What’s in a name? The best actors forget their own

A study using brain-imaging technology has found that actors become so immersed in their roles that they forget themselves.

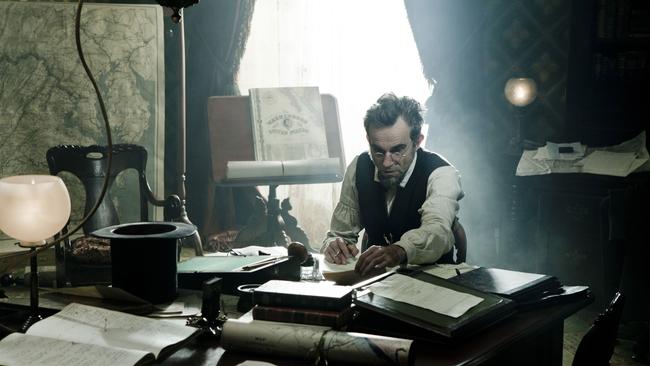

When he played a Native American in The Last of the Mohicans, Daniel Day-Lewis insisted on learning to skin a rabbit. When he played Hamlet, he quit after reportedly claiming to have seen the ghost of his father on stage.

And when he played Abraham Lincoln, fellow actors complained he signed letters “Abe”.

Method actor Day-Lewis, 65, might be an extreme example, but a study has suggested that he is not alone in losing his sense of who he is when acting.

In particular, scientists found that actors’ brains appear to respond less strongly to hearing their own name when they are playing a role.

This implied, albeit in a small study, that when they are acting, they are to an extent subsuming their very idea of self.

The finding relied on a phenomenon known as the “cocktail-party effect”. “What’s in a name?” asked Shakespeare. One answer is that a name is, neurologically speaking, “highly salient”.

So attuned is our brain to our own self that typically when we hear our own name – even across a crowded room – it locks on to the sound.

“As soon as somebody calls your name, even in the middle of a busy social event, you can pick that up,” says Dwaynica Greaves, from University College London. “This is true even to the point where if someone calls your name, maybe a couple of seconds after, you can be pulled up and think, ‘Did someone actually say my name?’”

What happens, though, she wondered, when you are trained to pretend to be someone else: “If we put an actor in character, and then they hear their own name called out, how would they respond?”

The answer, at least according to her pilot research into actors rehearsing A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is that their own name appears to lose its salience.

They still hear their name, but their brain no longer responds as if it is quite so special. According to Greaves’s findings, this response to your own name, universally seen in social situations, appears to be significantly lessened when actors are playing roles.

The results, published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, came about only because of new brain-imaging equipment that can be worn as a helmet. This means that people can wear it in more natural situations.

A major goal of Greaves’s study was to test out the equipment, and show it could give useful results in theatres.

But when analysing six actors, and comparing their brain’s response to hearing their own name when they were rehearsing and when they were merely reading out lines, the researchers came across an intriguing finding.

Consistently they found a part of actors’ brains in the prefrontal cortex responded strongly to being interrupted by their name only when they were reading out lines, as opposed to when they were actually acting. It was as if their name became less salient when they had taken on someone else’s name.

Greaves is keen to tease apart where it is that an actor’s own identity and that of their character begins and ends.

An amateur actor herself, she says that being on stage requires both being in and staying separate from the part. “You have to be aware of your surroundings. If water spills on stage, you have to be aware not to walk and slip on the water,” she says. “You are the character, but at the same time, you are still yourself. How do you balance that?”

THE TIMES