The fast diet - should you still try it?

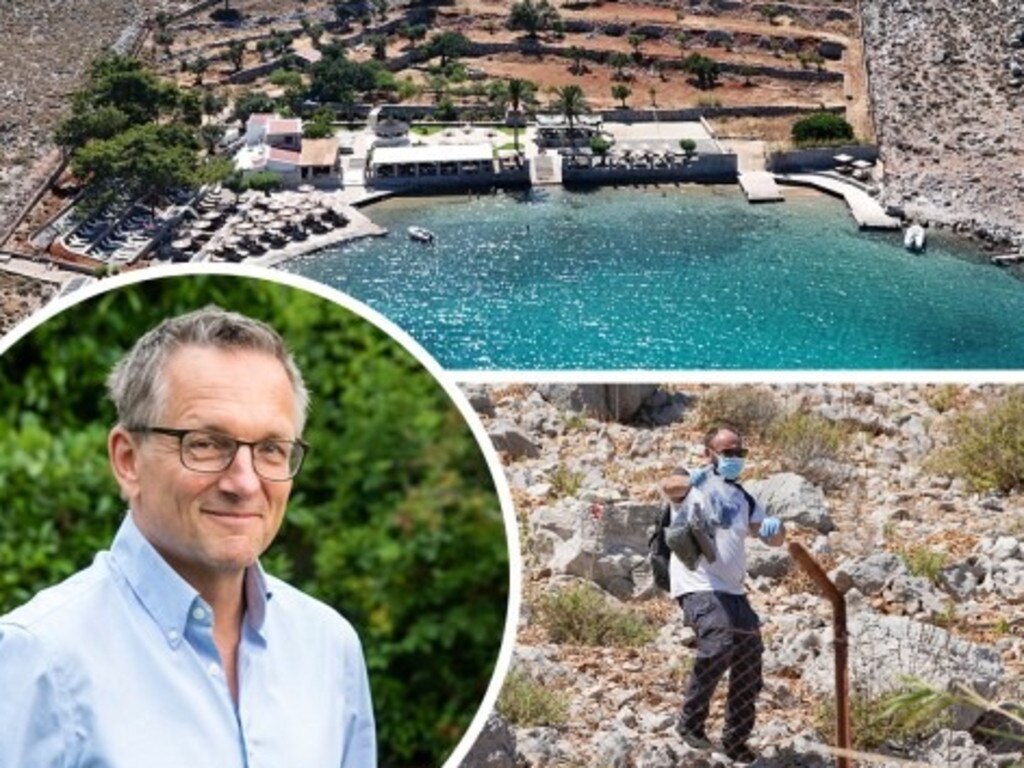

Michael Mosley kick-started the trend for food restriction on limited days with his 5:2 weight-loss plan. But is it backed by science now?

Remember trying to lose weight before Dr Michael Mosley introduced us to intermittent fasting (IF)? Of course you do. Who could forget the torturous calorie counting, cutting carbs or eating so much protein that your breath smelt like a stagnant pond, all of which went out of the window when we realised stripping away body fat could be as simple as eating less on selected days.

Mosley’s original 5:2 diet soared to popularity after a 2012 Horizon documentary in which he investigated the benefits of consuming only about 500 calories (600 for men) on two days a week and what you liked, “with little thought to calorie control and a slice of pie for pudding if that’s what you want”, the rest of the time.

It worked for him, and the rest of us were instantly sold on his research-based discovery that we could get slimmer and healthier with limited days of food restriction. A series of bestselling books, including The Fast Diet, followed with celebrities including Jennifer Aniston, Benedict Cumberbatch, Beyonce, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Jennifer Lopez adopting the diet - or a variation of it - to keep pounds at bay. Dieters have never looked back.

New twists on the IF formula keep coming but the stop-start cycle of eating and avoiding food has a firm and indestructible fanbase. From the 5:2 to the OMAD (one meal a day), the 6:1 diet (in which you fast once a week) to the TRE (time-restricted eating) methods such as 16:8, in which you restrict calorie intake to a set daily “window”, the promise is that there is a fasting approach for everyone. But as scientists conduct ever more rigorous studies on its benefits, does IF stand up to scrutiny? Here’s what we know:

Is intermittent fasting the fastest route to weight loss?

What we love about IF is the routine it provides. Weight loss is often rapid in those who try it, but surprisingly pounds are not shed at a greater rate than by following a traditional weight-loss diet. It just feels easier. Last year a study at the University of Illinois, Chicago, followed 90 obese adults who were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a 16:8 time-restricted fasting group who ate only between noon and 8pm; a calorie-counting group who reduced their daily intake by 25 per cent; or a control group who made no changes to their usual eating habits. Results showed the 16:8 group did lose significant amounts of weight - about 10lb over a year - but it was no more or less than the calorie-counters. Both diet groups consumed an average of 425 calories a day less than the control group.

“A lot of people like and swear by fasting for weight loss and for some it works wonders,” says Dr Duane Mellor, a hospital-based dietician and honorary fellow at Aston University medical school. “But it is no magic bullet and not everyone finds it easy. It’s just one way to eat less, which is the key to losing weight.”

Can you really eat what you like on the days you don’t fast?

This year Rishi Sunak said he likes to practise a weekly 36-hour Sunday evening to Tuesday morning fast because it allows him to indulge his “weakness for sugary things” for the rest of the week. It is a common misconception that you can eat what you like on non-fasting days, says Alex Ruani, researcher in nutrition science at University College London (UCL) and chief science educator at the Health Sciences Academy - whereas you should think of a fast as a pause in healthy eating.

“If you generally eat a lot of sugary, highly processed foods and have poor sleep and activity patterns, then your risk of having raised blood sugar and inflammatory markers is higher,” Ruani says. “These can remain raised even during a short fast, so it really does matter that you focus on a healthy diet with plenty of pulses and wholegrains, vegetables and nuts at other times.”

Mellor says that if you are someone who eats excessively on days when you are not fasting, you should not expect rapid - or indeed any - weight loss. “Fasting won’t result in weight loss for everyone simply because some people feel more hungry after a day with little food,” he says. “The result is that they compensate by overindulging on calories when they are permitted, which means you probably are not eating less overall.”

Are the weight-loss results of the 5:2 diet long-lasting?

The pounds will stay off if you stick with the approach, but therein lies the problem, as many people don’t - or can’t - keep it up.

When a team from Queen Mary University of London compared the effects of the 5:2 diet with standard advice on calorie counting and healthy eating in 300 overweight adults, they found that 74 per cent of people managed to stick to the IF diet for six weeks but struggled after that, with only 31 per cent still following it six months later. Twelve months later only 22 per cent were still following the 5:2 plan and, wrote the researchers, both diets produced “similar modest results”. Adding group support initially helped people to adhere to the 5:2 diet, but that “impact diminished over time”.

Mellor says that, for it to work, any diet has to fit with your lifestyle. “In the long term, the 16:8 or 14:10 are more useful for some people because they find them easier to plan in advance,” he says. “It can be trickier to work around two days of more extreme calorie reduction, but ultimately the IF approach that is most effective is one you can stick to.”

Will IF boost your health even if you don’t need to lose weight?

Proponents claim that long-term IF enhances everything from cognitive function and gut health to sleep and a slowing of the ageing process by helping the body to regenerate healthier cells - a process called autophagy - potentially helping you to live longer.

“To date most studies have been conducted on animals, but some of those involving humans have produced encouraging results,” Mellor says. “There’s some evidence that enforced breaks in periods of eating, such as fasting overnight, generate cellular renewal and also positive changes in gut bacteria that promote health.”

For a study in the journal Cell Reports, researchers from the University of Cambridge analysed blood samples from a group of participants who ate a 500-calorie meal, then fasted for 24 hours before eating a second 500-calorie meal. Professor Clare Bryant, a clinical pharmacologist who specialises in innate immunity and who led the study, found that a 24-hour fast between meals boosted production of a lipid called arachidonic acid that inhibits the damaging inflammation associated with diseases such as obesity, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s. As soon as participants ate a meal again, levels of the protective fatty acid dropped, but, Bryant says, the findings hint “that regular fasting over a long period could help reduce the chronic inflammation we associate with these conditions”.

Others, including Valter Longo, professor of gerontology and biological sciences and director of the Longevity Institute at the University of Southern California, have suggested in research that fasting is linked to genetic pathways that regulate levels of insulin, C-reactive protein, insulin-like growth factor 1, and cholesterol, all markers for disease.

Can IF prevent - or even reverse - type 2 diabetes?

In a healthy person, the pancreas produces enough insulin to allow the body to use sugar or store it away appropriately, but type 2 diabetes occurs when that system breaks down and blood sugar levels are consistently too high. There’s evidence, Ruani says, that diets such as the 16:8 can help people to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, particularly in those who carry excess weight around their middle. The so-called fasting mimicking diet (FMD), designed to mimic the effects of a fast with just five days a month of fasting, was also shown to reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in a study by Longo, who published his findings in Nature Communications journal this year.

For those who already have the condition, hardcore calorie restriction and drastic weight loss can help to reverse it. Mosley’s Fast 800 diet was based on components of the DiRECT (short for Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial) studies, funded by Diabetes UK and carried out by Professor Roy Taylor of Newcastle University. In clinical trials published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Taylor showed that almost half (46 per cent) of people with the condition who followed a soups and shakes diet of 700-800 calories a day for 12 weeks followed by six weeks of guided food reintroduction and behaviour therapy were in remission after one year, and 64 per cent of participants who lost more than 10kg were in remission at two years. Known as the T2DR (type 2 diabetes remission) diet, it is prescribed on the NHS for people who have had type 2 diabetes for less than six years.

Is the 16:8 bad for your heart?

It’s not all good news for intermittent fasters. Scientists reporting at the American Heart Association’s Epidemiology and Prevention Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health Scientific Sessions this year warned their study of more than 20,000 adults showed that those who followed a 16:8 diet had a 91 per cent higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease than people who followed a normal eating schedule and spread food intake over 12-16 hours each day. However, Mellor says the study, which was not peer-reviewed, looked only at how people ate on two days and then linked those results to risk of cardiovascular disease.

“Findings were based on people’s dietary recall, which is prone to inaccuracy and didn’t look at what people ate, why they were restricting calories at certain times or whether they were physically inactive,” he says. “If you are overweight, losing weight is generally good for cardiovascular health and this paper didn’t provide proof that the 16:8 is harmful for the heart.”

An analysis of previous research by scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California had suggested that IF can improve blood pressure, blood glucose and cholesterol levels, all of which reduce the risk of heart disease.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout