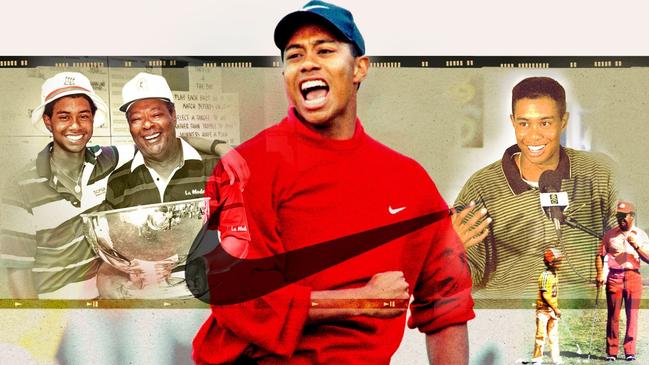

Tiger Woods, Nike and the deal that changed sport forever

From death threats and boycotts to scandals and world domination, the inside story of the 27-year partnership that has made the golfer half a billion dollars richer.

The man who fuelled the death threats and boycotts has led an interesting life. “The kid in the candy store who got paid to be in the candy store,” says Jim Riswold, an advertising creative turned experimental artist who is now living with leukaemia.

He met Bugs Bunny, saw Michael Jordan naked and was fired by his idol David Bowie, who then sent him a Christmas card. The basketball star Charles Barkley called him “a role model for morons”, baseballer Bo Jackson dubbed him his “favourite haemorrhoid” and film director Spike Lee said he was “not bad for a white guy”. And then there was Tiger Woods, flying Big Macs and the $US40 million deal that ripped up golf’s rule book.

Last year’s film Air was the biopic of the sports deal. It documented how Nike courted Jordan and saved the company’s basketball division. It received a mixed reception, but the facts of the golf version outdid the fiction.

We will get back to Riswold, but Woods, now 48, and Nike have both seen better days. The prospect of the 15-times major winner limping through the Masters shorn of his swoosh cap and clothing is a reminder of how a corporate behemoth changed the face of sports sponsorship but is now trying to save $US2 billion ($3bn).

If he makes it to his tee time at Augusta next week, the middle-aged Woods will wear his new Sun Day Red brand, but the boy wonder and Nike were a symbiotic marriage. Rod Tallman, Nike’s marketing chief at the time, tells of how the company’s “sleepy” golf business went from a pre-Woods $US30 million to $US200 million in two years. In turn, over a 27-year partnership, when both player and company would be embroiled in headline-grabbing scandals, Woods would make half a billion dollars from Nike deals.

The severing of the alliance in January was the end of a story that had money flooding into sport and golfers marketed as athletes. Brands are now built from celebrities who take equity stakes in companies. A star like LeBron James can sign a lifetime deal with Nike worth $US30 million a year. It is a world away from the start.

Although Nike had dabbled in golf since 1984, many inside the company felt it should not even be part of the company. “Golf was the red-headed stepchild,” says Tallman, who was appointed director of marketing for golf in 1994. “There was always a debate inside Nike about whether it was a sport or just a game.”

In Air, Jason Bateman plays Nike’s marketing chief, Rob Strasser. The film version presents a quiet, reserved figure, but Hughes Norton, Woods’s first agent at IMG, says the truth was very different. In his book Rainmaker, Norton says Strasser was “a blustery three-hundred pounder nicknamed ‘Rolling Thunder’ who loved describing himself as ‘loud, obnoxious and fat’ ”. Deals were done on crumpled serviettes, but Strasser passed up Norton’s idea to sign Greg Norman among others.

They did get Seve Ballesteros in 1985 and tried to be edgy by producing denim shorts, but golf was a slow burn and it took Woods to change the ethos. After Tallman was called back from working in Europe, they recruited what became known as the global foursome – Nick Price, Peter Jacobsen, Michael Campbell and Alex Cejka – and Tallman felt the company was finally getting some traction at the 1996 PGA trade show.

Phil Knight, the barefoot guru who had co-founded Nike, also made his mind up. Norton says Knight was “a jock sniffer” but his biggest catches, Jordan and Andre Agassi, were past their prime. “Nike had not signed a megastar in years. They needed a win. The timing was perfect.”

Tallman adds: “To Phil Knight’s credit, he’s a savant at identifying talent no matter what the sport. At that point Nike was turning the corner from its reputation for terrible golf products and Tiger had won two US Amateurs. The word was out that he was going to turn pro. Phil Knight said, ‘Sign this kid, no matter what’.”

Strasser had since left to join rivals Adidas and his replacement, Steve Miller, told Norton he was an outsider and not one of the “Kool-Aid drinkers”. Norton, who would be with Woods for two years of explosion, aimed high after Nike executives had flown to San Francisco to woo the Stanford student. He points out that Woods had been given exemptions into 17 professional tournaments by the summer of 1996 and his best finish had been 22nd. “The thing was Nike had no frame of reference,” he says. “That was the beauty of it. They should have laughed me out of the room.”

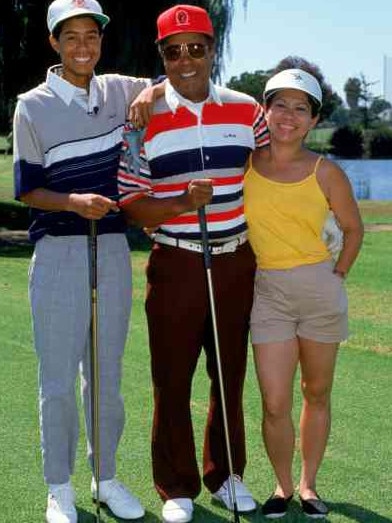

Norton had been monitoring Woods since he was 13, even getting IMG to pay his father, Earl Woods, $US25,000 a year to be a talent scout.

“The guy who ran the tennis division was a friend of mine,” he says. “I looked at the contracts Andre Agassi, Pete Sampras and Jim Courier had and I was blown away by the numbers they were paying guys who frankly were no more top of the heap than the guys I was trying to sell. I thought Nike would be used to those figures even though they were out of this world in golf.”

He asked for a guaranteed $US50 million over five years and a starting point of $US500,000 per major victory, with the same if Woods reached world No 1. He did not mention that the deal he had struck for Curtis Strange a decade earlier had been worth a mere $US5000 per major. Nike offered $US8 million over five years.

Woods duly won his third US Amateur title in 1996. Before leaving Pumpkin Ridge, some 15 miles from Nike’s Oregon HQ, he was taken to a room where Riswold, then with the renowned Wieden+Kennedy ad agency, had a videotape in his hand. He slid it into the video player and showed him a 60-second advertisement. It started with the line: “I shot in the 70s when I was 8,” went on to “Hello world” and concluded with the incendiary: “There are still courses in the US I am not allowed to play because of the colour of my skin”.

Riswold recalls: “We’d bet on him winning his third consecutive US Amateur. There really wasn’t a contingency plan if he didn’t. Got to have faith, I guess. I had gotten to know Tiger while Nike was pitching to him and King Earl. Tiger makes it easy on us and comes from behind and wins.

“We’re all drinking out of the championship trophy – Phil, Earl, Butch Harmon [former coach] et al. Phil makes an introductory speech along the lines of, ‘My friend Jim Riswold here says this is the best ‘spot’ he’s ever done for me. I’ll let you be the judge of that.’

“Honestly, I wasn’t sure how he would react to the ‘colour of my skin’ line. At first, it was silent. I think I might throw up. They don’t like it? I ask myself. Then Tiger breaks the ice and, with a big grin on his face, asks, ‘Can I see it again?’

“We play it over and over and over and drink out of his trophy over and over. At some point, Earl makes a toast and says, ‘Bobby Jones is turning over in his grave.’ ”

Two days later, after taking Knight’s private jet to his professional debut at the Greater Milwaukee Open, Woods signed his mega-deal with Nike and a $US20 million one with Titleist. The next day, in front of a ravenous media, he approached the microphone and muttered: “I guess it’s, ‘Hello world,’ huh.”

It was a sign of just how scripted and forced his public image would become. Nobody had seen the advert at that point, but later that week “Hello world” aired on CBS and ESPN while The Wall Street Journal carried a three-page spread. And that was when all hell broke loose.

“The golf world that had just started to bring us into the fold turned on us,” Tallman says. “We got death threats in our offices. Jim Riswold got them. Tiger certainly did, I know that for a fact, but of course he was used to that.”

There were two strands to the vitriol. The first was the enormous amount of money paid out to a golfer who was a brilliant amateur but rookie professional. Norton now looks at the size of the numbers and says he was an agent of the “wretched excess” pervading modern golf.

The second was the fact that nobody could come up with a club where Woods was barred because of his skin colour. When quizzed, a Nike spokesman said it was not meant to be taken literally, but was a reflection of the general discrimination in the sport.

Golf undoubtedly had an ugly past when it came to race – it had been 1975 before a black player received an invitation to the Masters – but the campaign was seen as manipulating history. It also served up the misconception that Woods wanted to be an outspoken agent of social change. Riswold says Woods was much happier with another advertisement in which he did not speak.

“Tiger preferred the messaging of ‘I am Tiger Woods’. That was more about expanding the game than drawing a sword against it. Me? I still like the fire of ‘Hello world’. ”

But plenty of people didn’t. “All we did was put a mirror up to the golf industry and that made people crazy,” Tallman says. “The combination of that ad and signing him to the biggest contract in golf was too much for the super-conservative old-school golfers. There was a race component to a lot of it.”

Many green-grass golf shops, the traditional pro outlets, boycotted Nike goods. Tallman flew to Atlanta to meet southern sales reps to plot a defence. “I’m sorry I didn’t keep the death-threat letters,” he says. “But it was an ugly period and there was real hatred. They thought this kind of money was ruining golf.”

Success was the balm, and the temperature changed the following year. “When he won the Masters in 1997 by 12 strokes people started to think, ‘Maybe this kid is worth it,’ ” Tallman says.

“That’s when the tide turned. Suddenly everyone at Nike was pro golf, although there was still a lot of animosity in the green-grass shops and especially in the southern part of the USA.”

As Tiger-mania became a phenomenon, both the player and company reaped huge rewards. His next deal in 2001 was upped to $US100 million over five years. That morphed into $US320 million, with his last 10-year extension worth $US200 million.

Yet the Nike Tiger jarred with the real one. “Tiger liked the irreverent approach of Nike and the fact people like Michael Jordan and John McEnroe had transcended their sport,” Tallman says. “We felt Nick Price could be our classic country club golfer and Tiger could be this young, athletic sports golfer. So that’s what we did.

“We had two different lines in both footwear and apparel. The sports brand was much more aggressive and unusual. The first shoe that came out was so different to anything before. It was too OTT and it was never successful, but Tiger liked that at first. Over the long haul, though, it turned out Tiger was actually more of a classic guy.”

Norton was fired by Woods in 1998. Tallman left Nike that same year because of internal changes and feeling drained from fixing problems. “All of a sudden everybody at Nike was a golf expert,” he says.

Riswold remained to write the ads and there were some good times along the way. “My favourite interaction with Tiger was when I beat him in a putting contest, right after he gave me a putting tip,” he says.

“He got mad. Had to pay me with a Big Mac, fries and a large chocolate shake. He threw the bag at me. The man does not like losing.”

Another hugely successful Nike campaign involved Mars Blackmon, a fictional movie character and Jordan fan played by a young director-actor Spike Lee. He became synonymous with Air Jordan shoes, and the runaway success of the ads fuelled Lee’s Oscar-winning career directing acclaimed films such as Malcolm X and BlacKkKlansman.

There was even talk of Mars Blackmon being used to sell golf. “We could have gotten kids to wear spikes to school,” Riswold says. “We even wrote a dictionary, ‘How to Talk Golf’ by Mars Blackmon. It died a horrible, miserable death at Nike.”

An early script also had Woods starring in Space Jam 2, the sequel to the hit film starring Jordan and Bugs Bunny.

Knight’s love of Woods was cemented in 2004 when his son, Matthew, died from a heart attack while scuba diving in a lake in El Salvador. He recalled that as well as about 2500 letters, emails and cards, every single Nike athlete sent condolences.

“But the first was Tiger. His call came in at 7.30am. I will never, ever forget. And I will not stand for a bad word spoken about Tiger in my presence.”

That may partly explain why the company stuck with Woods when his carefully curated public image was ripped apart by a salacious frenzy in 2009. “A minor blip,” was Knight’s assessment of his star’s infidelity and philandering.

Standing by their man was not merely down to loyalty, though. In 2005, when Woods’s ball had famously dithered on the cusp of the cup before dropping in during his final round at the Masters, the Nike swoosh magnified for the prime-time audience, the exposure led to a sales rush on the new ball.

When Woods won the Masters in 2019, it was estimated that Nike’s stock value rose by 5 per cent and boosted Knight’s personal fortune by $US250 million.

Nike had been similarly happy to stick with Lance Armstrong despite years of rumours and investigative journalism about his doping. They finally parted ways in 2012, the year the company “vehemently” denied a claim made under oath that it had paid $US500,000 to Hein Verbruggen, the former president of the UCI, cycling’s world governing body, to cover up a positive drug test.

In 2019 Alberto Salazar, the head of the renowned Nike Oregon Project (NOP), was banned for breaking anti-doping rules. Last November, Nike and Salazar settled a $US20 million lawsuit against an athlete who said she had been emotionally and physically abused while at the NOP. Mary Cain accused Nike of not doing enough to protect her. The company and Salazar denied the claims.

If Nike emerged unscathed from most of this, the split with Woods is symbolic of a shift where it hurts. Its foray into making clubs failed spectacularly and they shut the division in 2016. There are reports that Nike wants out of golf altogether and the Tiger Woods Conference Centre on Nike’s Beaverton campus is now a totem to past glories.

Roger Federer, another company stalwart, quit for a better deal with Japan-based Uniqlo in 2018. It is easy to imagine the disappointment felt by Knight, who retired as chief executive months after his son’s death but remained as chairman, when Woods wore FootJoy shoes to aid the comeback from his 2021 car crash. Deemed a bellwether of global markets, Nike said in February that it was cutting 1600 jobs.

Tallman, now a notary who lives near the Nike campus, says the Woods story shook up a sport. “Golf was a sleepy category, but that time challenged the rest of the industry to up its game,” he says.

And how the money has flown beneath the burning bridges. When the split with Nike was confirmed, Riswold was asked to come back to write one last farewell ad. He came up with: “It was a hell of a round, Tiger.” These days he is usually a subversive artist, dressing Hitler and Putin dolls in absurdist garb, although he says he may have overestimated the Kim Jong-un market. Golf has changed too.

The Times