‘Banking crisis that puts the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in its shade’ looms for China

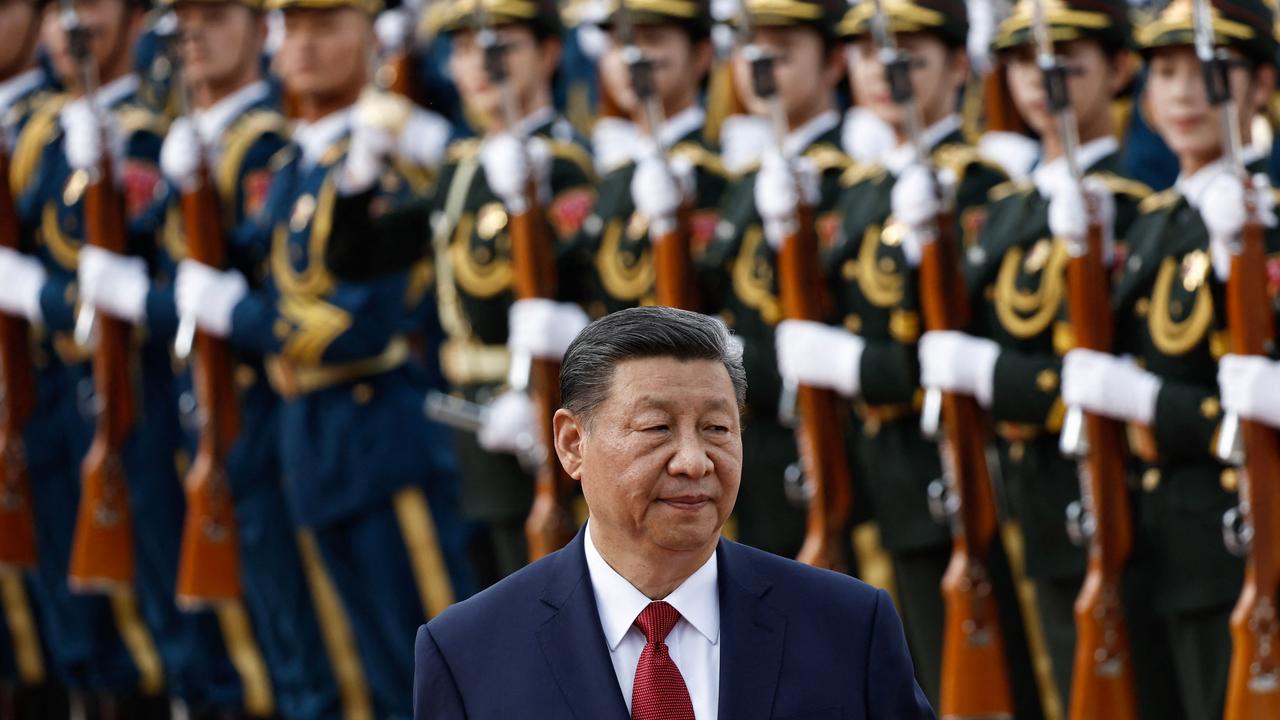

China’s eerie “ghost cities” provide cold, hard proof that Xi Jinping has failed as an “economic tsunami” threatens to unleash chaos.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

China’s government has applied an economic defibrillator to restart the nation’s beating heart. But the looming spectre of its expansive “ghost cities” may mean it’s already too late.

China’s “miracle” economic development of the nineties and noughties overheated.

Strict limitations on how its population can invest turned their new-found wealth into a blowtorch directed at residential real estate.

Eventually, actual accommodation demand was sated.

But the promise of future growth from the long-term exodus from country regions drove speculators onward.

The result: Vast urban “ghost cities” of uninhabited apartment blocks scattered across much of mainland China – and financially trapped family investors. Almost 100 million apartment units are standing empty. But their mortgages, rates and upkeep must still be paid for.

This week, China’s authoritarian Chairman Xi Jinping “responded to the concerns of the masses” and ordered something to be done about it.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) “must work to halt the real estate market decline and spur a stable recovery”, a readout from an irregular assembly of his Politburo power circle reads.

Shares in flagging property developers began to rally during the week after the central bank unleashed a tsunami of stimulus, and China’s provincial governments began to respond by abandoning home ownership controls.

“Significant steps are being taken to encourage homebuying during the coming holiday,” Shanghai-based real estate broker Yan Zhancai told the state-controlled South China Morning Post.

“Pent-up demand will be released, and we expect to receive a lot of inquiries from buyers.”

But behind the party line is an undeniable problem.

What buyers?

“Fundamentally, there are not enough people to fill the homes,” Peterson Institute for International Economics researcher Tianlei Huang told the Wall Street Journal.

Explosive growth

The Chinese Communist Party’s experiment with unrestrained capitalism has catapulted the country into the position of the world’s second-largest economy.

Beijing began aggressively encouraging an investment-driven economy in the 1990s. Its goal was to lift the nation’s standard of living. It wanted modern manufacturing, advanced education – and a military capable of confronting the United States.

This required a vast new urbanised population. And it got that.

Initially, Beijing focused on infrastructure. It built roads, bridges, railways and airports. It upgraded sewerage systems, electricity networks and generation. It developed new solar, wind and manufacturing technologies.

At the same time, the CCP encouraged its freshly unleashed entrepreneurs to launch into hi-tech industries – and real estate.

It was a boom waiting to happen.

People were living in overcrowded homes. At the same time, a torrent of ambitious country youth streamed into the cities in search of careers, wealth and a better life.

Construction surged.

The good times came.

But the Party, banks, developers – and investors – chose to ignore what they all knew was coming.

Chairman Deng Xiaoping imposed a one child policy in 1980. China’s population had almost doubled since 1949. And homelessness, unemployment and hunger threatened to overwhelm the Party state.

But the reproduction brakes were kept on too long.

Chairman Xi had them lifted in 2016. But it took until 2021 for him to realise his anticipated baby boom had not arrived. Now, he’s seeking ways to enforce a three child policy.

But Beijing has an unexpectedly urgent set of related problems: How to revive a stalled economy. What to do with so much unneeded property. And how to mollify so many trapped mum-and-dad investors.

Excited investors

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 was a real estate-based cash crisis emerging from the United States. Its poorly regulated property investors had been living on borrowed time – and borrowed money – far too long.

It wasn’t a lesson Beijing learned.

Instead, to tackle the crisis, it injected massive stimulus into real estate.

It thought government policy alone could lead to sustained economic growth, urban development and technical advancement.

Construction surged.

The good times didn’t end.

Soon, profitable investments began to dry up. Investors had nowhere to put their money.

But the CCP had another stimulus plan: Order the construction of entire new cities.

Australia’s iron ore mining industry cashed in. This, after all, needed vast quantities of structural steel.

Chinese family investors saved Canberra’s budget.

For the new middle class, real estate was one of the few safe and rewarding avenues of investment they were allowed. They couldn’t put their money into anything involving overseas companies or projects.

Soon, the sector was awash with cash.

China’s home ownership rate leaves the “Australian Dream” in its wake. Almost 90 per cent of households own their home. For Australia, that figure is 66 per cent – and falling. It was 70 per cent in 2006.

But, having nowhere else to put their money, Chinese family investors were forced into speculation.

Many bought second and third homes as holiday accommodation, rental streams and long-term investments.

Then they had to buy empty apartments – or fund yet more new ones – in the hope of future tenants or sales.

But China’s population is ageing. Urban migration is slowing. Demand for housing has dried up.

Little wonder property prices are collapsing.

And that family investors are saddled with debt.

Egregious implications

Real estate has been the powerhouse of the Chinese economy. It still directly contributes about 15 per cent to GDP (down from about 25 per cent a decade ago). Indirectly, through associated sales, maintenance and whitegoods industries, it still accounts for 30 per cent.

That’s why the downturn is rippling through the entire economy.

Property developers have raced ahead of demand. They acquired enormous debt in the rush to compete with each other over major new residential projects.

Many of those projects are now ghost cities.

Evergrande was just the first to collapse in 2023. Other top players have followed suit.

Now, Chairman Xi faces widespread fallout.

A banking crisis that puts the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in its shade is looming.

Developers are defaulting on their loans. But so too are family investors.

Forced sales are already flooding the market.

International analysts calculate there are about 90 million unoccupied and incomplete apartments.

And this has the potential to unleash an economic tsunami.

Some estimates warn that a 20 per cent drop in Chinese real estate activity could produce a five to 10 per cent fall in GDP.

Official data out of Beijing concedes the value of new homes fell 23.6 per cent for the year to August. That’s a slight improvement on the 24.3 per cent for the July-July period.

But the implications are still dire.

State media says Chairman Xi called an unusual assembly of his Politburo and ordered them to do something about it.

The Politburo, in turn, has instructed provincial governments to do something about it.

The official CCP readout of the top-level meeting is light on plans.

But it outlined overall policy goals, including reduced new housing supply, increased loans for projects demonstrating a measure of success and cutting mortgage rates.

This week, the People’s Bank of China cut interest rates by 0.5 per cent. It also lowered the deposit required for a second home purchase to 15 per cent, down from 25 per cent.

End of the road

“I don’t think the housing oversupply problem has a solution, really,” Huang told the Wall Street Journal.

“Fundamentally, it’s the problem of declining demographics. Ghost cities will remain ghostly.”

Earlier attempts at stimulus have so far failed to achieve results.

In May, Beijing offered $US42 billion in low-interest loans for state-owned businesses to buy empty commercial properties and convert them into affordable housing.

By June, only 4 per cent of that cash had been taken up.

Affordable housing isn’t a problem.

The Wall Street Journal cites economists as estimating that, of the 90 million vacant housing units, about 31 million are only partially completed. Some 50 million have been bought, but are unoccupied. Another 20 million have been paid for – but not built.

One of the resulting ghost cities was intended to be a new financial district on the scale of Manhattan: Yujiapu in Tianjin Province. However, entrepreneurs and government officials turned out to be in short supply. Now, its towering skyline is mainly made up of hollow shells.

Some ghosts, however, are showing signs of life.

Chenggong in Yunnan Province was almost empty when completed in 2013. Now, investors are working, with some success, to save it by turning it into a higher education hub with affordable accommodation.

The rest still largely rely on finding family buyers.

About 74 per cent of China’s city homeowners have already bought an investment property. Some 20 per cent own three or more.

Many of these homes are in rural and regional areas.

And that’s where populations are already in decline.

Current demographic projections expect China’s population to halve by the end of the century.

And Chairman Xi’s instruction for all families to have three children appears to be falling on deaf ears.

Meanwhile, his ageing population is looking for smaller houses closer to support services.

And house prices continue to fall.

The recent relaxation of mortgage rules and instructions to local governments to buy surplus stock has simply resulted in a slight shift of where housing debt resides.

And potential investors are keeping their wallets firmly in their pockets with little prospect for the property price bubble to be reinflated.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as ‘Banking crisis that puts the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in its shade’ looms for China