Ralph Fiennes’ Vatican turn is creating Oscars buzz

Ralph Fiennes is tipped for an Oscar for his doubt-stricken cardinal in Conclave. He talks to Jonathan Dean about power, the problem with religion and why he’s never done a TV show.

Many years ago Ralph Fiennes was talking to Hungarian director Istvan Szabo about his face. Or, more to the point, what makes a film leap off the screen and how, in comparison with the stage, it is all about the close-up, each crease in an actor’s skin.

It was the late ’90s and the men were making the epic Jewish drama, Sunshine, with Szabo explaining to his A-lister what he expected from him. Fiennes grins as he remembers this and, since he is a performer, puts on a slight Hungarian accent.

“For me,” Fiennes begins, mimicking Szabo, “the cinema is about the close-up – when thoughts and feelings are born on the face for the first time …”

Then, without a beat, Fiennes switches back to his usual accent – that deep and rolling British tone so delectable it should read satnav. “And you hope the audience leans in since it’s best not to tell the audience what you are thinking.” He pauses, before adding with relish: “What is going on in that face?”

And as Fiennes says this, looking me directly in the eye, I cannot help but think that, of all the actors, no wonder Szabo wanted to work with this one. Is there a more expressive face on film? Fiennes seems to have more muscles round his cheeks than most, moving in unexpected ways, more angles to his eyebrows. This means he can do vulnerable (The English Patient, The Constant Gardener, The End of the Affair); evil (Schindler’s List; Voldemort in Harry Potter); even comedy, from light in Maid in Manhattan with Jennifer Lopez to dark in In Bruges.

Arguably no M in James Bond has carried Fiennes’s depth – not even Judi Dench.

Which leads us to Conclave, a film in which Fiennes has to express a lot with very little movement – his face poking out below the scarlet zucchetto (skullcap) and just above the in choro (choir dress) of his cardinal. (The film previewed in Australia as part of the Italian Film Festival ahead of its general release in the new year.)

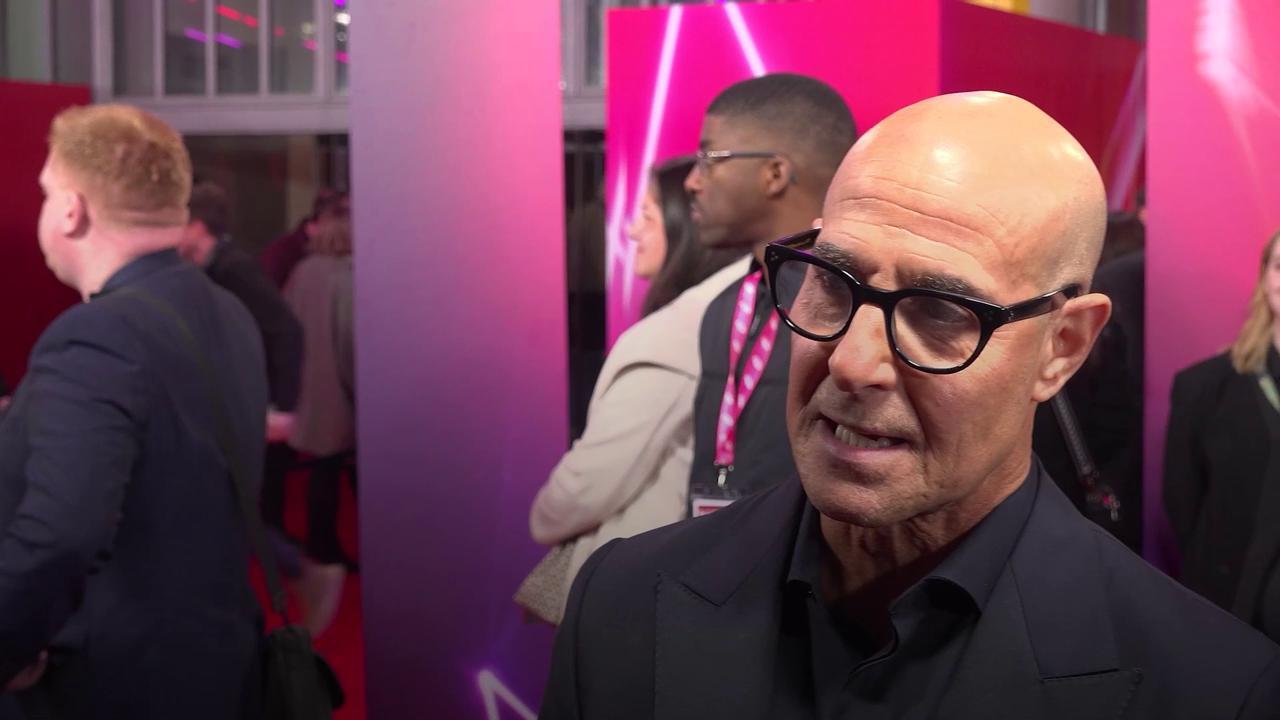

In the blisteringly gripping thriller, based on Robert Harris’s novel, Fiennes plays a Zen-like Cardinal Lawrence, in charge of his peers who have arrived at the Vatican to vote for a new pope. The old one has gone to meet his maker, so Catholicism’s chiefs will pick the liberal Cardinal Bellini (Stanley Tucci) or the traditionalist Cardinal Tedesco (Sergio Castellitto).

Perhaps even Cardinal Adeyemi (Lucian Msamati), who would be great because he would be the first black pope, but not so great because he is homophobic.

Conclave raises such knotty issues – before letting the viewer decide what they think. It’s morally deft, befitting a film directed by German Edward Berger, who made the superb, poignant, intellectually questioning All Quiet on the Western Front two years ago and won seven BAFTAs and four Oscars for his efforts.

We meet for coffee in London – Berger sitting next to Fiennes, the former a booming, engaging man in suit and specs, the latter just as invigorating, perhaps a little harder to read. Conclave is gathering a big Oscar buzz, especially for Fiennes as the inscrutable Lawrence, and, as simple as this may sound, I am just delighted the adaptation of Harris’s page-turner novel is a film – not some 10-part luxurious, extremely stretched, television show.

“I’m so tired of everything being on television,” Berger says. After making his first film at 26, he made a second (Sidewalk Hotel) for “a lot of money” that “just wasn’t good”. He struggled for 10 years after that, doing “super-conservative” TV work “just filling up the air space”, before he realised he needed something to say.

“I just don’t watch much any more. I saw The Sopranos and Six Feet Under, but they even tried to make a show out of All Quiet on the Western Front at first. Someone said, ‘Should we make it six hours of TV?’. But who wants to watch six hours of people killing each other? There is an impulse to turn everything into TV, but Conclave is a two-hour story. We have one character, who goes through a process of an election. Why would we need to expand it into eight hours? It would get terribly boring.”

Fiennes agrees – indeed the actor says he has never been offered a part on a long-form TV show. “Weirdly. That’s interesting. I can’t think of a time I’ve been approached.” He only gets film roles and, like his bold Macbeth last year, theatre work.

“Things are just extended when they don’t have to be,” Fiennes says. “So a show can have great performances, writing, camera, but it’s sort of dead, bubbling along, like somebody’s keeping it on simmer forever for, I sometimes wonder, non-creative elements that might make viewing figures go up. I watched a TV series recently that was well-received and I just thought, ‘Why is it so long?’. It seemed so odd. My natural taste is for film.”

Fiennes was born in 1962 and so grew up with classic films on TV, and came of age in the late ’70s, when cinema was arguably at its peak. He recalls this formative era fondly: he studied at RADA in the early ’80s, first appeared on screen in 1990, in the TV film A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia, and never looked back.

“I just love the classic format of the movie,” he says, beaming. “That is 90 minutes, 120 minutes. People ask what my favourite film is and if there’s one that sums up a succinctness, accessibility and carries a sort of fable, it is High Noon. It’s just the perfect film. Everyone relates to it. It’s a myth. It’s beautifully acted and composed. It’s a personal thing, isn’t it? But I just love that experience of being immersed for a couple of hours – where there’s a total arc.”

Conclave has that sort of arc, a self-contained and intricate story that uses God’s representatives on Earth to show us at our most human, filled with jealousy, betrayal, forever jostling for power. Fiennes, who has played power many times – most notably as the Auschwitz commandant Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List – reels off Shakespeare’s greats of ambition, from Bolingbroke in Richard II to, of course, Macbeth, who is, he says, “a brilliant study of ambition that goes massively toxic”.

Berger knows his film excels at this power tussle, done with few raised voices. One key line is “No sane man would want the papacy!”, and the script suggests that the best person for the big job will be whoever does not want it – which, of course, everyone who did Plato at high school already understands.

“Well, ambition can be healthy,” Berger says. “Because you want to achieve something for yourself or your family and it can help you go to a new place and not stand still. But then you can start feeling it too much – it can cross over and then it becomes an ambition that poisons that person and everyone around him or her. And if a person in leadership wanted it too much? I would be afraid of them.”

Which brings us to religion – this truly is a film of big questions. There is even a terrorist attack. Lawrence is a complex cardinal with spiritual doubt. “I felt empathy with a man struggling to find his path,” Fiennes admits.

What Conclave suggests, though, is that the church is a business now and the spirituality that will draw clergy in has been usurped by the more political traps of pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust and sloth. (Nobody here is really guilty of gluttony.)

“Lawrence’s instincts are to be more monastic,” Fiennes explains. “But he’s found himself in an institution where he’s got to be a bureaucrat and he wants the election to be beautifully done and all smooth. And it isn’t smooth because human frailty, fallibility comes at him from the shadows.”

Berger says this happens in most professions – people start off wanting to be something, a vocation, but anybody successful becomes a manager in the end. “Everyone just yearns to go back to how it started,” he says. “When it was so simple and they did it for the right reason. You yearn for the purity again.”

At which point Fiennes mentions Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I imagine his house has more bookshelves than walls and he rolls into a beautifully told tale, of The Grand Inquisitor part of Karamazov, in which the real Jesus, resurrected, returns during the Spanish Inquisition and says he will set the people free within themselves, only for the Inquisitor to turn him down. The church has power structures that keep everyone in place and pure spiritual light does not fit in any more. “I think that’s the nub of it,” Fiennes says, smiling.

“And the big question,” he continues, on a theological roll, “is whether Jesus was advocating this thing we call the church. He was a guy offering a way on the street, on the mountain. He was saying, ‘Guys! Come round. I’ve got a few ideas to share. Just be true to yourselves, follow the Commandments’. And then Paul goes off, interprets the teachings, and starts this big structure. I don’t think Christ ever said, ‘Go forth and build a big church in big pompous St Peter’s!’. I don’t think that happened. I don’t recall that being an instruction in the New Testament.

“I’m not a practising anything – but I don’t think that I am cynical. Look, I know the history of these churches. They’ve done terrible things. Terrible. But there are human beings in there struggling in their way to find better answers. I find myself thinking that there are people in these structures who are good – not ambitious – who do believe that the church they are in can do good.”

And what about him – is Fiennes still on the path he started on back in the day? Is he the actor he once dreamt of? “Well, you go through all sorts,” he says. “You think, ‘Well, that wasn’t very good. Why did I do that film? What was I thinking?’. Now I just feel lucky if I’m offered a part that taps into a hunger in me. I felt it with Lawrence and, sometimes, you do things for intellectual reasons, or think it will be a good career move. But if you do that, it usually doesn’t end up great because it doesn’t come from that space where you connect with something.”

He smiles and, as I look at him, I know exactly what he means. “And that’s it, really,” he concludes. “It’s important to keep that sense of connection alive."

THE TIMES

Conclave will be in cinemas from January 9