The ‘screenwriters’ giving Gen Z their subtitles fix

Younger viewers increasingly want legible dialogue. Thousands of freelance workers are required to write it

Subtitles were once mainly used by the hard of hearing and fans of foreign-language films.

Now, however, demand is booming because of Generation Z’s love of them, partly so they can follow the plots of films or television series while simultaneously keeping an eye on their phones. A survey in 2021 by Stagetext, a charity for the deaf, suggested that four out of five viewers aged 18-25 used subtitles all or part of the time.

Add in the surge in non-English-language programming on streaming services, and the result is increased demand for freelance workers around the world to provide the text for what is happening on screen. That includes background noises and descriptions of music and sound effects, as well as any dialogue.

Emmanuel Denizot, a subtitles expert and translator with 25 years’ experience, said his skills had never been more in demand.

While shows such as Netflix’s hit South Korean import Squid Game make subtitles essential for western audiences, studios rarely have in-house teams to produce the accompanying text.

That is where workers such as Denizot, who lives in Paris, step in. He said: “That is our life. We are all film buffs and we watch a lot of TV series. I love it so much and I never get bored. And I never will, because the material has so much variety. I work on films and series from different countries that have all kinds of themes and settings.” While demand has soared, wages have not, according to Denizot, who said pay had largely remained stagnant in the past decade.

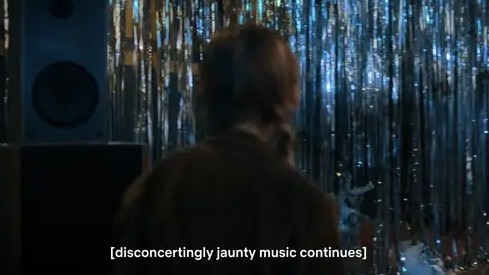

Producing captions is a creative process, he believes, because workers must offer concise interpretations of what is happening on-screen, especially in the case of unusual sound effects.

Most studios have their own style guides, to which workers must strictly adhere. Netflix’s is public and includes the requirement that “dialogue must never be censored”, while there is a set reading speed of up to 20 characters per second for adult shows and up to 17 for children’s programming.

Disney’s is said to contain detailed directions related to its best-known characters, including which words are to be used for R2D2’s beeps in the Star Wars franchise. The company even spells out how the swoosh of a lightsaber should be explained.

Subtitling companies have sprung up to meet the booming demand. One such business, the Austin, Texas-based Rev, employs freelance workers – up to 75,000 around the world – who can turn around a job within 24 hours. It can pay up to dollars 1.10 for each minute of runtime and its workforce includes those with years of experience and newcomers looking to make money on the side. The company allows workers to pick and choose which films and television shows they work on, leaving some who love reality TV to indulge in their favourite genre.

Pat Krouse, Rev’s vice-president of operations, told the Hollywood Reporter: “We have people, for example, who love doing documentaries because they’re like, ‘I feel like I’m learning something and I’m getting paid to do it.”

As in other industries, captioning workers are nervously watching the rapid developments in artificial intelligence and wondering whether they will soon be out of a job.

AI is already used for some subtitles, usually as a rough guide before a human worker takes a second look.

Even the most sophisticated system has its limits. AI struggles with content featuring numerous speakers and it cannot yet describe sound effects.

Denizot admits there is some concern about the rise of AI but is confident the human touch cannot be replaced. He said: “There’s so much creativity involved. Emotions, feelings – that’s what film is about. So there’s very little chance a machine could ever replace this.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout