Why did Justin Trudeau go? Inside Canadian PM’s fall from grace

He came to office with the same message and momentum as Barack Obama. Nine years on, that’s a distant memory.

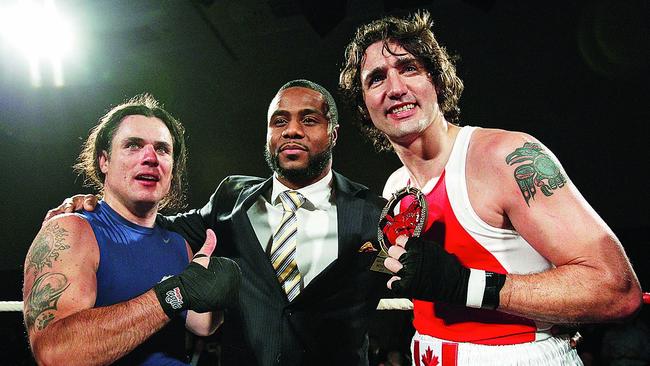

In one corner of the boxing ring, a lanky-looking Justin Trudeau, 6ft 2in, shifted nervously on his feet. On the other stood Patrick “Brazz Knuckles” Brazeau, a heavily tattooed Conservative senator and former naval reservist with a black belt in karate.

Going into the 2012 charity fight, Trudeau, an MP for a small district in Montreal, was considered the underdog, with bookies giving 3-1 odds against.

Trudeau, however, defeated his rival in three rounds.

The image of a victorious Trudeau made the cover of magazines and was said to have inspired the decision to launch a campaign to lead the Liberal Party and return it to power.

It was fitting, then, that on Monday Trudeau, 53, would frame the abrupt end to his near-decade in office in boxing terms.

“Every bone in my body has always told me to fight because I care deeply about Canadians. I don’t back down from a fight,” Trudeau said in his resignation speech on Monday, after months of pressure to step aside before this year’s general election.

That pressure had grown after Chrystia Freeland, his deputy prime minister and finance minister, resigned from his cabinet last month, and came amid the threat of tariffs from an incoming Trump administration, a worsening economy and dismal approval ratings.

The decision marked the end of a three-term rule of a leader initially hailed for returning the country to its liberal past. Trudeau, son of one of Canada’s most famous prime ministers, became deeply unpopular with voters who deemed him to have failed to deliver his promised “Canadian dream”.

Trudeau, 53, had built a brand as a progressive, a feminist, an environmentalist, an advocate for refugee and indigenous rights, helping him gain a global following dubbed “Trudeaumania”. Vogue ranked him as one of ten “convention-defying hotties” when he announced a 50 per cent-female cabinet.

With Donald Trump replacing Barack Obama across the border, Trudeau seemed to offer the western world continuity of Obama’s message of hope and change.

He had come to office at a tumultuous time, at the height of an emerging refugee crisis as millions of Syrians and others fled wars for a migrant trail across Europe. Despite warnings about the impact of increased immigration on housing and services, Trudeau welcomed three million new arrivals.

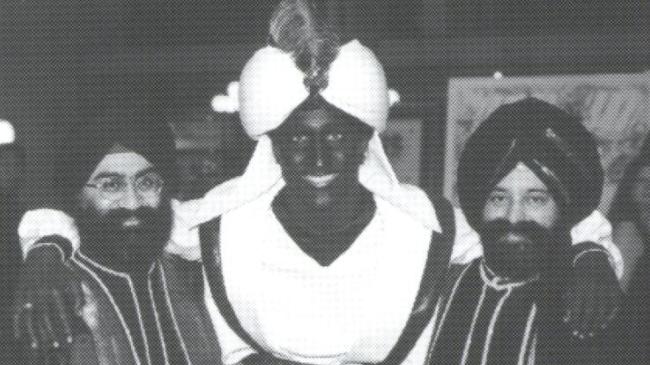

The honeymoon lasted four years before he was haunted by a 2001 photograph of him dressed as an Arabian prince with black face paint that went viral.

“I’m going to be asking Canadians to forgive me for what I did,” Trudeau told reporters. They ultimately did, but support began to wane. In 2019 and 2021, his party went on to lose seats in parliament in two elections, requiring him to form minority governments propped up by a left-wing opposition party.

Canada’s Covid-19 lockdown, one of the strictest in the world, left a long shadow on the country and led to nationwide protests.

In 2023 he separated from the “première dame” Sophie, his wife of 18 years and mother of their three children, who rekindled an old relationship with a paediatric surgeon from Ottawa and refashioned herself as a lifestyle guru.

Ethical lapses and controversies continued to erode Trudeau’s image. He vowed action on climate change, but bought an oil pipeline and walked back part of his signature carbon tax.

By this time, public anger had steadily grown. Inflation rose to historic highs, and the cost of housing in many Canadian cities became untenable. An economic analysis last year found that in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, prices would have to plummet, or incomes improbably soar, to restore affordability.

Trudeau was blamed for keeping emergency Covid fiscal measures in place for too long and a country once proud to be the world’s most welcoming host started to grow resentful of the continuing arrival of migrants.

“There [was] an increasing disconnect with the interests and preoccupations of most Canadians,” Richard Bisaillon, a political science professor at Concordia University in Montreal, said of a premier and a party he saw as no longer concerned with the kitchen-table issues.

Despite turmoil at home, Trudeau retained much of his global appeal. According to a YouGov poll from last year, he remained the most-liked politician after President Zelensky of Ukraine. Oliver Paré, a political commentator, called him “our happy face to the world” that masked deep discontent in Canada.

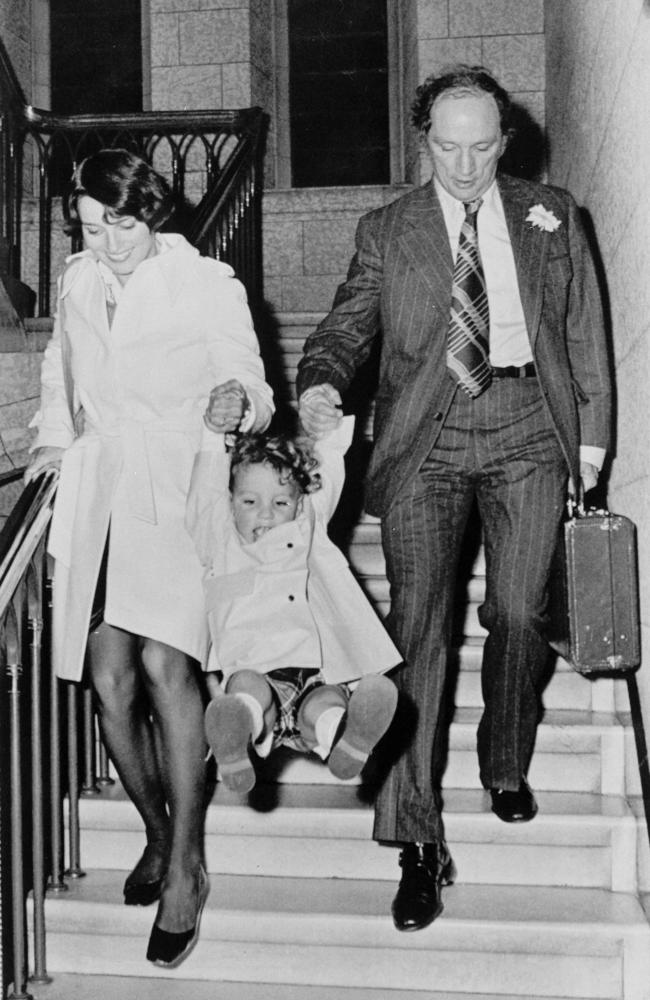

Trudeau’s rise was charmed. He was born while his father, Pierre, was in his first of four terms in office. President Nixon of the US foretold the younger Trudeau’s inheritance of the position when he toasted in 1972 to the “future prime minister of Canada” at a gala when Justin was just a few months old.

In his early adulthood, Trudeau worked as a nightclub bouncer, a snowboard instructor and secondary school teacher before running as a local MP and later leader of the Liberal Party.

Those who know Trudeau told The Times he was behaving like his father did in the dying days of his premiership, like a man “on a mission from God”. His chances for success looked slim. Polls suggested his party trailed the opposition by 20 percentage points, yet he clung on.

His allies doubted that he would step aside, as President Biden did, to give his party the best chance in the election. But Trump’s victory in November brought into sharp focus Trudeau’s weakened position. The president-elect threatened to impose blanket 25 per cent tariffs on Canadian goods, which Trudeau knew would devastate Canada economically. Trump had begun mocking Trudeau, referring to him as a “governor” of America’s 51st state.

Then, Chrystia Freeland, deputy prime minister and finance minister, resigned with a scathing letter, accusing Trudeau of engaging in “costly political gimmicks” and being ill-prepared to face the challenge posed by Trump.

He mulled his options over the holidays and came to the same conclusion his father did four decades earlier. Trudeau Sr took a now legendary solitary stroll in an Ottawa blizzard as he weighed up his decision to resign in 1984, after 16 years in power. The time had come for Trudeau Jr to take his own walk in the snow.

The Times