Westworld and streaming TV’s never-ending stories

Spare us storytellers who don’t know when to stop and have no idea where they are going.

The best thing about the World Cup was that every night the soccer gave us something to watch. It was simple; there was drama. Each evening that epic in Russia offered us another 90 minutes of thrills. Sometimes, if there was more story to tell, it went to 120 minutes, then penalties, but still it was concise and finite. A narrative began and ended. How on earth are we meant to go back to Westworld now?

That television series about an android amusement park gone wrong — based on a tight 88-minute film from 1973, itself based on a slim novel — has just wrapped its 20th episode. That adds up to 1266 minutes so far, including two finales as long as the original movie; yet, despite that, small-screen Westworld has managed to tell less story than its source material did. Some achievement. The show meanders with no sense the writers know how to end it, and it comes as no surprise that the series has shed 680,000 viewers in America in the past 18 months. It is symptomatic of its medium. Is it that, in an uncertain world, we don’t want uncertainty as entertainment? No. People are just tired of indulgence.

Last month, the actor Ethan Hawke told me he has turned down plenty of TV because it never knows what it is doing with itself. “Here’s the trouble,” he said. “What I enjoy about acting is being a storyteller, having a beginning, middle and end. The trouble with most television is it doesn’t have that. Most shows feel like they’re wandering to entertain you. I struggle if people send me pilots. I ask what the point is and they say, ‘You’re not going to know until season five.’

“I’m never sure these guys know where they’re going, and it’s impossible for filmmaking to be deliberate if nobody knows what the point of the story is.”

The vaunted “golden era” of TV has lost its shine. That name was given to the first decade of this century, when acclaimed dramas such as The Wire, The Sopranos and Mad Men had one authoritarian showrunner who knew precisely where their story was heading. Being generous, we’ll call what we have now the Bronze Age: a time when there is huge choice, but nothing can claim culture’s focus like a great series used to.

Partly it’s because, with so much on offer, it is easier to feel bored and distracted, and move on. But patience is key, too. It is hard to devote yourself to a relationship you think might outstay its welcome — and don’t most TV shows these days? “That’s why I’ve always been drawn to movies,” Hawke concluded.

The problem here is that, like TV, films have grown longer, frequently “wandering to entertain” in meagre plots spread over the entirety of a two-term government. Yes, most resolve those plots by the time the end credits roll, but the art of quick stories has receded.

In 1931, the average running time of a film was around the 90-minute mark, whereas this decade it is more than 120 minutes. Is that added half-hour necessary? Did Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong remake really need 187 minutes — 200 in the special edition! — when he was pretty much telling the same story as the 1933 original, which ran to 100 minutes?

Thanks, Peter, that’s an extra two hours of babysitting. No wonder I’ve never seen all 462 minutes of his bloated take on The Hobbit, the biggest fuss made over something small since the heyday of Prince.

Superhero blockbusters with umpteen characters to fit in have long needed to be long. Without its 149 minutes, how could Avengers: Infinity War offer decent backstories for its 27 principal roles? The problem for people with other things to do, though, is that, away from the silliness of summer cinema, there is a sense that length equals seriousness in award-worthy films. It is rare to have an Oscar winner less than two hours long.

Partly, both indie and studio films go large as they fear losing market share to home entertainment and believe value for money in cinemas is proved only via chest-pumping displays of bombast.

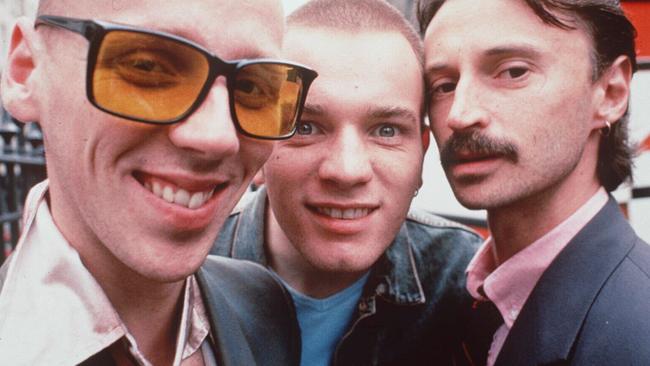

It’s ridiculous when you consider that Before Sunset is 80 minutes long, Reservoir Dogs a breezy 99, Gravity a trim 91, Lady Bird a waste-free 94, Men in Black a sprint at 98, Casablanca a tidy 102 and Trainspotting a decade-definer despite being only 94 minutes long. These are what we’ll call World Cup films, ones that reach a resolution at a decent length. Ones that, like Belgium v Japan, know we have busy lives, so wrap up before we get bored, or sore.

It’s no surprise the most buzzed TV dramas this year, Love Island aside, have been Hugh Grant’s A Very English Scandal, about politician Jeremy Thorpe, and Benedict Cumberbatch’s Patrick Melrose, based on Edward St Aubyn’s novelistic memoir about addiction and abuse — three and five episodes respectively.

Patrick Melrose could easily have done a Handmaid’s Tale and bloated out beyond the books, but it stuck to its key theme, the horrific treatment of a child and the heroin that followed, and Cumberbatch’s face could imbue every scene with depth. He knew where he had come from and where he was going. The actors in Westworld don’t even know if they’re human or robot.

The concern for people who enjoy entertainment that doesn’t base its span on the duration of a transatlantic fight — and back again — is that its length is going to get longer. On Netflix and Amazon, where there is no scheduling grid based on hour and half-hour program lengths, anything can be done with running times. That can lead to a show like The OA (2016). A confusing drama about, well, nobody knows, it had huge variations in its episode lengths. Some ran for more than an hour, others for 30 minutes.

Granted, this is a new freedom for creators, unshackled from ad breaks and, say, the news. That is partly why Charlie Brooker took Black Mirror to Netflix. The more writers realise they can be more flexible elsewhere, the faster they will flock there, which means more traditional channels will need to follow suit or lose talent. Yet talent is often egotistical. It rarely thinks restriction is good.

Hence, HBO allows Westworld to be whatever Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy want it to be. If they didn’t, the writers would move the show. Maybe it will never end. Or maybe the viewing figures will force a backlash against plots that talk a lot, but don’t say anything of note.

Here’s hoping, because we are heading for a viewing future that is the equivalent of question time in parliament: no sense of control and an awful lot of hot air.

THE SUNDAY TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout