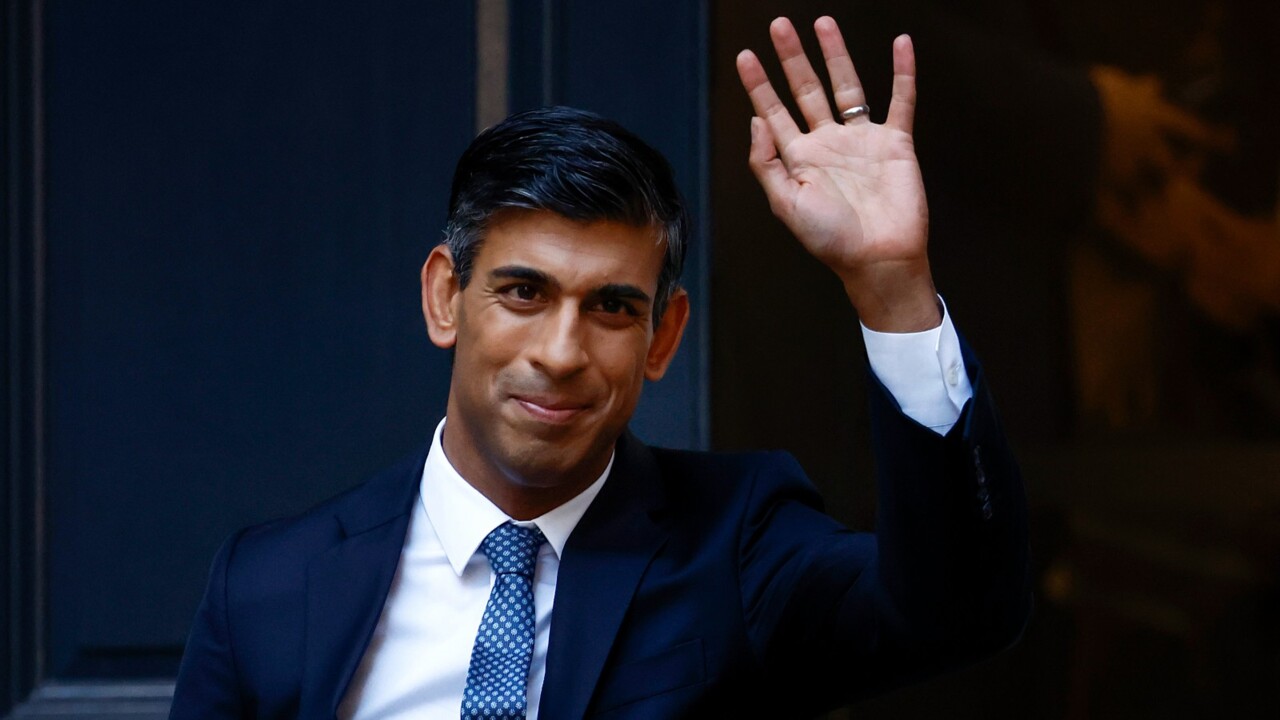

Rishi Sunak’s rise is a quiet triumph for British Indians

The feeling that at last the tables were being turned on the old masters has spread across the Indian diaspora.

Last week a remarkable new entry appeared in Wikipedia. Headed “List of ethnic minority prime ministers of the United Kingdom in the House of Commons”, it consists of just one name: the Conservative MP for Richmond, Yorkshire, Rishi Sunak. It identifies his ethnicity as “British Indian”. Perhaps the elderly lady in sari and shawl who greeted me boisterously in the local Pret A Manger on Tuesday had read it. In any event she was determined not to be ignored.

“Have you congratulated our new prime minister, Trevor?” she called out. Turning to her companions at the corner table, she said: “He’ll have to have Rishi on his programme now.” I smiled weakly. There seemed little point in admitting that 24 hours earlier his team had turned down the invitation to appear on our weekly audience debate programme. “Still waiting for him to drop by, auntie-ji,” I said.

But her emphasis left no doubt that “our” carried a double meaning. Yes, Sunak would be Britain’s third leader this year, but long before he became the whole nation’s property he had been claimed by Indian-heritage Britons. For those who share his ethnic background, the ascendancy of a practising Hindu is their triumph. The odd sourpuss grumbling that a multi-millionaire Tory former public schoolboy should hardly be counted as truly Asian has largely been drowned out by the cheers. But for the rest of us, what does the background of the new occupant of No 10 tell us about what is to come for the UK as a whole?

One thing is already clear. Britons to whom non-Christian festivals seem as marginal as Morris dancing will need to mark some additions to their calendars. This week the Diwali diya tealights were lit at No 10, the colourful rangoli patterns drawn on the pavement.

The feeling that at last the tables were being turned on the old masters has spread across the Indian diaspora. But open triumphalism is not the Hindu way. There are only two countries outside the Indian Ocean where people of Indian origin represent the largest ethnic group: Guyana, and neighbouring Trinidad; 40 and 35 per cent of the population respectively. My own relatives in both countries report a sense of quiet pride about Sunak among communities whose habit is to be modest and reserved.

Elsewhere in the diaspora, there will be more intense feelings, with good reason. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the expulsion of Asians from Idi Amin’s Uganda, after an exodus from Kenya that began in the late 1960s. I imagine in Nairobi, Kampala and Dar es Salaam the feelings of communal achievement are even more pronounced. There, both African persecution and British prejudice are baked into Asian dinner-table conversation. This version of the expulsion from Eden fuels insecurity in a community that still feels it might be rejected wherever it turns. The rise of this generation in Britain at last holds out hope that perhaps there is a place that they might, with confidence, once again call home.

Joy at Sunak’s elevation is no mindless racial attachment. Hinduism is probably the world’s most heterodox major religion, with no prescriptive texts, and hundreds of prophets and deities to choose from. Yet its followers take pride in the boy from Southampton’s embodiment of the virtues they most admire: a stable family life, personal studiousness and self-discipline. They approve of his choice of a steady profession – banking – his first-rate education, and point out to their children that he can read a spreadsheet while pedalling his Peloton.

It won’t matter to them that he’s rich. Most would be puzzled by the focus on his public-school background – head boy at Winchester – or marriage into the Indian plutocracy. On the contrary, writing in The Spectator, the cultural critic Samir Shah points out that among Hindus’ four ruling tenets are artha (wealth) and dharma (duty). Acquisitiveness is admired as long as it’s accompanied by the instinct to share your good fortune with others. Anyone puzzled by Sunak’s entry into the pointless bearpit of politics will see it as a way of balancing the burden of his family’s great wealth.

Of course, not all people of Indian heritage are rejoicing. The subcontinent is a big place with the world’s second largest population and its diversity is legendary. Kolkata’s genteel Bengali intellectuals and Bangalore’s brisk Tamil digital entrepreneurs see their world very differently; and they both have little in common with Mumbai’s hustling Gujarati merchant class. Though Sunak seems an unlikely bedfellow for the extremists who stand behind the nationalist prime minister Narendra Modi, Britain’s million and a half Pakistani and Bangladeshi-heritage Muslims will be wary.

Even the phrase “British Indian” encompasses a multitude. There are at least three separate stories that can be told of this community’s presence in Britain. Until the 19th century most of Britain, if it thought of Indians at all, would have regarded them as shadowy, exotic figures below stairs in wealthy households.

Occasionally a sinister character would cross the pages of a novel. In Wuthering Heights Emily Bronte is obscure about Heathcliff’s origins; the closest we get is that the child is picked up in the streets of Liverpool, probably the offspring of some “Lascar” – Asian – sailor, an impression reinforced by Nelly’s later speculation about his dark complexion: “Who knows but that … your mother was an Indian queen?”

Three non-white MPs sat in parliament before the Great War, one for each of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal parties. All of them hailed from Mumbai’s Parsi community. The longest serving, Sir Mancherjee Bhownaggree, was a distant relative of my first wife’s family; he represented Bethnal Green as a Conservative for ten years from 1895. A supporter of British rule, he was inevitably lampooned as Sir “Bow-and-Agree”.

But it was an Indian cricketer who probably most powerfully shaped the image of Indians in Britain a century ago. Colonel HH Shri Sir Ranjitsinhji Vibhaji II graduated from Cambridge and played cricket for England from 1896 to 1902; the writer Neville Cardus called his batting “the midsummer night’s dream”. A generation of schoolboys, reading the Billy Bunter stories, would have met a fictionalised version of Ranjitsinhji in Hurree Jamset Ram Singh, the Nabob of Bhanipur. On the one hand, Singh spoke the comedy English “as taught by my learned and preposterous native tutors in Bhanipur”; on the other, he showed a tidy pair of fists to a bully who called him “n*****”.

Few would have encountered these exotic creatures in the flesh, but their stereotype dominated the image of British Indians until the post-war arrival of workers from Punjab, Gujarat and Bengal. Many came from the enormous Indian rail network with the skills to expand Britain’s ageing infrastructure. Others filled gaps in manufacturing and textiles. West London saw an influx of workers at the burgeoning airport at Heathrow. The Indian Workers’ Association, born largely at the instigation of transplants from the powerful trade union movement in India, presented a very different prospect to the maharajah class of the previous century.

By the 1970s, Southall in west London, Leicester and much of the northwest had become strongholds for both wings of the labour movement, industrial and political. The industrial confrontation at the Grunwick film processing factory in north London pitted the old against the new in a battle for union recognition. Eighty per cent of the workers were Asian women, led by a Gujarati firebrand, Jayaben Desai, and supported by Labour politicians, including cabinet ministers. The owner, George Ward, himself the son of a New Delhi accountant, was backed by the Conservative opposition and the National Association for Freedom.

As a student activist, I spent several months during the two-year dispute on the picket line myself; the local union leader, Jack Dromey, later a Birmingham MP, used to joke that if I brought the students he’d provide the megaphone. In the end, the strikers were compelled back to work; the moral victory they won in the court of public opinion hardly compensated for the defeat. Desai blamed the unions and the party for a lack of resolve; many of the workers suspected that had they not been Asian, they would have had greater support. It was the start of a flagging of enthusiasm for left-wing politics among Hindu Asians.

There was another factor in the change of sentiment among British Indians: the arrival of a huge cohort of Indian heritage families fleeing persecution in east Africa. This is the start of the real backstory of the third wave of British Indians, of whom Sunak is only the most prominent. The new prime minister’s parents came to England from Kenya and Tanzania; Priti Patel’s family hailed from Uganda; Suella Braverman’s from Kenya and Mauritius.

The historical origins of these families are integral to their political destination. For much of the past two centuries, the British Empire functioned as a great labour market machine, with London deliberately transferring bodies and skills across the globe to fuel the growth of our economy. For example, after the abolition of slavery, tens of thousands of indentured labourers were shipped to the Caribbean to cut cane and grow rice, giving rise to more than half a million descendants, principally in Guyana and Trinidad.

Though I was born in London, I spent most of my childhood living in a village on the edge of Georgetown, Guyana, side-by-side with Hindu Indians. Across the road, the Persaud boys, Albert, Eddie and Ivan, would herd their cows to and fro every morning. The Ganges next door entertained the street with their never-ending rows about money. And several times a week, we struggled through the crowds of women, down from the countryside to sell their fruit and fish, laid out in glistening rows in the local market.

Like many across the empire, the school I attended, though free, was modelled on English public schools. Admission was highly sought after; boys would compete from across the country for places at Queen’s College. It was a given that Indian boys would shine, particularly in the sciences. Even now the top student in the Caribbean equivalent of the A-level exams frequently hails from QC – but these days she is more likely than not to be an Indian heritage girl.

The experience of living away from home in countries where they were no longer in the majority changed these sons and daughters of India. In the subcontinent, some had acted as what Marxists like to call a comprador class – in essence the local agents of the imperial power. In east Africa they put their ability to manage trading relationships to work, becoming successful shopkeepers and merchants.

Yet unlike in the Caribbean, the Indians in Africa were never going to be numerous enough to wield political power, so they also learnt to keep themselves to themselves, largely to stay out of politics and to make their growing wealth inconspicuous. For many decades the strategy worked; but in the long term invisibility became untenable. Accusations of landlordism and wealth hoarding flew as nationalists gained ground. Raw African political muscle – sometimes, as in Uganda, expressed brutally – led to seizure of the assets and expulsion.

The third wave of Indian migrants turned up in Britain with virtually no possessions. But they brought a bucketload of what the social scientists might call social capital. In English this translates into a readiness to (in Sunak’s famous phrase) do whatever it takes to succeed, eschewing short-term rewards for longer-term gains. And they have prospered, not only in politics but in business.

It is now commonplace to observe that the success of several British Indian business empires was founded on a willingness to work in ways that others would not. For example, before the Indians came, supermarkets would close early and never open on Sundays. It was competition from corner shops willing to open all hours that eventually forced the 1994 change in the law, rescuing some of our big chains from extinction.

This is not a specifically British phenomenon. In the US, Indians have flourished mightily. Starbucks has just appointed a new Indian-heritage boss, to join his co-ethnic corporate bosses at Google, Microsoft, Adobe, IBM, FedEx, Barclays and Chanel, among others. There is a political scenario in which the 2024 presidential election sees a contest between Vice-President Kamala Harris and former Trump-era ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, respectively descendants of Tamil and Punjabi immigrants. Most would say that they owe much to their families’ willingness to sacrifice everything else – holidays, bigger homes, new cars – in order to provide a first-rate education in the notoriously expensive American university system.

What may be unique about the British Indians is that paradoxically their prosperity owes much to their African experience. The American author Amy Chua (Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother) in her book The Triple Package argues that successful immigrant groups are imbued with a combination of three traits: a profound belief in their own cultural uniqueness, strong impulse control and crucially an abiding sense of insecurity.

There is little doubt that Indians all over the world share the first two qualities. In building wealth through self-denial and saving, delaying gratification counts. The contrast between the cautious Sunak and the swashbuckling Kwarteng may not in itself be proof of anything; but they tell a story that may one day be backed up by evidence.

But the third element of the triple package – a well-founded sense of insecurity – is probably peculiar to British Hindus. Critics of Sunak, Patel and Braverman carp that they do not understand racism and care little for the vulnerable. Actually, if you have grown up hearing the stories of severed heads in a dictator’s fridge, with the threat that your grandparents’ might join them, you have a pretty good idea of what existential fear feels like. British Indians know what it is like to be menaced and dispossessed, only to find yourself in a hostile land where nobody much wants you. If you’ve survived Idi Amin, being called the “P-word” by a spotty teenager doesn’t seem so threatening. Most crucially, Africa taught the Indians a lesson that turned them into instinctive Thatcherite Tories: that you simply cannot rely on the state to protect and support you if you are in a minority.

In Sunak, Britain has found an almost perfect avatar for the Indian third wave’s long path to security. His leadership will complete the migration of Britain’s million and a half Indians towards the Conservatives. Their votes are distributed widely enough to influence results in marginal constituencies.

Sunak may also surprise us with the stances he takes on some issues. For example, the disproportionate impact of Covid among south Asian households showed that many Indian heritage families, whatever their wealth, preferred to keep their elderly or infirm relatives close to home. I can certainly see our new prime minister appealing to Britons to think more about what families can do for themselves.

More immediately, the absence of concern about his ethnicity in the country at large reveals something completely unexpected. Electorates tend to be comfortable with politicians whose characters they recognise. Nicola Sturgeon is redoubtable and sharp-tongued. People tolerated Boris Johnson because we imagined him to be the type of Englishman who hides his intellect and steel behind a clown’s mask.

I think that in Rishi Sunak we see a completely new archetype – the clever Asian boy who’s decent, earnest and good with numbers. And this model is ours, completely made in Britain.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout