‘We owe him a debt greater than he’ll ever know’: Prince Philip dies aged 99

For over 70 years the Duke of Edinburgh was Queen Elizabeth’s strongest support, through the monarchy’s best years and its worst

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh: 1921 – 2021

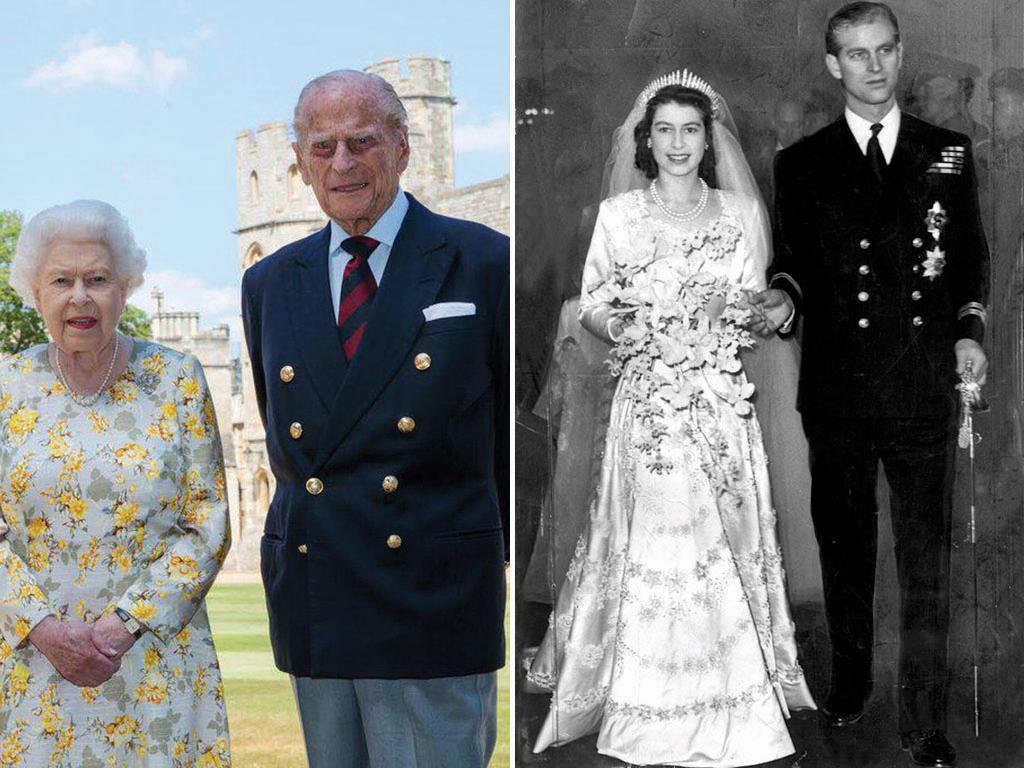

In the late autumn of 1947, during his honeymoon at Balmoral in Scotland, Philip Mountbatten sat down at his desk and wrote a letter to his new mother-in-law, the Queen. “Lilibet is the only ‘thing’ in this world which is absolutely real to me,” he wrote. “And my ambition is to weld the two of us into a new combined existence … Cherish Lilibet? I wonder if that word is enough to express what is in me.”

Fifty years later, on their golden wedding anniversary, Queen Elizabeth paid her own, very rare public tribute to her husband, her “strength and stay all these years,” speaking, for the first time, of his “constant love and help” throughout their years together.

“I, and his whole family and this and many other countries owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know,” she told her audience, and him.

For a woman who rarely shows emotion in public or even in private it was an extraordinary display of love for the man who had walked with her for the last five decades — albeit always two steps behind.

For 70 years the Duke of Edinburgh was Queen Elizabeth’s strongest support, through the monarchy’s best years and its worst.

Abrasive, gaffe-prone, bad-tempered; the descriptions, one dimensional as they are, have come to cloak Philip so thoroughly the public seldom see the man who lives behind them.

Philip has never been just the Queen’s consort, fated always to walk in her shadow. He joined the royal family as an outsider, despised and bullied by rigid, elitist courtiers, forced to give up his flourishing naval career for a secondary role at his wife’s side. But he put his own stamp on the monarchy, helped drag it into the 20th century, made it less stuffy, more relevant to the lives of ordinary people.

A true renaissance man with an interested and inquiring mind, he became a galvanising force in areas as diverse as science, design and conservation. By the time he retired in November 2017 he was patron and president of more than 780 organisations, championing causes from saving wild life to helping youth; most notably through his Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme, which he regarded as his greatest achievement, and which has helped millions of young people all over the world.

His personal interests ranged from polo, sailing and flying to art and cooking. For years he took an electric frying pan with him everywhere to cook breakfast for his wife and it was he, rather than the Queen who organised the menus for state banquets at Buckingham Palace. An avid art collector, he was immensely proud of discovering two hitherto unrecognised George Stubbs’ in the cellar of Windsor Castle and he was instrumental in opening to the public the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace.

He had a long, affectionate relationship with Australia — forgotten in the furore over the notorious decision by former prime minister Tony Abbott in 2015 to offer him a knighthood. He first visited in 1940 as a midshipman on the battleship Ramilles, using his four days shore leave to go and work as a jackaroo. He came again in 1945 and accompanied the Queen in 1954 when she became the first reigning monarch to visit Australia. He opened the Melbourne Olympics in 1956 and the Commonwealth Games in Perth in 1962. He was proud that over 700,000 young Australians completed the Duke of Edinburgh Awards but made it clear as far back as 1967 that Australia should become a republic if it felt it was getting nothing from the monarchy. “If the monarchy is of value retain it. If not, get rid of it,” he said at the time.

Regardless of what he thought was right for others, his first duty, his most important, was always to the Queen. Mike Parker, an Australian wartime naval pal who became his first private secretary, said Philip had told him early on that his constant job was “looking after the Queen in first place, second and third”.

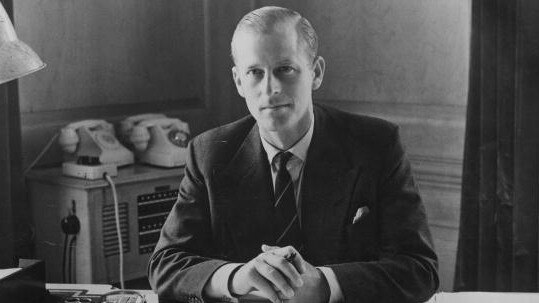

When he married then Princess Elizabeth in November 1947 the adulation that surrounded the young royal couple was easily as great as that, 33 years later, for Charles and Diana. Philip – handsome and charismatic with a valiant war record — was a hero for the age. But he was an immensely complex man with a painful past.

At just 26 he had already lost much that makes up the fabric of a life; he had suffered a lonely childhood riven with tragedy and had no real family, no home, not even a country to call his own. Marriage brought him all of these. But it also stripped him of his independence, a flourishing naval career and, for a time, his sense of self.

Philip was born Prince Philippos of Greece and Denmark on June 10 1921 on the Greek island of Corfu, on the dining room table of the family villa Mon Repos, the fifth child of Prince Andrew (Andrea) of Greece and Princess Alice of Battenberg. He was registered in Corfu Town as Philippos, sixth in line to the Greek throne, with the dynastic name of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glucksburg. Like most European royalty he had a mixed heritage; his Danish grandfather came to the Greek throne by a series of coincidences and his mother, a German aristocrat, was both Queen Victoria’s great-granddaughter and the Russian Tsar’s niece.

The young Philip never really knew a settled life: when he was just 18 months old, with Greece in political turmoil and Andrew blamed in part for the failure of the Greco-Turkish war the family was exiled, rattling around Europe until they eventually settled in a borrowed house in St Cloud, near Paris, where they struggled to pay even their household bills.

For the next 25 years, until he and Elizabeth moved into Clarence House in 1949, Philip had no real home.

Both parents doted on Philip, the first boy after four girls but he seldom saw them and, with the closest sister to him seven years his senior he had a solitary childhood. By the time he was five Philip’s parents were drifting apart, partly due to Alice’s fragile mental health and he and his sisters were regularly packed off to friends and relatives around Europe. In 1930, Alice was diagnosed with schizophrenia and committed to a sanatorium, and Andrew closed the Paris home and moved to the south of France, ending any semblance of family life. With his sisters all married to German aristocracy Philip was sent to England to live with Alice’s brother George Mountbatten, Marquess of Milford Haven. He seldom saw his father and for years didn’t see or hear from his mother at all.

“It’s simply what happened,” he told one biographer. “The family broke up. My mother was ill, my sisters were married, my father was in the south of France. I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.”

It was from this peripatetic, splintered childhood that Philip developed his enormous emotional reserve, the controlled, stern exterior that would become his signature. But even when he was very young a cousin noted that although he had “nothing”, he never felt sorry for himself. “You are where you are in life so get on with it,” was his philosophy even then, she said.

In England he was sent first to Cheam prep school then to Gordonstoun, where he thrived on its strict regime of physical fitness. At both schools, he excelled at sports; at Gordonstoun he learned to sail, beginning a lifelong love affair with the sea. Kurt Hahn, the headmaster of Gordonstoun, recalled his “undefeated spirit.”

‘I just to get on with it. You do. One does.’

But tragedy marked these years; in 1936, aged 15 he lost his sister Cecile and her husband George, Grand Duke of Hesse in an airplane accident. Hahn, who broke the news to him, recalled: “His sorrow was that of a man.” The loss affected him deeply. His childhood friend Gina Wernher recalled: “He showed me a little bit of wood from the aeroplane … it meant a lot to him.”

At the funeral at Darmstadt near Frankfurt, Philip’s complicated heritage was on display. As he walked behind the coffin alongside his remaining brothers-in-law, two of whom were fervent Nazis, the crowd gave them the Heil Hitler salute. Goering was among the mourners and Hitler and Goebbels sent messages of sympathy.

Two years later Philip’s uncle George died and his brother, Lord Louis ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten, took over the role of father figure. Mountbatten, an enormously influential figure in Philip’s life, thought of him as a son and had great ambitions for him; he steered Philip away from his dream of becoming a fighter pilot, and guided him to Dartmouth Naval College, where only Philip’s appalling spelling prevented him from passing out with top marks.

After Dartmouth, with England at war Philip expected to join the Royal Navy immediately but as a “neutral foreigner” he was barred from active service and had to wait until 1940 when Italy joined the war, dragging Greece into the conflict. He went on to serve with distinction on a series of battleships, rising to second in command, and mentioned in dispatches for his valour.

It was also Mountbatten who engineered Philip’s first significant encounter with the then 13 year-old Elizabeth on July 22, 1939, by inviting the royal family to tour the naval college. Philip, then just 17, didn’t seem to appreciate how momentous the meeting would turn out to be. The princesses’ governess Marion Crawford (“Crawfie”) remembered him as being “rather offhand” toward “Lilibet”. “He was quite polite to (Elizabeth) but did not pay her any special attention,” she said later.

But Elizabeth was entranced with the dashing young naval cadet. Throughout the war, their friendship grew, encouraged by Mountbatten, and on leave Philip was often invited to Windsor Castle. After one such visit he wrote a touching thank-you letter to the Queen in which he told her of his gratitude for the “simple enjoyment of family pleasures and amusements and the feeling that I am welcome to share them.”

King George and Queen Elizabeth didn’t at first approve of Philip’s courtship of their daughter; the Queen thought him rough and uneducated and referred to him as the “Hun” while the King worried that Elizabeth hadn’t met any men her own age. But they became fond of Philip, and by the time he proposed in 1946, they knew that, at least for Elizabeth Philip was, as she had told Crawfie years earlier, “the one.”

Before he could marry, however, Philip had to loosen the ties to his heritage. He had to give up his Greek nationality and become a commoner, abandoning both his right to the Greek throne and his family’s dynastic name because of its German connotations. He also became a British citizen, taking his maternal family’s name of Mountbatten.

Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, royal outsider

Philip was made Duke of Edinburgh on November 20, 1947, the morning of the royal wedding. But his status as outsider was underlined even on what should have been the happiest of occasions. He was bereft of family support in the lead-up to the day; his sisters were banned from the wedding because of their German husbands – the war was still too recent for a German presence – and, his father having died in 1944, his only immediate relative in Westminster Abbey was his mother Alice who sat with her mother Victoria and her own relations, the Mountbattens.

In these grey post-war years the royal wedding lit up England and the country fell in love with Philip. But behind palace doors, the courtiers were “absolutely bloody to him,” as his friend Lord Brabourne remembered.

Mike Parker recalled: “Philip was constantly being squashed, snubbed, ticked off, rapped over the knuckles. It was intolerable.”

Although he chafed at the rigidity of royal life there was freedom in these early years of marriage. The young couple moved into Clarence House and Philip took on the role of renovating it, turning it into a real home – the first he could call his own. They started a family immediately: Charles was born in 1948 and Anne followed in 1950. Philip was described by staff as a devoted father, if one with strict ideas of how he wanted his children to behave.

Infidelity rumours swirl

But it was also in these early years that the first rumours of infidelity began, which would haunt Philip throughout his life. According to biographer Ingrid Seward, they started after he was befriended by the society photographer Baron Nahum who inducted him into the “Thursday Club”, a louche social circle a world away from the Palace. A month before Charles was born, Nahum introduced Philip to Pat Kirkwood, a beautiful comedy star who was the first of a string of women whose names became linked to Philips’s. Others included novelist Daphne Du Maurier and the cabaret star Helen Cordet. None of the rumours have been proven, and on her death Kirkwood’s fourth husband produced a cache of letters which he said proved she and Philip had never been anything but good friends. But biographer Sarah Bradford remains adamant he was unfaithful, although not with Kirkwood. “He’s never been one for chasing actresses,” she has said. “The women he goes for are always younger than him, usually beautiful and highly aristocratic. The Queen accepts it. I think she thinks that’s how men are.”

Probably the happiest time in the couple’s life came when Philip was posted to Malta as commander of the ship Chequers. Leaving Charles and, then, Anne back in England, Elizabeth joined him there for extended periods, and they lived the carefree life of any young couple. Elizabeth in particular was able to live a life more ordinary, handling money and visiting the hairdresser for the first time.

Elizabeth crowned Queen

Everything changed in 1952 on the premature death of King George VI. Elizabeth and Philip, in Kenya as part of a royal tour that was supposed to take in Africa, Australia and NZ, were at Treetops hotel when the news was brought to Philip. Elizabeth’s lady-in-waiting Pamela Mountbatten recalled: “It was as though the world had fallen on him. He put a newspaper over his face and just remained like that for about five minutes. And then he pulled himself together and said he must go and find the princess ….”

The change in their lives was to be much harder for Philip than Elizabeth. Her whole life had been in preparation for this moment. His had not. He had expected that he had at least 15 years or more of freedom, to advance his naval career and to enjoy at least a semi-normal family life.

The first sign of his new role was when their plane landed back in England and Philip remained behind in the cabin as his wife went down the aircraft steps alone to meet officials. He would soon start to lose all those parts of him that were most important. First to go was his naval career; a loss he still felt decades later, telling one interviewer: “It was not my ambition to be president of the Mint Advisory Committee. I didn’t want to be president of WWF. I’d much rather have stayed in the Navy, frankly.”

Then he lost the right to pass his name on to his children, when the Queen decided they would take her name, Windsor. It was a bitter blow. He famously said: “I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his children. I’m nothing but a bloody amoeba.” It wasn’t until Andrew was born that the Privy Council decreed the couple’s children would henceforth be called Mountbatten-Windsor.

Aware that his sense of self was slipping, the Queen gave him the job of organising the coronation, where he knelt before her on June 2, 1953, swearing to be her “liegeman of life and limb.”

The gaffes begin

In that role, he became the perfect foil for his wife. Her shyness made her appear reserved, even chilly but when she was having difficult putting people at their ease, the Duke would stroll up and crack a joke to diffuse the tension. Sometimes the jokes misfired; the famous gaffes had already made their appearance even before the couple were married. In 1947, on the way back from a royal visit to Clydesdale, the royal train was delayed in a siding and Philip went, with the princess’s secretary Jock Coleville, to the signal box. Colville reported an “appalling gaffe” when the signalman joked he was waiting for someone to die in order to be promoted, to which Philip responded; “Like me!”

He was very aware of his tendency to make gaffes: he once told some guests he was “a specialist in dontopedalogy — the art of opening your mouth and putting your foot in it.”

But his breezy irreverence endeared him to the public, making its appearance even at formal dinners at Buckingham Palace where he was often seen examining a menu written in elaborate French before turning to his guests and joking: “Ah good. Fish and chips again”.

Even when he retired he couldn’t help a joke; when the mathematician Michael Atiyah said: “I’m sorry to hear you’re standing down,” Philip replied: “Well, I can’t stand up much longer.”

In private, Philip was never afraid to speak his mind if he thought the Queen was making a wrong decision; staff were shocked when they first overheard him shouting at his wife or telling her not to be “bloody silly,” during some argument. But he also made her see the lighter side of their structured life. If staff were shocked at his ripe language during arguments, they were equally surprised when they saw him chasing the giggling queen through the palace corridors, wearing a giant set of false teeth.

His forthrightness and his humour helped give the new Queen Elizabeth confidence: in 1957 Time magazine credited him with transforming his “mousy, slightly frumpy and occasionally frosty bride into a self-confidently stylish and often radiantly warm young matron.”

In turn, the Queen supported him in carving out his own role not only at her side but independently. He began to make his presence felt almost immediately, at first by modernising Buckingham Palace then by taking over the management of the royal estates, turning the farms at Sandringham and Windsor into profitable concerns and supplying the royal households with food.

He started to make his mark in the outside world, too. London’s The Times described him as being in step with the modern world, while other commentators credited him with helping the British see themselves as a modern and innovative people

A stern, sometimes brutal father

He was also very much the head of the household, particularly where the children were concerned. Like most aristocrats of their time, Elizabeth and Philip were hands-off parents, especially with Charles and Anne, who were brought up mainly by nannies. But while Elizabeth was always slightly distant with the children, Philip was more playful; a visitor to Buckingham Palace was once surprised to see him, stark naked in the palace pool, teaching his children to swim.

It was also he who broke with tradition by insisting their children were educated outside the palace walls to prepare for the exigencies of modern life. Charles followed his father to Cheam and Gordonstoun which he hated for the same reasons his father loved them, while Anne loved her days at Benenden.

But Philip, who had been forged by his traumatic childhood, was a stern, sometimes brutal father. He was impatient with weakness in others, and was disappointed in the sensitive Charles, often treating him harshly. Charles became closer to Mountbatten than his father, calling him “honorary grandfather,” and was devastated when Mountbatten was killed by the IRA in 1979. The distance between Charles and Philip was revealed at its most stark when they received Mountbatten’s body from Lydd airport on its way back from Ireland. Philip masked his sorrow behind a brusque façade and was more irritated than sympathetic at Charles’ visible grief.

He was closer to Anne, who shared his passions for horse riding and sailing but he enjoyed fatherhood more the second time around, with Andrew and Edward. Andrew remembers him reading the two young princes bedtime stories, or getting them to read to him. Of all his children, he was closest to Edward. In 1987, when Edward dropped out of the Marines the Queen was icily angry but Philip, who most expected to be outraged, was hugely supportive of what he thought a brave decision.

Because he gave up so much for his wife and the Crown, putting duty above all else, he expected his children and those who joined the royal family to do the same. He at first welcomed both Charles’ wife Diana Spencer and Andrew’s wife Sarah Ferguson into the royal family; he particularly enjoyed the company of Sarah, who shared his earthy sense of humour.

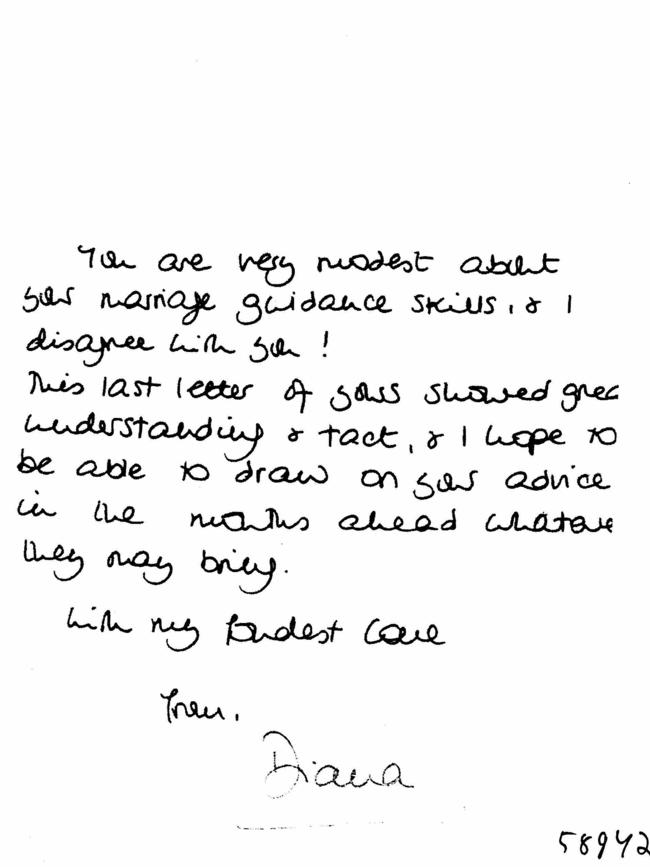

As Diana’s marriage to Charles became troubled she poured out her troubles to Philip, beginning her letters; “Dearest Pa,” and he wrote her surprisingly affectionate letters of advice, explaining that he knew first-hand the difficulties of marrying into The Firm as the family calls itself.

But when the young women put their own happiness before their duty, he was unforgiving. When Sarah and Andrew divorced in 1996 and Sarah had two scandalous and highly publicised love affairs he banned her from all the royal residences when he was there. Although Sarah and Andrew retained a close friendship, the ban remained throughout the rest of Philip’s life.

His relationship with Diana was more ambivalent; he tried hard to persuade her to remain in the marriage, but in the end it was he who insisted the couple divorce, as the only way out of the mess their marriage had become.

Annus horribilis: divorce and Diana’s death

When the Queen declared 1992 their “annus horribilis”, the principal cause was that the marriages of three of their four children were ending, but Diana’s death in 1997 was the lowest point of the monarchy: the anger of the British people was palpable at the way they felt the family treated her, and the royals’ refusal to return to London from Balmoral in the weeks after she died. But the Queen and Philip weathered it together, in part by concentrating on the welfare of Charles and Diana’s sons, William and Harry. The boys were devoted to both their grandparents, and at Diana’s funeral it was Philip, not Charles who the then 15-year-old William demanded walk beside him as they followed his mother’s coffin. It was also Philip who, as the cortege passed under Admiralty Arch, put a comforting arm around the shoulder of the grieving boy.

Seventeen years later, 2019 brought another annus horribilis, with the shine coming off the public’s early adoration of Harry and Meghan Markle and, far more damaging for The Firm, the scandal over Prince Andrew’s links with convicted pedophile Jeffrey Epstein.

As the scandal threatened to spiral out of control, Philip showed that, despite being retired, he still held the reins when it came to his family. After Andrew’s disastrous interview on the BBC, including his denials of the claim of one victim that she was trafficked to have sex with him, Philip summoned his son to Sandringham, his home since his retirement, to order Andrew to step down from his royal duties. In a tense meeting, Philip told Andrew he had no choice but to step down because his behaviour was putting the monarchy at risk.

Later life

Between these two nadirs, however, life for both Elizabeth and Philip was, in general, peaceful. Although the Queen grieved the loss of the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, who died within months of each other in 2002, they saw Charles settle into life with his second wife Camilla, both William and Harry happily married and the arrival of great-grandchildren, among them William’s son George, third in line to the throne and Archie, Harry’s son with Meghan.

In latter years, his increasing age meant Philip had to replace his beloved polo with carriage driving and as his life became more sedentary the Queen would tease him for his addiction to TV cooking shows. But the rhythm of their life remained little changed down the decades. Royal duties allowing, weekends were spent at Windsor, Christmas at Sandringham with pheasant and partridge shoots, and summer at Balmoral, with more field sports in the form of grouse shooting and deer stalking.

The coronavirus pandemic saw the pair locked down in Windsor Castle, spending more time under the same roof for a prolonged period than they had for many years.

The Duke of Edinburgh had been spending much of his retirement at his cottage in the sanctuary of the Sandringham estate, more than 150km away from the Queen, who was usually at Buckingham Palace or at Windsor.

But they were reunited at the Berkshire castle for their safety after Philip was flown there by helicopter last March ahead of the UK’s coronavirus lockdown.

He made his last public appearance in July 2020, handing over his title of Colonel-in-Chief of The Rifles, a title he has held since its formation in 2007.

Earlier this year, he spent a month in King Edward VII hospital in central London before being discharged in March after being treated for an infection and, then, a pre-existing heart condition for which he was treated at St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

At that time the Queen sent a loving, albeit subtle message to her husband of 73 years, wearing the same diamond brooch she wore on her engagement announcement in 1947, during a webinar encouraging people to be vaccinated.

By the time of his death, Philip had become the longest serving consort of a reigning British monarch and the oldest ever male member of the British family. He played his role with unswerving devotion; by his retirement in 2017 he had attended 22,219 engagements in his own right since 1952, and attended thousands more with the Queen.

The royal couple celebrated not only their golden and platinum anniversaries but, in 2002, the Queen’s Golden Jubilee and her Diamond Jubilee 10 years later. On that last occasion, with his typical devotion to duty, Philip insisted on standing for hours in pouring rain for the Jubilee Pageant on the Thames, despite suffering acute pain from a bladder infection – for which he was later hospitalised.

If the Queen has only rarely shown emotion in public, Philip was been equally reticent with his affection. Early on in their marriage, Mike Parker noted with frustration that Philip never displayed his love for his wife. “I always wanted to see him put his arms around the Queen and show her how much he adored her,” he said. “I mentioned it … but he just gave me a hell of a look.”

On millennium eve, Philip finally relented. In front of thousands of people at London’s O2 Arena, he turned to his wife and planted a kiss on her cheek. Then they linked arms and sang Auld Lang Syne with the rest of the country.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout