What we’ve learnt about chess from The Queen’s Gambit

What does the hit Netflix drama The Queen’s Gambit get right – and wrong? Two experts weigh in on the series helping to make chess sexy again.

It is the surprise hit of the season. The Queen’s Gambit, a seven-part Netflix adaptation of a 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, has helped to make chess sexy again. Or, quite possibly, sexier than ever. It has been Netflix’s most watched show for two weeks and counting. What’s more, Anya Taylor-Joy’s performance as Beth Harmon, the orphan from Lexington, Kentucky, who goes on to challenge the best players in the world, has had an immediate effect on how chess is seen.

The website chess.com, which has praised the series for “getting chess right”, had already been getting three times as many new members as usual during the pandemic, according to its director of business development, Nick Barton. Since The Queen’s Gambit started streaming on October 23, however, its membership has been growing faster still: 480,000 new members last week alone. “Seemingly each day since the show’s release we’ve been setting a new record for members joining the site,” Barton says.

Chess matches are back on television too. Last week Eurosport signed a deal to broadcast coverage of the Champions Chess Tour – the first professional online championship – from now until September next year. “Chess is definitely gaining in popularity,” says Jovanka Houska, the UK women’s chess champion. “I just spoke to a friend who had been interviewed by Vogue.”

The Queen’s Gambit’s adapter and director Scott Frank worked hard to “get chess right”. He recruited the chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini, who also advised Tevis on the novel, and the former world champion Garry Kasparov to help him. And yet the show is very much fiction. Its protagonist, Beth Harmon, becomes a chess sensation in the America of the 1960s. In real life it wasn’t until 2005 that Judit Polgar of Hungary became the only woman to make it into the world’s top ten.

Yet the chess community has embraced the show. The Times’s chess correspondent, David Howell, 29, a three-time British chess champion who became Britain’s youngest grandmaster at the age of 16, is among its fans. He calls the chess scenes “well choreographed and realistic”.

Houska, 40, also loves The Queen’s Gambit. “I think it’s a fantastic TV series,” she says. “It conveys the emotion of chess really well.” And yet . . . we had to wonder . . . this is television. To entertain us, how many liberties has the series taken with what playing chess for a living is really like?

Do all top chess players have emotional issues?

Beth Harmon is orphaned, gets addicted to the tranquillisers they give her at the orphanage . . . and the problems keep coming even after she gets adopted. She becomes a heavy drinker and struggles to find human relationships that rival her relationship with chess. Is this just a fictional trope? “I want to say yes, but there is a degree of obsession in every high-level athlete everywhere,” Houska says. “You have to have that if you want to go further. That is a big thing that distinguishes us from other people. But you have normal chess players who are interested in all sorts of other things too.”

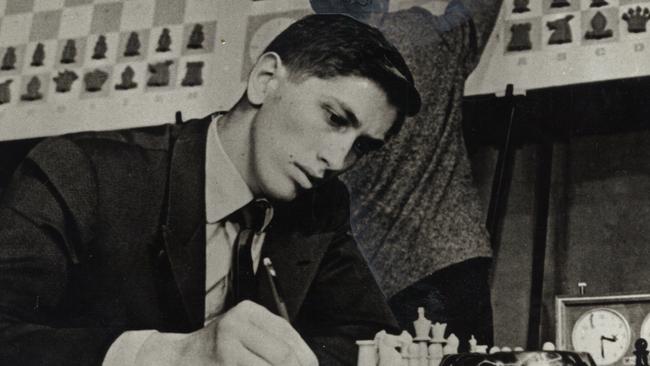

The character of Beth was partly inspired by Bobby Fischer, the American former world champion famous for his mental struggles and disruptive behaviour.

These days the top players are more likely to be micromanaging their sugar and caffeine intake than spiralling out of control. “In the levels below, though, there are cases of people who get lost in their own minds,” Howell says. “Some players drink, some players gamble. Chess players have addictive personalities, myself included, so I try not to drink, try not to gamble. It’s a slippery slope.”

Do all chess players have their own Obi-Wan Kenobi figure?

In The Queen’s Gambit Beth’s chess mentor is the janitor at her orphanage. In Howell’s case it was Jonathan Tuck, a chess coach who spotted him at a tournament when he was six, then coached him and travelled with him to tournaments “without asking for a penny”.

For Houska it was her father, Mario. “You need a mentor, it’s super-important,” she says. “My father wasn’t an Obi-Wan Kenobi, he just gave me no choice: ‘This is a family game and you’re good at it, so carry on.’ Everyone has had some sort of inspiration like that.”

Can chess earn you good money?

Beth starts making a living from her playing while still a teenager. In real life, Houska says, it’s hard to survive on prize money alone. “To earn a comfortable living you really need to be top twenty, maybe top ten in the world.”

Some countries, such as India or the US, have well-funded chess federations that can support their players. “In western Europe it’s very tough,” Houska says. “Most professionals I know are making their livings from coaching, commentary, writing books.”

How much does Howell earn from tournaments? During the pandemic, he says, nothing: the British Chess Championships, for example, were cancelled this year. Normally, prize money will be about half of his income. For other top British players prize money might be as much as “80 to 90 per cent of their income. That is a lot of pressure.”

Can chess really be that glamorous?

Chess takes Beth from Kentucky to tournaments in Mexico City, Paris and Moscow. Nice hotels. Swish dinners. In reality, Houska says, chess is a game of extremes. “You can play in the most glamorous five-star hotel one day, be crammed in with 80 other people in the dingiest school room the next, being forced to share the toilets with the men. That is the worst.”

Is chess really a hotbed of romance?

Beth locks eyes with more than one fellow chess player in The Queen’s Gambit. In real life it’s only the biennial Chess Olympiad, where five men and five women from various countries turn up to compete, where talk of zugzwangs and Sicilian Defences is likely to extend to pillow talk. “It’s one big celebration, in a good way,” Howell says. “They are all very serious about the chess, but in any profession there are situations like that where stuff happens.”

Howell, who is single and lives with his family in Seaford, East Sussex, prefers not to go out with chess players. He’d rather switch off from the game. That, Houska says, is quite rare. She lives in Bergen, Norway, with her husband, Arne Hagesaether. He works in IT in the shipping industry, but they met while competing in a tournament. “Most couples are formed within the chess community,” Houska says. “Rather uniquely, Arne is quite a bit lower-rated than me.”

Do chess players really help one another out?

In The Queen’s Gambit Beth’s rivals go on to become her training allies. Really? “I used to try not fraternising with the enemy,” Howell says. “But as I’ve got older I’ve realised that, actually, unless you are in the World Championship finals or something, why not? I’ve been on training camps with some of the best players in the world, and they are very open about sharing their ideas.”

However, Houska says, British chess needs more funding to enable more teamwork like this: it’s the best way for players to go from good to great. “In other federations around the world, nobody believes in this lone-wolf thing.”

Do chess players really psych each other out?

Now and then players try to get into Beth’s head to disrupt her play in The Queen’s Gambit. Houska has seen elite chess players toy with their opponents, but it’s not something she recommends. “You don’t really want to expend any energy on psyching people,” she says. “You just want to focus on the game.”

Howell, however, has had a couple of players deliberately kicking him under the table during matches – and worse than that too. Once, when he was a junior, he was in a final he badly wanted to win. Yet the night before people kept ringing his phone and knocking on his hotel door then running away. He later discovered that it was friends and family of his opponent. He lost the match. “I barely slept. I was broken, psychologically.”

Do male chess players patronise female chess players?

More than we see happen in The Queen’s Gambit, Houska says. Yes, the grumpy janitor first expresses disbelief that a girl could play chess. A few local types underestimate or patronise her. After that, “Beth has it very easy, really. Everyone shows her respect.”

Meanwhile, Houska has had senior male players undermining her while she is doing presentations, or ganging up on her in tournaments, deliberately playing slowly in their games with her in an attempt to exhaust her. “That takes its toll,” she says. “And when you are young you get the constant comment that girls can’t play chess. Boys are very good at shouting girls down. And this is a problem because there aren’t so many girls playing chess. They become timid, they say, ‘Oh, OK, I’ll back off because this boy sounds very confident.’ ”

Does chess really happen at such speed?

Part of the appeal of The Queen’s Gambit is the way the matches happen so fast, players’ fingers dancing between chess pieces and chess clock. Championship chess is more deliberate, Houska and Howell say, even if it has speeded up a lot since the seven-hour matches of the 1960s.

Beth’s games happen more at the pace of “blitz” chess, which gives each player a total of three minutes’ playing time plus two seconds per move, or “rapid” chess, which is 15 minutes per player plus ten seconds per move. “Beth is playing abnormally quickly,” Houska says. “At that speed you don’t have time to process all the thoughts and plans.”

Could a woman become the best player in the world?

No reason why not. “It is very hard to explain why there has been only one woman who has made it to the top ten in the world and only one other [Hou Yifan of China] who has made it to the top 100,” Howell says. “I am optimistic it will happen one day. In the past the small participation numbers by women has made it hard, probability-wise. Hopefully this show will inspire more young girls to play.”

The real issue is social, though. “I want, before anything, for chess to be fun for girls to play,” says Houska, who captains the England women’s team. “And to do that we need to increase the numbers. We play online; it’s just to form a community, get the social side going, all to reinforce the idea that chess should be fun. And then once we’ve done that we can cater to all the levels. So that if a girl wants to be a Beth Harmon, there’s the right support network for her. I want it to be a level playing field. Until we get to that stage I don’t think we can talk about biological or genetic disparities.”

(The Queen’s Gambit is on Netflix)

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout