US powers ahead in world battered by geopolitical storms

For all the criticism of President Joe Biden’s style, he deserves credit for ending the year with the US in a strong position and for the risky move of playing hardball with Russia.

However fair that assessment then, the Biden administration has successfully navigated a difficult set of economic, political and international circumstances.

For all the criticism of the President’s style, he deserves credit for leaving the US, at the halfway point of his presidential term, in a relatively strong position that can only enhance Australia’s security, too.

Russia, China and even the US’s “frenemy”, the EU, have had a shockingly bad year.

The risky move to play hardball with Russia, contrary to the previous conventional wisdom espoused by everyone from Obama to Henry Kissinger, over its invasion of Ukraine has proved a geopolitical masterstroke.

Republicans have begun to chafe at the billions of dollars being sent to Kyiv, but standing with Ukraine has paid huge dividends for the US economy and international standing, whatever the moral imperatives.

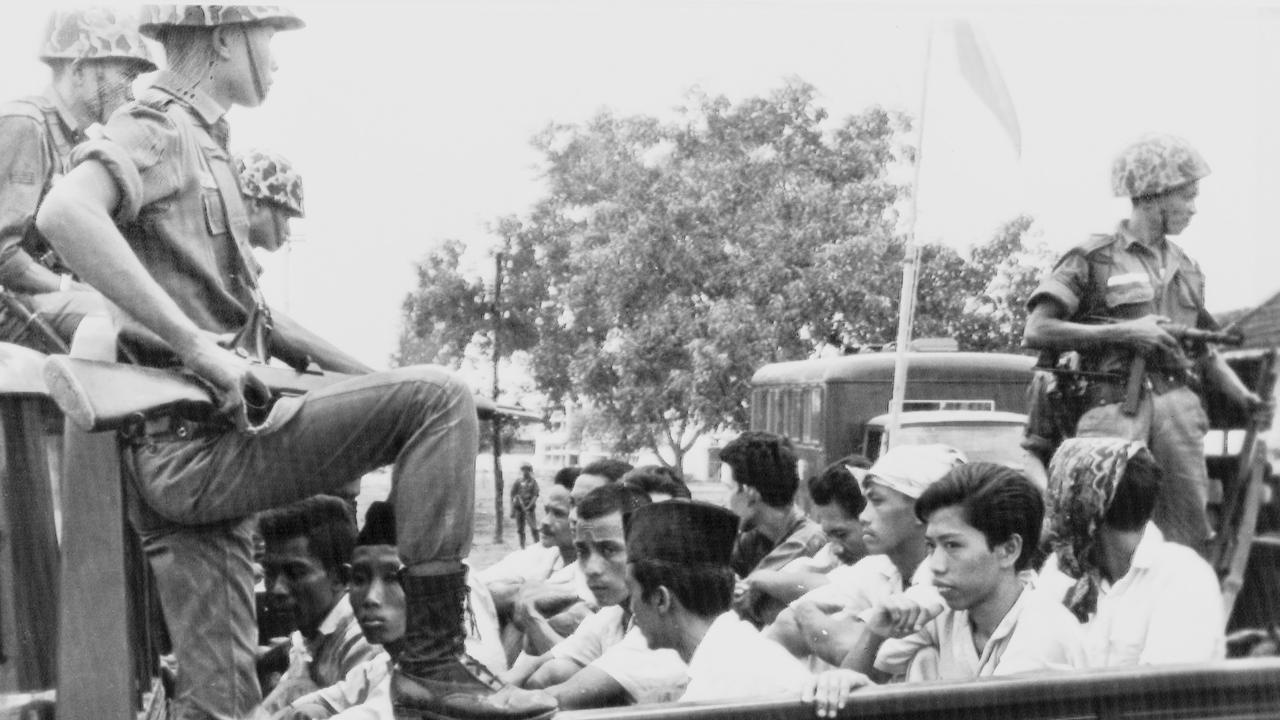

The US spent more than $US2 trillion on its war in Afghanistan, which it lost, and achieved very little. The ledger for Vietnam in an early era was even more embarrassing.

But compare that with Ukraine. According to the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, the US had given $US68bn ($100bn) in aid, mainly in the form of military support, as of late November. Even once the extra $US45bn that was legislated by congress this month is factored in, this is small change for the US budget.

Russia’s supposedly mighty military, even if it ultimately prevails owing to proximity, has been humiliated without the loss of a single US soldier. As an advertising campaign for Russian hardware, Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine has been a disaster.

Nowhere is US pre-eminence starker, though, than in relation to Europe, which has shrunk to almost vassal status. The euro currency is the symbol of the EU but ever closer union was always first and foremost a political project: a way for France to tie down an economically more powerful Germany, for Europe to expert an independent foreign policy of Washington.

Instead, the EU, Paris and Berlin have implemented US-designed sanctions, contrary to their own economic interests. France vetoed the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and it’s hard to imagine such feisty independence 20 years later. Charles de Gaulle would be turning in his grave.

Britain is on the precipice of a fiscal crisis, borrowing vast sums to insulate Britons from skyrocketing energy prices. A tripling of gas prices is driving European manufacturers into the ground – or to the US. Germany’s prized chemical and car industries, among others, will struggle to survive at current energy prices. Industrial giant BASF has signalled it intends to move operations to the US.

American liquefied natural gas exports to Europe are soaring, and the prospect of a prolonged war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia that are likely to last perhaps decades means higher prices will become a permanent ball and chain on European industry.

The hundreds of billions of euros European nations are borrowing to shield households from higher energy costs cannot alter this new harsh economic reality.

And whoever blew up the Nord Stream pipelines did the US an extraordinary favour, as Secretary of State Antony Blinken said earlier this year. Germany, even if it wanted to, cannot easily fall back on the cheap Russian gas that powered its manufacturing powerhouse.

As for China, its economy has slowed rapidly, its population is ageing and shrinking, and its “president for life” Xi Jinping is a diminished figure after his zero Covid debacle. The Celestial Empire’s working age population is shrinking. America’s is growing rapidly, and the world’s smartest people are still champing at the bit to migrate there. China’s business sector increasingly is guided not by market forces but by the political imperatives of Beijing, a recipe for long-term sclerosis if history is any guide. China could suffer the same fate as Japan in the 1990s; even as Japan was imploding, experts were pontificating about Japanese world economic domination.

The US economy has proved markedly resilient too, defying the nay-sayers who have continually predicted recession for most of this year. Gross domestic product grew almost 3 per cent in the third quarter, at an annual pace, compared with a pathetic 0.3 per cent in the euro area.

The Federal Reserve has ratcheted up interest rates faster than any time since the 1980s, but US households and businesses have powered on. Petrol at the bowser is once again cheaper than when Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine in February. Consumption, about two-thirds of the US economy, remains strong, and higher rates haven’t yet clobbered the US housing market and car sales, which typically depend on cheap credit.

While it is early days, inflation appears to have turned a corner, falling to 7.1 per cent across the year to November from more than 9.1 per cent in June.

If the US can onshore sophisticated chip and semiconductor manufacturing, it won’t even need to fret so much about Taiwan.

More important, US households, businesses and financial institutions, according to surveys and market prices, expect inflation to fall back to about the US Federal Reserve’s target of 2 per cent. For all their faults, the public still has confidence in their central bank.

The biggest risk in 2023 is China moving to help its new best friend, taking the place of Iran and North Korea, and sending munitions to Russia to help it save face. The US has warned Beijing any assistance would prompt a swift response, perhaps ushering in a vast trade war the likes of which the world has never seen. The workshop of the world entering a trade war with the world’s richest nation would usher in extraordinary turbulence.

But for now US success, economic and political, has buoyed Australia’s prospects; our defence increasingly relies on Washington’s good graces and the prospect of nuclear-powered submarines. The US will start 2023 on a high. For Australia’s sake, and the free world’s, let’s hope it ends it on the same note.

Bob Gates, former defence secretary under presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, once uncharitably remarked that Joe Biden had been wrong about every major foreign policy issue during his long tenure as a senator and then vice-president.