Picasso’s Guernica ready for its close-up

The Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid has lifted its ban on visitors taking photos of Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece.

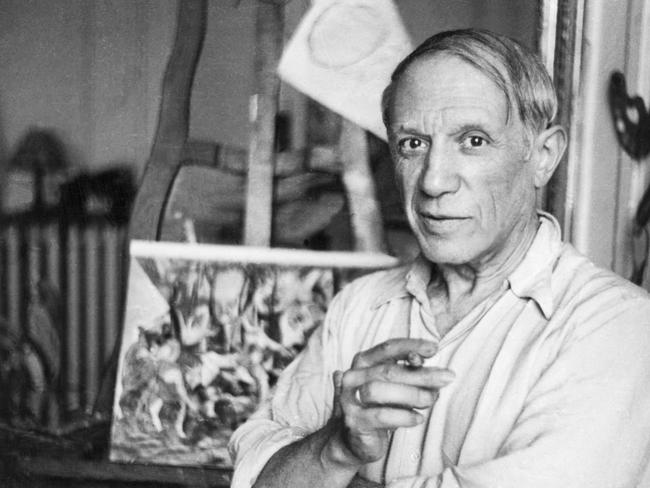

Pablo Picasso was living in occupied Paris when a group of Nazi officers searched his apartment on the Rue des Grands Augustins. They spotted perhaps the first photograph of the vast canvas that would come to memorialise the brutality of fascist rule: Guernica.

“Did you do that?” Picasso was asked. “No, you did,” was his immortal reply.

After hanging for 40 years in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Guernica was finally handed to Spain in 1981, with massive queues forming to see the masterpiece. Yet for decades visitors were forbidden to do what Picasso had done: photograph it.

The ban has now been lifted by the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, which has said photos can be taken of the work as long as a flash is not used. Selfie sticks also are forbidden in front of the painting.

In 2016 an image appeared online of actor Pierce Brosnan posing in front of the artwork, drawing criticism on social media. Controversy was stirred again last year when Mick Jagger struck a similar pose during a private visit to the museum. People complained that it was “only rock’n’roll” to take photographs of it if you were a star.

The change in rules was one of the first decisions taken by Manuel Segade, the museum’s new director, and came into force without fanfare on September 1.

“We believe that it doesn’t make sense for Guernica not to have the iconicity it deserves,” Segade told state-run news agency Efe, adding that people should be able to take selfies with the painting “as happens with any other cultural phenomenon”.

He said: “Our intention was simply that it could be done normally, not to announce it to the press or anything, because photos are already permitted throughout the museum, as in all the great museums in the world.”

The room in which the painting is exhibited is restricted to 70 visitors at a time. Museum officials hope that lifting the ban will decrease the time people spend viewing the painting. “It only takes a few seconds to take a selfie and so the pace of the public will flow more,” said a spokesman. “It does not damage the painting, but rather prevents crowds and people trying to take a covert shot while the guards in the room reprimand them. It will improve the visitor experience.”

At the time of Jagger’s photo the museum justified the ban by saying it prevented crowds clustering around the work. The new rules have produced conflicting reports about whether it has alleviated crowding or made it worse.

Officials at the museum were unsure when the ban was put in place, with one saying it had been in force since the work was moved from the Prado Museum in 1992, and another that it had been put into effect when a protective glass screen was removed in the mid-1990s.

The painting is protected by a sensor that alerts security guards if any visitor comes within two metres of it.

The artwork, inspired by the devastating 1937 air raid by the Nazi German Condor Legion on the Basque town of Guernica at the behest of General Franco, was first shown at the world fair in Paris the same year.

Picasso had been commissioned by the Republican government to produce a work to boost awareness of the war and raise funds.

When World War II broke out he decided the painting should remain in New York for safekeeping. In 1958 he extended the loan until democracy was restored in Spain.

The attack on Guernica, the news of which Franco tried to suppress, was the first aerial bombing to capture global attention. The Basque government estimated 1645 people died among the town’s population of 7000.

The Times