Unravelling the mystery of how sex offender Jeffrey Epstein made his millions

Convicted sex offender and college dropout Jeffrey Epstein left $747 million when he took his life. Was he a financial genius or was there more to it?

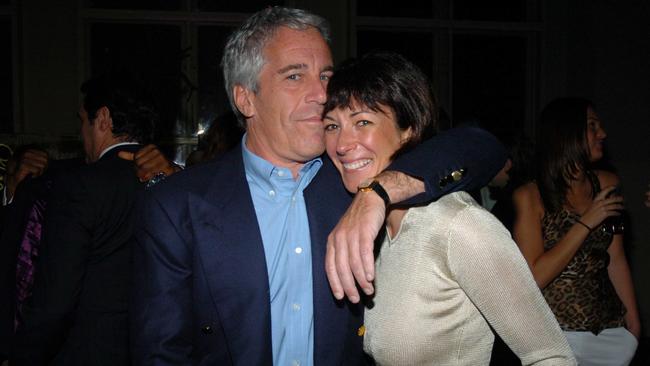

All kinds of spectacular conspiracy theories were born when Jeffrey Epstein died. Here was a hugely wealthy man who was friendly with a variety of rich and famous people. He was charged with sex trafficking minors. What did the rich and famous people know of this? Would the trial have exposed them somehow? Epstein had boasted to a journalist that he knew compromising things about many of them. Now, conveniently it seemed, he had taken these secrets to his grave.

Tangled up in these unknowns was another, more basic question. How did a chap from Brooklyn with a rather sketchy CV wind up with an estate worth $US578 million ($AU747 million)? A week after he took his life in a Manhattan jail in 2019, a will filed with a court in the Virgin Islands listed his assets: $US56 million in the bank, $US322 million in stocks, bonds and investments, palatial homes in New York, Paris, New Mexico and Florida, a private island in the Caribbean and a fleet of planes to zip between them.

How did he get all that? This fellow didn’t even finish college. Plenty of college dropouts make it big, of course, but we can usually see how they made their money. How did Epstein manage it? To that question at least we now have the beginnings of an answer, courtesy of a thoroughly researched report by a Manhattan law firm that examined payments he received from a Wall Street billionaire named Leon Black.

A billionaire named Black

The investigation was spurred by a report in The New York Times last autumn claiming that Black paid Epstein at least $US50 million and perhaps as much as dollars $US75 million between 2012 and 2017 for advice on his finances. This, to a man with no formal training in tax and estate planning and who had just served prison time in Florida for “soliciting prostitution” from a teenage girl.

In the ensuing uproar the hedge fund that Black co-founded hired the Dechert law firm to do an independent investigation. This revealed that Black had paid Epstein $US158 million over five years. He also lent him $US30.5 million, of which Epstein paid back only $US10 million.

What on earth was going on here? The authors first address the elephant in the room. They saw no evidence that Black was “involved in any way with Epstein’s criminal activities”, they write. “There is no evidence that Epstein ever introduced Black, or offered to introduce Black, to any underage women.”

Black apparently told them that he had known Epstein since the 1990s and wasn’t fully aware of the gravity of the allegations against him. He said that he believed in giving people a second chance and was reassured by the fact that so many famous, powerful people still dealt with Epstein in business, or socially: “CEOs, banking institutions, leading figures in technology, science and business, diplomats and Nobel Laureates.”

Helping rich avoid taxes

What was in it for Black, or indeed for some of these other very wealthy people? According to the report, Epstein was very good at helping phenomenally rich people to avoid taxes. They say that they interviewed 20 people, including Black, colleagues from his hedge fund and people who work or worked in Black’s “family office”, managing his $US9 billion fortune.

The witnesses generally agreed that “not all of Epstein’s advice was useful” and that he was “generally a disruptive and caustic force within the family office”. Yet many of them “believed that Epstein had creative ideas that no other adviser had proposed” and that he drove people to work harder.

And they believed that he helped Black to avoid, quite legally, a looming tax liability that might have cost him $US500 million, or perhaps as much as a billion dollars. “Black believed, and witnesses generally agreed, that Epstein provided advice that conferred more than dollars $US1 billion and as much as $US2 billion or more in value to Black.”

The fixer who found new cavities

Parts of their portrayal of Epstein align with earlier accounts of how he operated. It seems that he was quite good at inserting himself into the financial affairs of very wealthy people and finding problems they didn’t know they had, which they needed him to fix.

Black compared him to a dentist who kept finding new cavities in his mouth. He got tired of Epstein’s long emails identifying “long lists of perceived issues and problems”, the authors write, but he still felt that the cavities needed filling and that Epstein was the man for the job, even if he wasn’t actually a dentist.

“Although Epstein had no formal tax training, witnesses agreed that he was very knowledgeable on a variety of issues relating to tax planning, tax compliance, and managing and responding to audit inquiries,” the report says.

Epstein did apparently get some solid schooling: his father, who worked for the city parks department, is said to have been a big believer in the value of education. Although Epstein never got a college degree, he was good at maths and started teaching at a prestigious private school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

A tutor who landed a bank job

There he tutored the son of the chairman of Bear Stearns and impressed the father enough to land a job at the bank. He was doing reasonably well there until the spring of 1981 when he left, abruptly. By Epstein’s own account, he then went into business managing the assets of the wealthy, boasting that he only worked for billionaires, although the only such client whom reporters could find was Leslie Wexner, the founder of a retail empire that includes Victoria’s Secret.

“I think we both possess the skill of seeing patterns,” Wexner told Vanity Fair in 2003. “But Jeffrey sees patterns in politics and financial markets, and I see patterns in lifestyle and fashion trends.”

The magazine reported that Epstein had inserted himself so thoroughly into Wexner’s financial affairs that at one point Epstein was appointed, in place of Wexner’s mother, to the board of the family foundation. It also found that Wexner had bought, through a trust, the colossal townhouse — said to be the largest in Manhattan — in which Epstein lived and which was eventually listed as part of his estate. I remember going there once to knock on the door. The door is 4.5 metres high: it looks like the entrance to a castle.

The 2003 Vanity Fair profile, by the investigative journalist Vicky Ward, turned up the outlines of scandals in his past that were not quite proven. Ward found that Epstein’s sudden departure from Bear Stearns coincided with an insider trading controversy there. She found that after Epstein left the bank he worked with the head of a debt agency who was later imprisoned for a Ponzi scheme.

Ward has since said that she also uncovered evidence of sex crimes, interviewing two women who said that they were sexually assaulted by Epstein, in one case when the accuser was a minor. Their allegations were cut from her story. Her editor, Graydon Carter, has said he did not have enough proof to publish them.

Two years after the profile was published the Palm Beach Police Department in Florida, where Epstein had a waterside mansion, received a complaint from the parents of a 14-year-old girl who said that Epstein had paid her for a massage. They began an investigation. The FBI got involved and drew up a 60-count indictment, but Epstein and his legal team managed to negotiate a plea deal in which he pleaded guilty to lesser state charges, serving only 13 months.

Jail, then back to high society

Upon his release, Epstein returned to the good graces of New York high society. He began giving money to universities. Apparently this is when Black, the Wall Street billionaire, began seeing him socially once more. The two men “attended social events together, Black confided in Epstein on personal matters and Black introduced Epstein to his family”. Visiting Epstein’s home, he would meet other businessmen and famous political figures, “diplomats, scientists and celebrities”, the report says.

Epstein had told Black that he had been prosecuted for getting a massage from a 17-year-old prostitute, who had shown him a false ID, according to the Dechert report.

In 2012 the two men drew up an arrangement for Epstein to work on Black’s finances. Epstein told Black that he usually charged people dollars 40 million a year for advice, but would do it, initially at least, for $US23.5 million. Later Epstein apparently felt that he was underpaid. Taking credit for helping Black to avoid a $US500 million tax liability, Epstein said that it was really $US600 million and that he deserved a 10 per cent cut of the savings: a $US60 million payment. In the end they agreed to $US20 million for that piece of work.

Plenty of people must have been startled at the scale of these payments to a man with no qualifications. “It would be quite surprising to me if this man Epstein actually had skills that differentiated him from so many other people who are well trained,” a New York financier and former hedge-fund manager told me. He felt that Epstein “ran an extraordinarily successful extortion game with all these powerful people who came to his place and were filmed”. He paused a moment. “That’s just speculation of course.”

‘Blackmail videos’

In a documentary released last year some of Epstein’s accusers made the same claim more boldly, saying that he had cameras all over his homes that he used to make “blackmail videos”. There’s no evidence or suggestion of this in the case of Black, who announced plans to step down as chief executive of the Apollo hedge fund after the report was published, while remaining as chairman.

The authors of the Dechert report don’t even say the word, although there are moments when they allude to the idea. In emails to Black, Epstein would “invoke his friendship … including by referencing personal matters that Black had shared with Epstein in confidence”, they write, “although there is no evidence that those matters had any relationship to any of Epstein’s criminal activity or to any of Black’s payments to Epstein”.

The hedge-fund manager felt that “sometimes powerful people in finance aren’t that good at finding knowledgeable people to advise them. I have no understanding of how Leon Black was, but often they just end up relying on people they know, that are really close to them.”

William LaPiana, a professor of Wills, Trusts and Estates at New York Law School, offered a similar description of the ecosystem that has sprung up around the super-rich. The professor patiently explained how it was that Epstein might have spotted a looming tax liability in a special sort of trust that Black was using, a relatively new device employed to avoid tax when passing on assets to a family member.

“New situations crop up; the US Treasury department might take a position no one expected,” he said. “The amount of close reading that goes into these can be overwhelming – it does approach a level of biblical exegesis.”

Witnesses told Dechert that “Epstein would get into the weeds on obscure issues about which otherwise highly competent Family Office employees were not knowledgeable”. He was very good at doing this when it came to negotiating the contracts on private jets, apparently. The Dechert report says that a private jet dealer “was not pleased when Epstein got involved” because he knew the business so well and “it would be hard to negotiate against Epstein”.

LaPiana felt that Epstein had performed a valuable service, although he was still amazed at the sums involved. “What in the world could have caused a $US600 million tax problem?” he said. If the tax rate is 40 per cent, “that’s 40 per cent of a whole lot of money”.

He added that people with tremendous wealth “must be paranoid all the time. Everyone’s going to take advantage of you.” Epstein was apparently adroit at gaining introductions into the presence of such people.

Once he was working for Black he “made repeated efforts to ingratiate himself with other senior executives at Apollo [Black’s hedge fund] and appears to have relied on Black to help him make those introductions”, the Dechert report says.

There was no evidence that any retained him, but it does show something of how he operated. There may even be some billionaires who rather like paying whopping sums for the advice of someone with no official credentials. “The ability to pay enormous sums for advice magnifies your own importance,” LaPiana said. “They say, ‘I think I know this person, I trust this person, look at who this person hangs around with.’ ” He added: “Have you ever met someone of great wealth who didn’t think they were a terrific judge of character?”

The Times