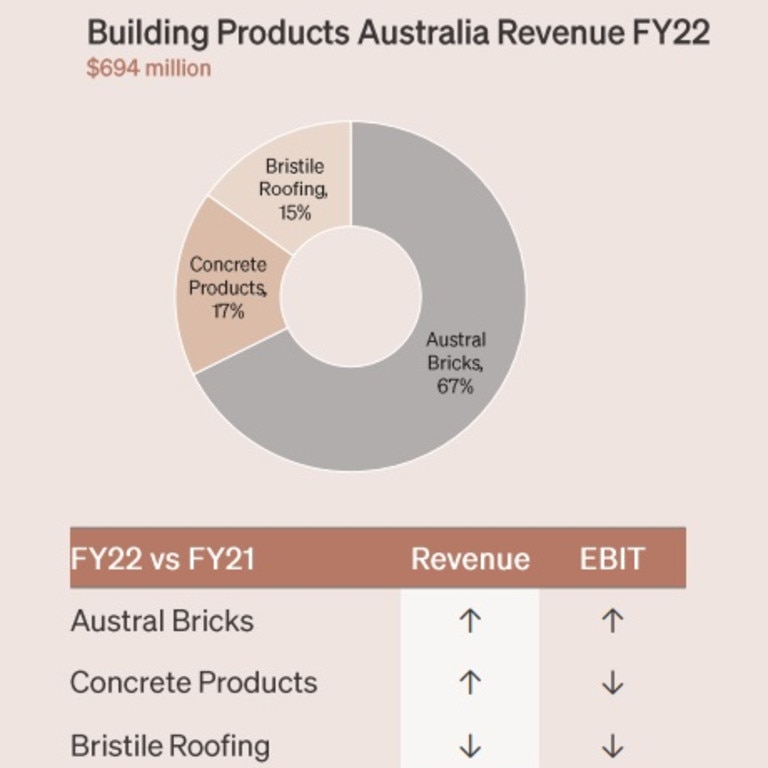

The headline result represents nearly a quarter of Brickworks’ entire market capitalisation and was substantially ahead of analyst expectations of around $580m. The top-line result was powered by a 155 per cent jump in the company’s property business.

Property now represents 73 per cent of Brickworks annual earnings with the traditional brick making business coming in below 7 per cent.

Brickworks is benefiting from the large slabs of land it acquired cheaply on the fringe of Sydney and parts of Melbourne over the decades which have become valuable as infrastructure has built up around them.

It now has more than 5000 hectares across Australia and North America, with the land originally earmarked as quarry sites to mine clay used to make bricks. The infrastructure boom means Brickworks has more than enough clay coming its way from building sites and tunnels across the capital cities.

Some of these property holdings have been tipped into an industrial property trust jointly owned with property major Goodman allowing Brickworks to capitalise on the warehouse boom.

One development – Oakdale – near the M7 road in western Sydney includes tenants such as tech giant Amazon and supermarket majors Woolworths and Coles, which is set to deliver a long lucrative rental stream for Brickworks.

Still, Brickworks is anchored in manufacturing and it has real world costs to contend with. Inflation and wage pressures remain an issue, although Partridge was able to lock in a long-term gas supply agreement before the Covid pandemic. This means it has been insulated from the worst of the recent surge in energy costs.

Brickworks is benefiting from its 42.7 per cent shareholding in investment house Washington H. Soul Pattinson, which now sits on the books at $2.42bn. It got a dividend windfall of $181m from WHSP’s booming coal exposure.

WHSP in turn has a cornerstone stake in Brickworks, a cross-shareholding that for decades has ensured the two companies remain takeover proof. But this arrangement has also weighed on Brickworks shares.

All the tangible assets, property and development sites sitting on Brickworks’ books have an inferred value of $5bn. As of Wednesday night Brickworks’ market capitalisation was sitting at a little over $3.3bn.

So this means the market has either got it wrong or Brickworks has a lot of blue sky built into its property book going into a rising interest rate market.

For now, Partridge is keeping a cautious footing. He has been paying down debt and that’s why some investors think the 2c a share full-year dividend rise is skinny compared to the property windfall in the past year.

“There’s a lot of moving parts that nobody knows the answer to,” he says. “And we’ve just got to be conservative until we find out how the year pans out”.

RBA’s indigestion

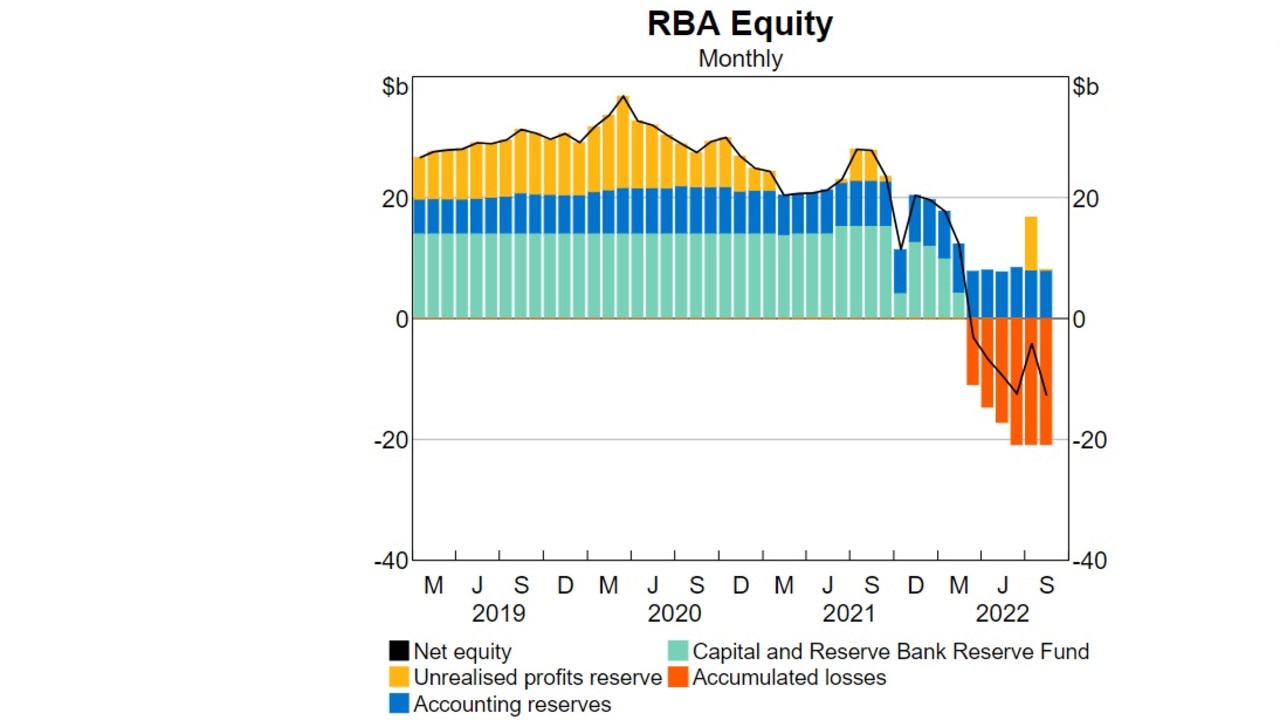

The nation’s central bank is suffering serious financial indigestion after throwing everything at rescuing the economy at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. In fact it’s going to take years for the Reserve Bank to rebuild its balance sheet.

In technical terms the RBA has “negative net equity”. That is everything it owes the world far outweighs all of its assets – including the pile of gold bars sitting below its headquarters in Sydney’s Martin Place.

If this was a business it would be out of business, but the RBA is no ordinary operation.

The total sum of this negative net equity is $12.4bn and comes after the central bank posted a whopping accounting loss of $36.7bn for the past financial year.

How it got there is important because it entered new territory as Covid-19 hit, as it set about buying more than $280bn worth of state and federal government bonds. The massive program – quantitative easing – was part of efforts to keep interest rates low and push money into the economy.

And now it is left holding a portfolio of these deeply underwater government bonds. This is the technical nature of the RBA’s negative net equity – if you bought a house and it is now worth 30 per cent less, life goes on as long as you can keep paying the bills.

However, a loss is released if the house is sold. This strongly suggests the RBA is unlikely to sell the underwater bonds and risk triggering a further loss.

On the RBA’s own numbers there would still be a $20bn “known” loss on the program between now and when the last bond bought during Covid matures in the coming decade. This is the difference for the premium it paid in the secondary market and the face value of the bonds.

Deputy governor Michele Bullock was refreshingly candid about the RBA being able to continue as normal and go about its business despite the deep hole on its balance sheet.

“We can create money,” she told a Bloomberg lunch in Sydney. “That’s what we did when we bought the bonds. We created money.

“The negative equity position will not affect the ability of the Reserve Bank to do its job,” Bullock said. However she concedes it’s not an ideal position, particularly in the face of possible future shocks, and the focus will be spent on getting the bank back to positive equity.

The timing of this could take years and really depends on further interest rates rises. In the topsy-turvy world of bonds, as interest rates rise the face value of the bond falls. The reverse is true as interest rates fall.

Right now we are in a rapidly-rising interest rate market and the RBA’s negative net equity position is likely to get worse before it gets better. The good news is that all those bonds being held by the RBA are paying an income that gives it some underlying earnings ($8.2bn in the past year) to offset the deep paper losses.

Unlike a normal business, there are no “going concern” issues with a central bank. Under the Reserve Bank Act, Canberra provides a guarantee to stand behind all the liabilities of the bank if they were called on at once.

In addition, since it has the ability to “create money”, the RBA can continue to pay its bills as they become due.

The technical aspect of it – which is the writedown on the value of its massive bond portfolio – also means that Treasurer Jim Chalmers won’t need to find funds in the upcoming Budget to prop up the bank.

However the other side to this is the many billions of dollars in dividends from the RBA the federal government has relied to help its budget over the past decade will no longer there.

Australia is not alone with a number of central banks around the world having similar issues of substantial accounting losses and, potentially, negative equity.

Some like the UK and New Zealand are protected given their respective governments provide an immediate indemnity for bond purchases by their central banks.

Policy debate

The push by the RBA to use the unconventional policy in buying bonds has fuelled intense debate across money markets over whether the central bank overstepped its mandate by artificially keeping interest rates low during the pandemic. The program is also being blamed for contributing to the massive inflationary breakout, which in turn has been driving up cash rates at rapid levels.

It also comes amid a looming review of the RBA launched by the Albanese government as it examines the role of the central bank in today’s economy.

While the bond buying is likely to be a net cost to the taxpayer given the RBA’s own estimate of losses and the prospect of years of lost dividends, the RBA’s own assessment said the program – which was designed to insulate the economy – clearly worked.

“The evidence suggests that the (bond purchase program) supported economic growth and jobs,” Bullock said.

While it is difficult to quantify “it is clear that the (bond purchase program), along with other policy measures, contributed to a strong recovery in economic activity and a sharp drop in unemployment,” she said.

A key benefit of the package of policy measures “was to provide insurance against the serious downside risks the economy was facing during the pandemic”.

Still, when pushed, Bullock conceded the bond program had only helped “at the margin” with the ultra-low cash rate doing all the heavy lifting in pushing the economy. Given the substantial cost of the program this suggests it could be a very long time before we see this massive bond buying spree used again.

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as Why Brickworks will rise and fall on property