Yoon’s South Korean presidency on borrowed time after martial law madness in Seoul

Yoon Suk Yeol’s South Korean presidency is in peril after his brazen attempt to break through a domestic political logjam by imposing martial law was followed by a humiliating backflip and rising calls for his impeachment.

Yoon Suk Yeol’s South Korean presidency is in peril after his brazen attempt to break through a domestic political logjam by imposing martial law was followed by a humiliating backflip and rising calls for his impeachment.

South Korea’s main opposition party accused Mr Yoon of insurrection after he ordered almost 300 martial law troops into the National Assembly late on Tuesday night, many dropped by helicopter.

“He must step down,” said Democratic Party floor leader Park Chan-dae on Wednesday.

Many analysts in Seoul and overseas were predicting an end to Mr Yoon’s presidency, which is only halfway through its five-year term. The opposition called for impeachment proceedings, as it claimed Mr Yoon’s actions were a “grave violation of our constitution” that amounted “to a clear act of treason”.

Pressure ratcheted up on Mr Yoon in the hours after he announced in a television address at 4.30am (6.30am AEDT) that he was lifting martial law after it had been blocked in an extraordinary vote in the assembly.

In an earlier televised address, he had stunned the nation by declaring he was going to impose martial law, citing “anti-state forces” that were paralysing the operation of the nation with impeachment motions and a downsized budget bill.

Following the debacle, presidential chief of staff Chung Jin-suk and National Security Adviser Shin Won-sik offered to resign en masse, alongside eight other senior aides.

South Korea’s largest umbrella labour union called an “indefinite general strike” in the world’s 12th biggest economy until Mr Yoon resigned. The 1.2 million-member Korean Confederation of Trade Unions accused Mr Yoon of an “irrational and anti-democratic measure”, which had “declared the end of (his) own power”.

In the US, Seoul’s leading military ally, Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell said Washington was watching with “grave concern” and engaging with the South Korean government “at every level”.

A US National Security Council spokesman said later that Washington was “relieved President Yoon has reversed course on his concerning declaration of martial law and respected the … National Assembly’s vote to end it.”

The country’s Kospi stock index fell by almost 2 per cent in Wednesday’s morning session.

Mr Yoon’s surprising move hearkened back to an era of authoritarian leaders that the country had not seen since its move to democracy in the 1980s, and it was immediately denounced by the opposition and the leader of the president’s own party.

Parliament acted swiftly after martial law was imposed, with Speaker Woo Won Shik declaring that the law was “invalid” and that politicians would “protect democracy with the people”.

In all, martial law was in effect for about six hours.

Mr Yoon, a former prosecutor and political novice when he was elected with a narrow victory in 2022, had earned a reputation for being stubborn and for making unilateral decisions.

His approval rating dropped to 19 per cent in the latest Gallup poll last week, with many expressing dissatisfaction over his handling of the economy and controversies involving his wife, Kim Keon-hee.

In March, his government sent former defence minister Lee Jong-sup to be South Korea’s new ambassador to Australia, but the incoming envoy was forced to return to Seoul 10 days later amid a corruption investigation.

Mr Lee had not even presented his credentials to Australia’s governor-general.

The Australian government said on Wednesday that it was “concerned by the political situation” in South Korea.

“As a close partner and friend of the Republic of Korea, we hope for a democratic and peaceful resolution for the Korean people,” a spokeswoman for Foreign Minister Penny Wong said.

James Choi, Australia’s former ambassador to South Korea, said for all the chaos, the episode had demonstrated the effectiveness of the country’s political institutions.

He noted the wave of huge anti-government protests that swept South Korea during the presidency of Mr Yoon’s predecessor, Moon Jae-in, following a series of corruption scandals, and the impeachment of Mr Moon’s predecessor Park Geun-hye in 2017.

“Despite all the drama, Korean institutions and democratic principles won out. It’s proved to be the case again,” Mr Choi said.

He said Canberra and Seoul would continue to work more closely together because of the “geostrategic positioning of our two countries”, which was not dependent on any single leader.

Earlier this year, Seoul joined Tokyo in backing an Australian-led statement accusing China of cyberspying, part of an effort by Canberra to better co-ordinate with South Korea on shared concerns about Beijing.

Early in his presidency, Yoon had signalled an interest in South Korea joining the Quad.

For now, South Korea’s executive is likely to be subsumed by the ongoing political fallout.

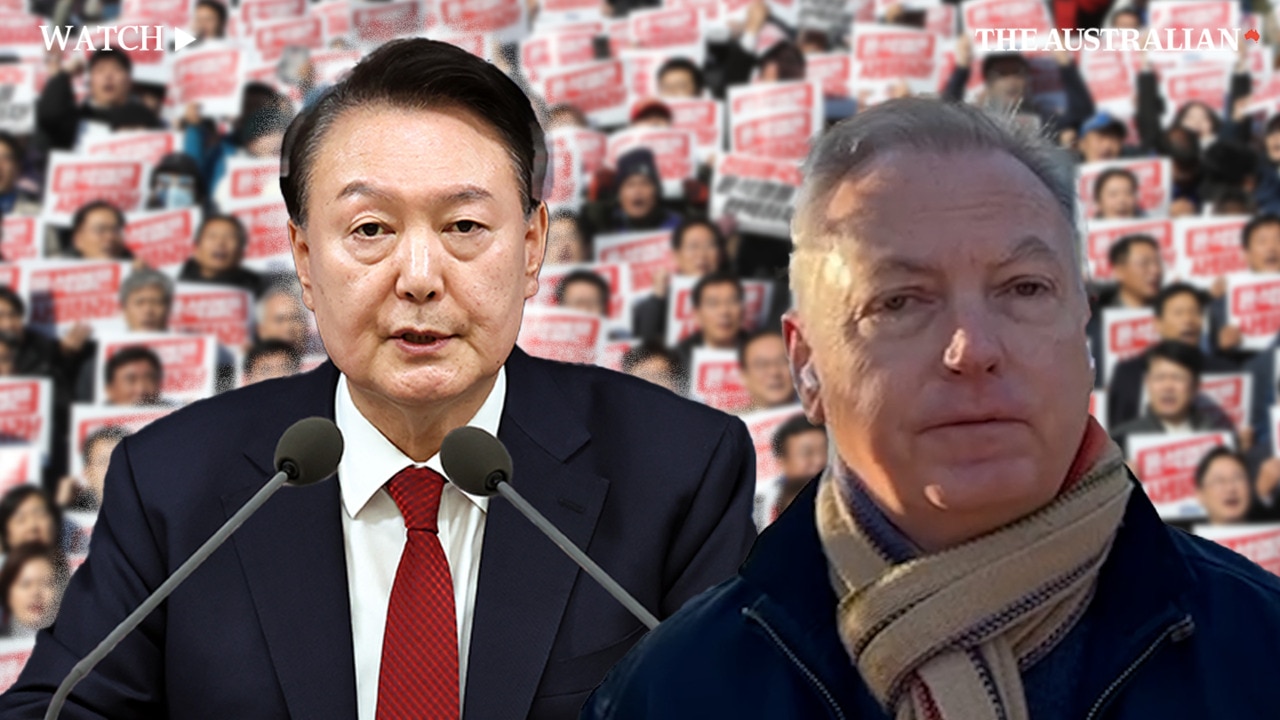

“There will be no political bandwidth available,” wrote Australian Strategic Policy Institute senior analyst Euan Graham in The Strategist on Wednesday, assessing Seoul’s foreign policy trajectory. “Given the scale of this debacle, it’s hard to see how Yoon can remain in office for long.”

Additional reporting: AFP

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout