Why Melania Trump is giving everyone the silent treatment

The first lady was so inscrutable that Ivanka Trump called her The Portrait. Yet the power she wields doesn’t require words.

A chaste kiss on the cheek for his wife, Melania, at his victory speech in West Palm Beach, Florida, was Donald Trump’s tribute to the person who enabled him, perhaps more than any other, to reach the White House for a second time. It slipped off her smooth non-stick cheek.

Moments before, he had turned to his 54-year-old wife, flanking him on the stage, boasting that her memoir, Melania, was the No 1 bestselling book in the country: “Can you believe that?”

It is, compared to many unmentionables invoked by Trump in rally mode, believable. When Trump first took office in 2017, Melania was memorable for her absence. Compared with the close political alliances within the marriages of the Clintons and the Obamas, that spousal advisory position was, in the Trump hierarchy, supplanted by Melania’s stepdaughter Ivanka. Melania strangely resisted moving into the White House for months, and frequently bowed out of accompanying her husband on official events.

This is a book written from the perspective of a wife with icy loyalty to her husband, despite him talking about grabbing women “by the pussy” in 2005 at a time when Melania was pregnant with their son, Barron. Or despite him being convicted in a case of fraud this year, involving hush money paid to the porn actress Stormy Daniels. A porn actress who Trump had an encounter with in 2006, a few months after Melania gave birth.

A woman with immense power, whose departure from Trump, whether or not she released kompromat, would have neutered his political ambitions. A woman with immense power only matched by hostility to self-revelation, despite what it cost her in likeability, who finished her tenure in 2021 as the least popular first lady yet, according to surveys by CNN, SRSS and Gallup. A cold war queen with the power of checkmate: who wouldn’t want to read a book - published in the UK today (Thursday) - telling that story?

Especially now that, while this has been Trump’s third run at the presidency, for Melania, with her son at university in New York and Ivanka off the political scene, it may feel like her first run at first lady. Especially when Melania, as an immigrant, and a woman, and someone who believes in a woman’s right to abortion but is prepared to put that aside to tie her fortunes to Trump, embodies exactly the voter her husband needed to stage his incredible comeback. Especially as her private persona is so crucial to the development of his public one.

In 2012 Melania posted a stock photo of a beluga whale, in which she seemed to find kinship. The whale has frozen, glossy skin, and no clues to its intellect. Melania captioned the post: “What is she thinking?” Trump may be famous for bloviating, but this book promised to blow out the whale’s story.

Now I’ve read Melania, I can reveal that it does and it doesn’t. There is no mention of “locker room” boys talk or porn stars. In keeping with Melania’s uncanny computer-generated quality - she had “Instagram face” before Instagram - it feels written by an AI bot instructed to flatter (whether she had assistance in the writing we don’t know, the book has no acknowledgments). It tells a heroic story of her success and blamelessness.

For example, a photographer early on allows “my natural beauty to shine through”. Is she being factual (she was a model after all) or vainly insecure? Later, as first lady, she visits a man who has been shot in the leg in a mass shooting in Las Vegas. Despite this, he wants to stand up for her. “It’s my honour,” he apparently says. Everyone in her life, from herself to her son, her parents and husband, is described in never less than superlatives and she admits no mistakes.

The book is free of intentional jokes: at most there’s an occasion at their wedding when, Melania says, Billy Joel “humorously” substitutes lyrics in The Lady Is a Tramp to mention “Trump”. But sometimes the humour seems ready for the taking. On the morning of his first election victory in 2016, Melania recalls Donald turning to her before he went to work in his office, saying, “You’re first lady. Good luck.”

She is confused, almost as if there is a language barrier to her native Slovenian. Melania at first worries that her husband is being sarcastic or dismissive. “I looked at him, momentarily unsure of his meaning. Good luck? I realised he wasn’t worried, he was proudly confident I could handle the future.

“It was his unique way of saying ‘Good luck, I know you’ll excel, let’s get started.’ Donald had always placed a considerable amount of trust in me as wife, mother, confidante and advisor. That morning his trust felt particularly tender and profound.”

Yet, despite herself, an intriguing portrait leaks through. The Art of Her Deal, a biography of Melania by Mary Jordan, a journalist for The Washington Post, says that Melania spoke so little that Ivanka, when she was younger, nicknamed her “The Portrait”. In a rare interview, Jordan pressed the first lady for “the correct description of you”. Melania replied: “I know what I want, and I don’t need to talk.”

Melania inadvertently explains that behaviour, and explains for me the mechanics of her marriage. It was often assumed that Trump was the macho patriarch, while Melania was the feminine maternal figure, nurturing Barron. After all, Melania writes in this book that she “has long upheld traditional gender roles”.

Yet in their marriage these gender stereotypes are reversed. Trump is known to be a “charisma” politician, meaning it matters less what he does than how he emotes. He can range from logorrhoea to emotional incontinence, he relies on creating reactions. In a woman it would be enough for a Victorian doctor to diagnose hysteria: this emotional lability is stereotypically feminine. Meanwhile, Melania is the traditionally masculine strong, silent type.

Throughout the book she repeatedly reiterates her craving for order, organisation, planning and punctuality (the word “organisation” appears a dozen times). She also repeatedly talks of her tendency to solitude and her ability to survive without friends or socialisation. Her attempts at communication are so often misunderstood.

She infamously wore a jacket emblazoned with the words “I really don’t care, do u?” on a visit to migrant children. She says in the book that the jacket slogan (which could stand as her book jacket too) was “discreet yet impactful”, a subtle message to the media that she was indifferent to their negativity. We regularly see examples of her “systemiser” mindset, confounded by the messy human world.

In all the passages of her early life until she reaches New York at the age of 26, she never once mentions friends. By contrast, she notes her older sister “made friends with ease”. Thereafter, she mentions unnamed friends infrequently. There are no bridesmaids at her wedding. Instead, her description of her early years focuses on the interior design of her childhood flat, and the elaborate cake decoration supplied by their nanny, a focus on interiors and formal table decoration that intensifies in the White House.

If this was an introspective Barack Obama writing a memoir like Dreams From My Father, she might linger to analyse the physical and career resemblances of Donald to her father, a successful businessman.

But Melania has different pains: “Young people can be so dismissive towards anyone who is different in any way.” The “mean kids” are “cruel” to her, behaviour that she says would be described as bullying today. She “often found myself navigating the world on my terms”. She found “solace in my family or my own thoughts”. She persisted in her “methodical mindset”, and comforted herself by saying the jibes were “their problem, not mine”.

She describes herself as having “organisation, orderliness and a methodical approach”; she is a “methodical wife”. She develops a “profound knowledge of the mechanical and technological aspect of cars”.

At college she at first specialises in industrial design, appealing for its “discipline and structure”. She becomes frustrated when waiting to take residency of the White House because she cannot get access to measure the rooms. Thereafter her passion - seven pages are devoted to the subject - is for interior renovation.

In the photos in the book she is often pictured alone in White House rooms, with her design for table settings or a new rug. This includes the creation of a luxury White House tennis pavilion: there is no mention of tennis. It is exteriors and interiors that house emptiness.

This neurotype complements that of her husband. She is the unchanging and strong rigidity that can support his looseness. She says at one point she seeks to emulate the first lady model of Jackie Kennedy, who she says is “flawless”.

Cultivating flawlessness is apparent in the attention paid in the book to her outfits: “Self-care remains a guiding principle in my life.” This flawlessness means she also does not like to be wrong. She describes several incidents, such as the plagiarisation of a speech by Michelle Obama or her unsuccessful beauty business, to land blame on others.

On the day of the Capitol riots she says she is deep in the White House with a team of photographers and designers, recording her beloved room renovations. Melania writes that she notices a “sizeable gathering” outside the window, but even despite an entreaty from her press secretary to “denounce the violence”, does not break off from her task (she later blames her staff for not keeping her fully informed).

Melania is far more interested in the look of American democracy than its substance. In this way the union of Donald and Melania is an inverse of The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. Melania remains flawlessly unchanging and unreactive, a self-described “perfectionist”, tucked away silently in an inner sanctum of the White House. In the balance of their relationship, this allows her husband, 24 years older, to be out in the world, enacting the uglier side of politics.

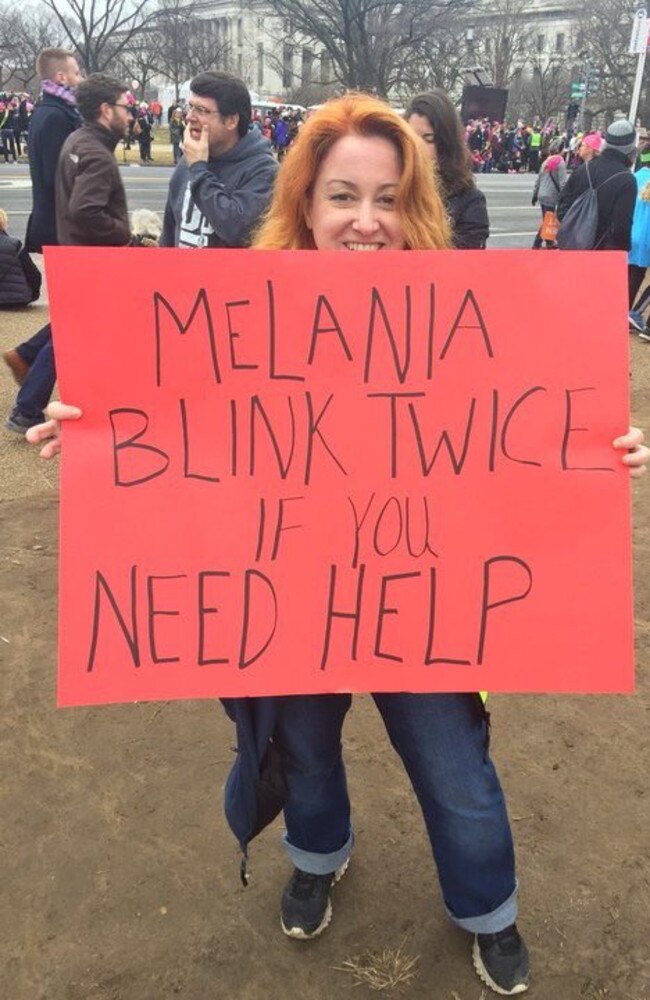

What this book and her new term as first lady serves as is a rebuke to being patronised. In 2016 there was a semi-serious story, peddled by the pussy-hatters at the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, that Melania was a kind of unwilling mercenary, a hostage even. Banners read “MELANIA: BLINK TWICE IF YOU NEED HELP”. To this day, conspiracy theorists imagine she has a body double. As soon as Trump’s power left him, this narrative went, so too would his third wife. This was infantilising. Melania is powerful, even if she does not always take responsibility.

According to the book by Jordan, Melania goes icy when furious. In 2016, at the crucial revelation of the “pussy-grabbing”, Trump gathered with advisers, focused only on the power of the woman 30 floors above them in the Trump Tower penthouse.

If she walked out, the campaign was over. Trump seemed frightened to face her and, according to Jordan, took two hours to step into the lift. In particular, Melania hated pity. “Don’t feel sorry for me,” she said in her next TV interview to CNN on the subject, saving her husband’s political career, “I can handle everything.”

From very young, Melania developed a self-preservationist way of editing out or wallpapering over her life’s unattractive distractions. She praises her husband in this book as the “unity” candidate. She also - shortly after a speaker had referred to Kamala Harris as the “antichrist” - talked of “unity” at his recent Madison Square Garden rally. We can hope that Donald Trump can be as stable in his governance as he is in his marriage.

The Times