Is coal really dead? Why Australia is clinging to a dying industry

AS THE world turns away from coal, Australia seems to be holding on more tightly than ever and one surprising figure may reveal why.

Mining

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mining. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS THE world turns away from coal, Australia seems to be holding on more tightly than ever and one figure may reveal why.

Australia is already the fourth-largest coal producer in the world and contains the fourth-largest coal resources, after the United States, Russia and China.

With so much wealth in the ground, it’s something that’s not easy to give up.

Just ask the dozens of companies which have coal mining projects in the works.

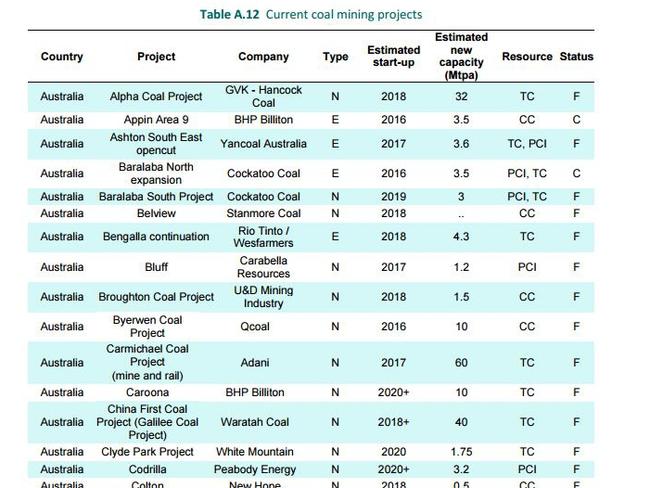

While Indian giant Adani’s Carmichael mine has been in the spotlight in recent years, the International Energy Agency’s Medium-Term Coal Market Report 2016 released in December highlighted just how many projects are in the pipeline.

In fact, the IEA found a staggering 63 proposed coal mining projects in Australia, according to publicly available information.

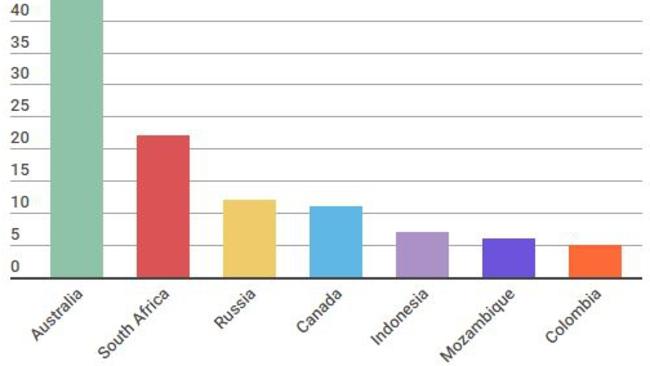

This compares with 22 projects in South Africa, 12 in Russia, 11 in Canada, seven in Indonesia, six in Mozambique and five in Colombia.

Some are committed but others are still in feasibility stage. The projects in Australia have been put forward by dozens of companies like BHP Billiton, Yancoal, Cockatoo Coal, Stanmore Coal, Qcoal, Waratah Coal, White Mountain, Peabody Energy, New Hope, Acacia Coal and many others.

But there’s very few new coal mining projects coming online around the world, with the majority postponed.

Low and decreasing prices for coal have discouraged investment and the IEA doesn’t expect this to change.

Prices have been dropping for more than four years. While there was a rebound in 2016, this was mainly attributed to policy changes in China to cut coal output, which pushed prices up.

The IEA expects prices to fall again, although they may recover a bit closer to 2021.

“Hence we do not see the momentum building for new mining investment,” the report says.

SO IS COAL DEAD?

While the International Energy Agency found global coal demand had stalled it was “too early to say that coal is dead”.

In the medium-term, from 2015 to 2021, demand for coal globally is expected to keep growing — at a low rate of 0.6 per cent per year — and the main driver of growth will be India.

One way to understand this potential is to consider this fact:

India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh combined account for more than one quarter of the world’s population but only 7 per cent of its electricity use.

In fact many of the citizens don’t have electricity, even though they live in countries with large coal reserves.

However in India, these reserves are mostly low-quality coal and this is where Australia has an opportunity.

Australian coal is typically of high quality, its thermal coal has a high-energy and low-ash content that makes it suitable for modern high-efficiency low-emissions coal-based power generation technologies.

Although it seems counter-intuitive, an IEA spokesman, said world demand for coal would still likely support the construction of a new mine.

Long-term demand trends in the IEA’s World Energy Outlook continue to forecast increased coal demand through to 2040 under its central scenario.

“Whereas the increase is very slow, there is a need for new mines in order to replace the production loss in some of the existing mines,” the report says.

“Therefore, our central scenario is assuming production of new coal mines.”

While low carbon technologies have been found for power generation (including wind and solar), finding viable options for decarbonisation of industrial processes, like producing steel and making cement, has been more challenging.

“Therefore, coal and CCS (carbon capture and storage) will likely need to be used,” an IEA analyst told news.com.au.

But the report also noted the difficulty in getting finance for coal mining investments, which are penalised by the policies of many international financial institutions, investment funds, banks, university funds and others which are turning away from financing coal, particularly in the US and Europe.

In Australia railway capacity has also traditionally been a limiting factor for coal exports.

In fact the future of Adani’s mega Carmichael coal mine in the Galilee Basin may ultimately depend on whether it can get financing and whether Australia agrees to give it a $1 billion taxpayer funded loan to build a rail line.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ‘CLEAN COAL’

While there’s still going to be demand for coal, meeting targets set in the Paris Agreement is going to be an issue.

“Without CCS (carbon capture and storage) or technological innovation to use captured carbon for commercial purposes, coal must be virtually eliminated if Paris targets are to be met,” the IEA report said.

“(This) can be challenging in power generation and even more so in industrial applications.”

Coal use is responsible for 45 per cent of energy-related carbon emissions, which need to be cut back if global warming is to be kept under two degrees.

“Yet one year on from Paris, there is little indication governments are acting to enforce limits on carbon emissions that would allow investment in CCS to happen,” the report said.

However, critics are sceptical that coal can actually be clean and private companies have been unwilling to put money into the risky venture. The IEA said this meant government funding was essential to getting CCS projects off the ground

“Especially in light of the lengthy time frames that are often involved in developing first-of-a-kind, large-scale integrated projects,” the report said.

The IEA noted that without new policy or financial measures, momentum for CCS projects would likely stall by 2020.

“There has been limited CCS project activity in recent years, with no final investment decisions for large-scale projects announced since 2014,” it said.

In fact two projects were abandoned in the UK after government funding was withdrawn.

As of November 2016, there were 15 large-scale CCS projects including for coal-fired power generation. Six more projects are expected to start operating before the end of 2017, including the world’s first large-scale bioenergy with CCS project.

AUSTRALIA BUCKING THE TREND

While globally, coal supply decreased for the second year in a row in 2015, India and Australia managed to buck this trend.

In Australia, producers continued to cut costs, helping to increase production by 4.1 per cent despite harsh market conditions.

Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter and Hunter Valley Coal Chain in NSW is the largest export operation in the world.

More than 80 per cent of the country’s coal is exported. In 2015 most of this went to Japan (33 per cent), China (18 per cent), Korea (15 per cent) and India (12 per cent).

Australia earned $US28 billion from its coal exports in 2015 but this was about 20 per cent lower than in 2014 because of lower prices.

Several mines also closed in 2015 due to low prices.

But Australia’s healthy result was helped by a 7 per cent increase in exports to India, which also managed to increase its own coal production by 5.1 per cent because of growing domestic demand.

India is now the second highest consumer of coal after China, consuming 11.8 per cent of the world’s resource in 2015.

Despite the recent growth, the IEA predicts the use of coal for energy will drop from 41 per cent in 2013 to about 36 per cent in 2021.

“Our forecast shows a slight increase after a few years of decrease, reaching 2014 levels only in 2021,” the report says, adding “such a growth path would depend greatly on the Chinese”.

But coal markets are harder to predict than ever, with the IEA saying actual demand had been below forecasts since 2013.

It’s unclear how long Australia can continue to ride a wave of prosperity on the back of coal, and while it has enough accessible high-quality hard coal to last another 125 years, much of it may ultimately need to remain in the ground.

Email: charis.chang@news.com.au | Twitter: @charischang2

Originally published as Is coal really dead? Why Australia is clinging to a dying industry