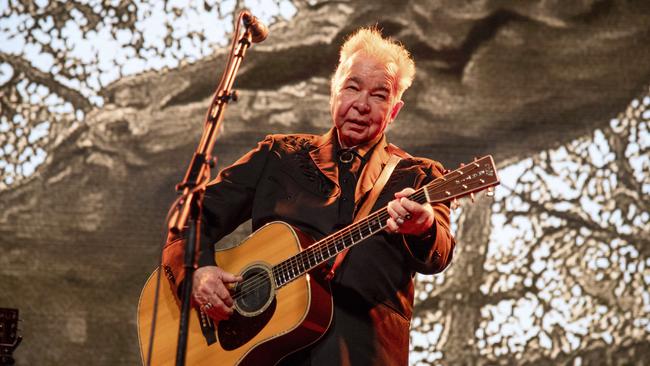

The poignant existentialist: remembering John Prine

John Prine deployed sharp wit, vernacular poetry, satire, sentimentality and realism to express the joy and despair of the human condition.

OBITUARY.

John Prine. Singer-songwriter. Born October 10, 1946. Died from Covid-19 on April 7, aged 73.

When Bob Dylan was asked in 2009 to name his favourite songwriter, he nominated the “pure Proustian existentialism” of John Prine.

In the early 1970s when Dylan had abdicated his role as the “voice of a generation” Prine was one of several up-and-coming singer-songwriters to be burdened with the tag “the new Dylan”.

Others touted at the time included Loudon Wainwright, Steve Goodman, Jesse Winchester and a young chap named Bruce Springsteen, but with the exception of the latter, Prine proved to be the most enduring of the “new Bobs”.

READ MORE: Andrew McMillen’s interview with John Prine

Dylan recognised his talent from the outset, too. Shortly after the release of Prine’s debut album in 1972, Dylan turned up at the Bottom Line club in Greenwich Village to hear him play and got on stage to back him on harmonica for a song about a Vietnam veteran turned junkie called Sam Stone.

The song’s punch line — “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes, and Jesus Christ died for nothing I suppose” — was hailed by Dylan as one of the most evocative in the canon of popular songs as social commentary. “Nobody but Prine could write like that,” he observed.

Prine deployed sharp wit, vernacular poetry, satire, sentimentality and realism to express the joy and despair of the human condition. His artistry lay in expressing universal sentiments that others could recognise but not articulate. With a wry and sardonic view of the world, which Prine characterised as “optimistic pessimism”, he crafted a catalogue to rival any songwriter of his generation.

There were tales of lonely hearts (Donald and Lydia), lost dreams of youth (Angel From Montgomery), and bad habits (In Spite Of Ourselves).

Dylan called the songs “Midwestern mind trips to the nth degree”. Bonnie Raitt considered Prine a singing Mark Twain. The country singer Kacey Musgraves declared: “Anytime a line is not working for me I’ll think: WWJPD.” It stood for What Would John Prine Do.

His wit and ingenuity failed him only once, when he tried to write a song about Donald Trump with the working title Dear Mr President. When he realised that the song had descended into a rant before the first verse was over, he abandoned it. “But I think the real reason was that I secretly kept hoping he’d be gone before I could get into the studio,” he said.

His albums won him a brace of Grammy awards and those who covered his songs included Carly Simon, Johnny Cash, John Denver, Bette Midler and Joan Baez. Yet nobody delivered Prine’s lyrics with quite the same warmth and humanity as he did, singing in a slyly quizzical voice that straddled folk and country. His female singing partners included Emmylou Harris and his third wife Fiona (nee Whelan), whom he married in 1996 after they met while he was touring Ireland, a country he loved and where he kept a second home. He recalled their introduction at a bar in 1988: “Fiona said, ‘I saw you play when I was 17. When will I hear you next?’ And I said, ‘Right now,’ and walked up on stage with her and just started playing. And oh yeah, it was love at first sight.”

She acted as his manager and survives him along with their sons, Tommy and Jack, and stepson Jody Whelan. He was formerly married to his high school sweetheart Anne Carole, and between 1984 and 1988 to Rachel Peer-Prine, who sang harmonies on his records and played bass in his backing band.

Reflecting on becoming a father for the first time aged 48, he said: “It put my feet right on the ground. I didn’t know that I was missing that until I found it. All of a sudden I felt normal with a capital N.” His sons inherited his love of music — Tommy is a guitarist and Jack a songwriter.

The attention that Prine’s songs brought him was not always appreciated. He grew thoroughly fed up with the “homes of the stars” bus tours which stopped outside his Nashville property twice a day to stare at the house of his neighbour, the American Idol singer and TV star Kellie Pickler.

According to his son Tommy, his way of dealing with the intrusion was to bemuse the celebrity spotters by standing by his mailbox dressed in “bright-red sweatpants and gravy-stained T-shirt”. When he tired of that joke he moved to a $2.6 million property away from the bus tours and with more space for his collection of antique cars.

Wilfully eccentric and with an unassuming manner, he once sang: “The world will end most any day, but if it does, that’s OK ‘cause I don’t live here anyway.” Fiona insisted that for once he was being serious. “He’s somewhere else most of the time.”

John Prine was born in the Chicago suburb of Maywood in October 1946, the youngest son of Verna (nee Hamm) and Bill Prine, a factory worker who had moved north in search of work from the Kentucky coal mines. At school he was known as “Tippy Toes” for his prowess at gymnastics but by the age of 14 his prime interest was folk music. Under the influence of his older brother, Dave, who played fiddle in an old-time band, he learnt to play the guitar with an unfussy finger-picking method that served him all his life.

After leaving school to become a postman, at 20 he was drafted into the US army and served in West Germany as an engineer, “drinking beer and pretending to fix trucks”. On his discharge he returned to his old job in Maywood and began composing songs in his head to alleviate the tedium of his round. After a few beers one night in 1970 in a Chicago folk club, he was dared to perform at an open-mic session.

He soon became a regular and his break came when Kris Kristofferson heard him at the club. “It was incredible,” the writer of Help Me Make It Through the Night recalled. “John was singing some of the best songs I’d ever heard, timeless, completely original and unpredictable.”

Kristofferson took him to New York, introduced him to Dylan and invited him on stage during one of his shows. Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records was in the audience and Prine was offered a record deal the following day.

Over the years his albums sold steadily but by the mid-1980s he was a dispirited mess, sleeping until the middle of the afternoon and partying all night. To break the spiral he even contemplated a return to being a postman. Instead, celebrity friends rallied round and after a five-year sabbatical from the recording studio he returned with The Missing Years (1991). It won him a Grammy for best contemporary folk album and re-energised him. Still touring many years later he mused: “If I was still a postal worker, I’d be old enough to retire.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout