Flirt or fleece? Romance scams robbed Australians of $201m in 2023

When love comes looking for you online, there might be something bigger at play.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One night in January last year, a Sydney media worker spent the “longest night of his life” negotiating a potentially career-ending move with a Philippines couple.

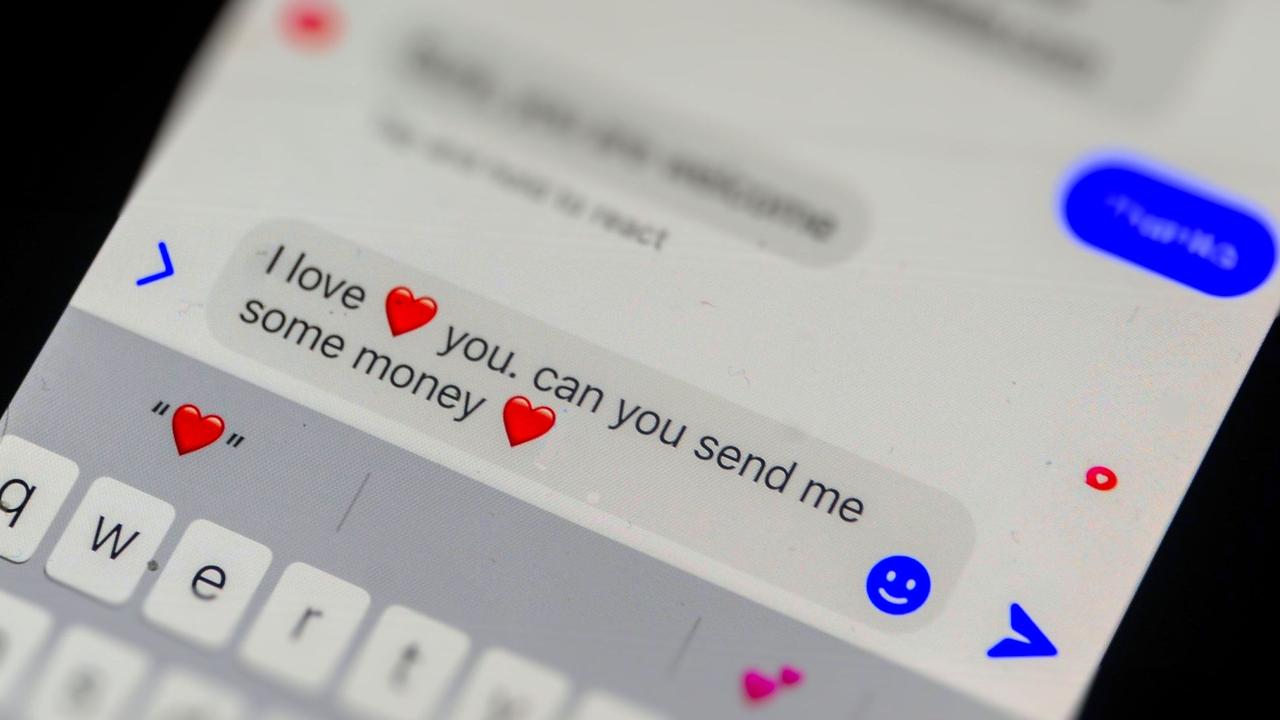

Belle, who he’d met on dating app Feeld two days earlier, had demanded he transfer $US5000 ($7900) to her boyfriend’s account via international money service Wise.

If he didn’t pay, she’d send explicit screenshots taken during a video call they’d had moments earlier to his entire list of followers on Instagram.

Sextortion is booming in Australia, with reports to identity and cyber support service IDCARE, which helped Australians recover $585m in 2024, rising 64 per cent in the past six months alone.

This relatively new genre, which forms part of the larger umbrella of romance scams, cost Australians $201m in 2023, equating to a rate of about $23,000 an hour. That’s near ten times the $25m lost to romance scams in 2013 and a tenth of the $2.74bn the entire scam industry took from Australians in 2023.

Criminals are increasingly targeting younger generations, including Jordan (not his real name), who are conditioned to a world in which dating apps and social media have made online connections and meeting strangers almost instantaneous.

“OK we’ve got u bro, give us money or everyone sees u jerking off,” read a message delivered to Jordan not long after the call.

Jordan had met Belle a couple of days earlier and, while the relationship progressed quickly, if his experience on Feeld was anything to go by, that wasn’t unusual. Feeld is a New York-headquartered company that bills itself as “the dating app for the curious”. It was “basically a more sex positive and kink-friendly dating app”, he says.

Jordan began using the app a month earlier. He’d already met two women and had relations within a few days of connecting. “Everyone’s more forward and open,” he said, adding Belle was even more forward than the rest.

“In a refreshing change of pace, she did the majority of the initiating. Which, in retrospect, should have been a red flag.”

Before long, Belle had asked to move off Feeld to Instagram. Her account was later banned on the dating app.

“Had we stayed on Feeld, I probably could have avoided the whole damn thing – her account was locked in some sort of conduct violation, I’m guessing this was a numbers game,” he said.

Belle’s Instagram account was “unspectacular”, but her back story as an international student in Sydney’s Bankstown who had come to study engineering seemed sound. One night during an exchange of explicit pictures, Belle had asked to use another app called Line.

The app, a product of Japan’s LY Corporation, is hugely popular in Southeast Asia including Thailand, and Japan, where it has about 84 million monthly users, according to Statista.

During an explicit video call, Belle had repeatedly asked him to show his face, as she had shown hers. The moment he did, he learned it wasn’t just the two of them on the line.

A man in the background, who Jordan understands to be her boyfriend, began to giggle and that’s when the threats began.

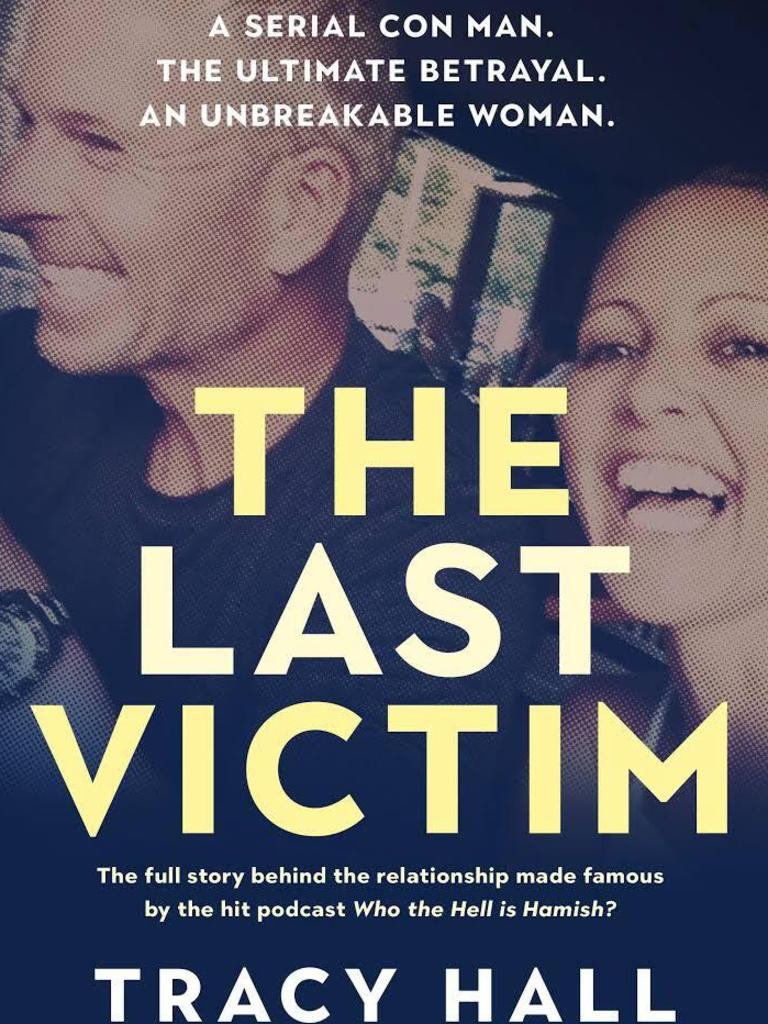

Romance scams, once thought to only target the middle-aged, are increasingly going after younger generations, and there’s no shortage of victims, particularly around annual celebrations such as Valentine’s Day, says Tracy Hall, author of The Last Victim.

Ms Hall was a victim of Hamish Watson, who was sentenced to jail in 2019 after swindling $7m from a number of victims.

This year she has produced a guide on romance scams with Tinder, one of the oldest and most popular dating apps.

Romance scams have grown so large that Tinder and other big tech players including Meta can no longer ignore them, recognising that their platforms are often the primary medium in which they take place.

“What we also are hearing is that one of the top scams that is hitting young people right now is sextortion,” Ms Hall said.

Such was the case for Jordan who, after several hours of antagonising negotiation, paid $US500 on the Wise service to Belle and her partner – a tenth of their original demand.

The couple continued to harass Jordan asking for more money, but he ignored them and two days later they gave up.

There was a misconception that romance scams only targeted older people who had accumulated wealth, Ms Hall said.

When it came to younger people, scammers were finding that their digital nature meant relationships moved faster.

“[Young people] start relationships online and they have these intense periods of connection that move very quickly, to the point where they feel comfortable enough to send explicit content to somebody who is a complete stranger,” she said.

“This is one of the fastest-growing scams globally, and it’s impacting young people significantly to the point where there are people dying by suicide.”

Ms Hall, who has now dedicated her time to scam prevention and awareness, said the industry was so big there was “now a scam for everyone”.

“We never think it’s going to happen to us, we all think we’re a bit smarter than we are,” she said.

Meta was also proactively tackling romance scams, confirming it had recently removed 116,000 pages and accounts across Instagram and Facebook related to romance scams from Nigeria, Gahan, D’Ivoire, Benin, Kenya and Cameroon.

It had also disrupted Kenya-linked scammers who had set up fake dating agencies offering to meet wealthy Westerners as well as targeting businessmen in Australia, the UK, the US and Europe with offers to meet African women.

More Coverage

Originally published as Flirt or fleece? Romance scams robbed Australians of $201m in 2023