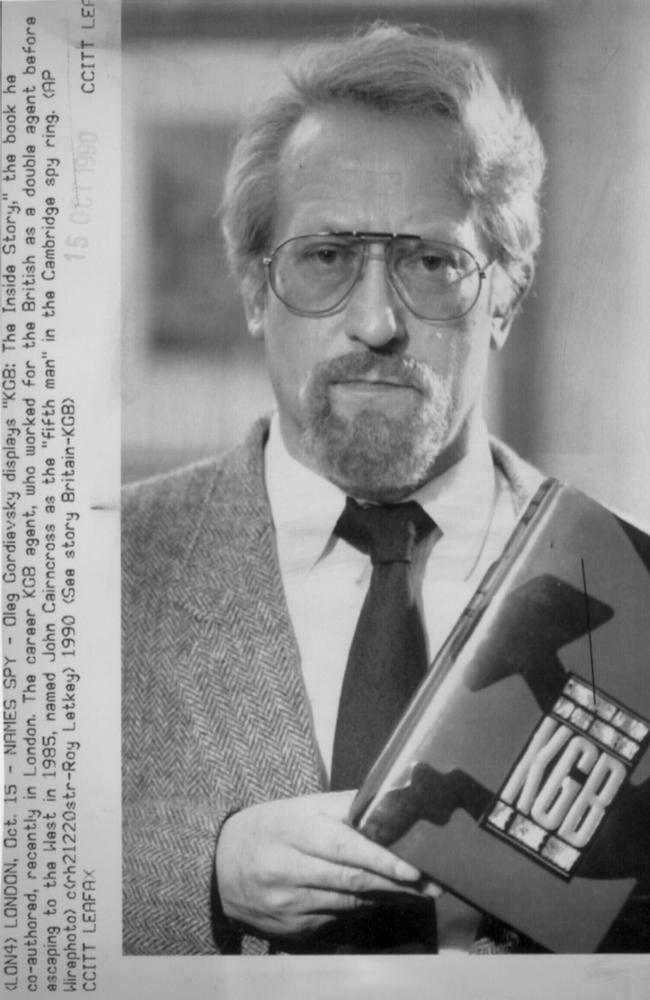

Oleg Gordievsky: the loneliest and bravest man I ever met

The KGB double agent, who died on Friday, was steely, intelligent and could charm anyone — including Angelina Jolie.

One day in 2016, a convoy of three cars pulled up outside the safe-house in suburban Surrey where Oleg Gordievsky, the most important spy Britain has ever recruited, lived for the last 40 years of his life — and where he died on Friday at the age of 86.

I was in the first car. In the second were the MI6 officers who had looked after Gordievsky since the former KGB officer’s escape from Moscow in 1985; in the third, a large black Range Rover with tinted windows, sat Angelina Jolie, the Hollywood actress, and sundry bodyguards.

I was writing a book about Gordievsky at the time. Jolie, a history buff, had discovered this and asked to meet him, with a view to making a film. (The movie never happened, which is why I can tell this story.) It seemed like a good idea. We felt Oleg would enjoy meeting an admiring star.

He had no idea who Jolie was. We sent him videos of her films, which he did not watch. Real history, not drama, was his preferred viewing.

We asked him not to go to any trouble for the visit, but Oleg had nonetheless laid on a vast Russian meal, complete with vodka and pickled herring. Watching Jolie pick her way through that was hilarious.

For the next two hours they sat, locked in close conversation, as he described his life, and she described hers. It was the first time I had seen him “working” a source, charming, funny, inquisitive, drawing her out and pinning her down, the key qualities that go into extracting human intelligence — or “humint”, as it is known in spycraft. By the end they were friends. I could see what had made him such an effective spy.

Born into the KGB (his father was an officer in its predecessor, the NKVD), Gordievsky was recruited by the Russian intelligence service soon after university, rose swiftly through the ranks and was posted to Denmark to run “illegals” — undercover agents. The crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968 was the turning point. Secretly, passionately and permanently, he turned against communism, the KGB and the Soviet state.

Six years later, he was recruited by MI6, after an initial approach on a badminton court in Copenhagen. He spent the next 11 years spying for Britain and managed to have himself deployed to the UK, where he was eventually appointed the KGB station chief, or Rezident.

Gordievsky was able to tell British intelligence (and through MI6, the CIA), not only what the KGB was doing during the most frigid period of the Cold War, but what it was planning to do. His information played a crucial role in averting nuclear confrontation when the Kremlin wrongly interpreted a Nato military exercise, codenamed Able Archer 83, as the prelude to a first strike.

When Mikhail Gorbachev visited Britain in 1984, Gordievsky’s job was to brief the Russian leader on what to say to Margaret Thatcher. Secretly, he was also advising the prime minister: a single spy had the ear of both sides. Unsurprisingly, their meeting was a diplomatic triumph.

Exposed by a KGB mole inside the CIA and summoned back to Moscow, he was forced to activate his escape plan, codenamed Operation Pimlico. His escape signal was to stand, holding a distinctive plastic Safeway bag, on a specific Moscow street corner. In acknowledgment of the signal, an MI6 officer had to walk past him eating a Mars bar.

He was then spirited by car out of the USSR in an escape so improbable and dramatic that no novelist would dare to write it. As they crossed the border into Finland, the MI6 officer played Sibelius’s Finlandia at full volume, a message to the spy curled in the boot that he was free.

A Saab, one of the escape cars used in the Cold War, parked in a field.

One of the escape cars, a Saab driven by the MI6 officer Viscount Roy Ascot

In the four years I spent researching his life, I got to know Gordievsky well, spending more than 100 hours in his overheated living room. His neighbours had no idea that the bearded, diminutive man living next door, under an assumed name, had averted World War Three.

Gordievsky was a complicated character: astute, proud, occasionally irascible. He could be spectacularly rude, but also playful and mischievous. He read widely and deeply, in three languages, and worked with Professor Christopher Andrew on books that are essential reading for any student of 20th-century espionage. His English was excellent, though it started to disappear in later years.

Sometimes we would go to the pub. He loved pubs. He adored England.

But after the attempted poisoning of his fellow defector Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, his security was radically tightened (a death sentence still hung over him) and he seldom left the safe-house.

He became, in some ways, a prisoner of history (I can hear him snorting at the notion). But I never once heard him utter a word of regret for the decisions he had made, though these had cost him his marriage, his wider family, an easy life. After defection, he never saw his mother again.

Why did he do it?

There is an acronym deployed by the intelligence services to denote (somewhat simplistically) the various motivations of the spy: Mice, which stands for money, ideology, coercion and ego.

Gordievsky had no interest in money. Indeed, in the early part of his career as a double agent, he refused all payment. The British state provided him with a home and a stipend, but neither was lavish. Nor was coercion part of his story: he was never forced to do what he did. The decision to return to Moscow, even though there was a danger he had been compromised, was ultimately his alone.

As for ego, Gordievsky was certainly motivated by an acute sense of his historical importance. There was sometimes the whiff of the martyr about him, an embrace of the trials of his life as evidence of his own moral rectitude, proof that he had done the right thing. He enjoyed the fame that followed his arrival in Britain. For a time, he was the toast of western intelligence, touring allied services to describe his extraordinary experience and share his wisdom.

Gordievsky was motivated, overwhelmingly, by ideology. All spies claim to be compelled by a higher calling, but his convictions were real: a free thinker in a society that punished freedom of thought, he became convinced that the communist system was barbaric, illiberal and wrong. He was fighting for the wrong side, and needed to do whatever he could to destroy it. He arrived at this conclusion alone, without external persuasion.

For 11 years he worked for MI6 in the greatest peril, knowing that if he slipped up or was exposed, he would be arrested, tortured and killed.

He often spoke of “duty”. He was a spy in both senses: a trained intelligence officer, but also an agent recruited by a rival service. A professional, his knowledge of spycraft, the dead drops and brush contacts, made him far easier to run: he did not have to be taught how to be a spy.

His belief that, in changing sides, he had done a great service to the world, never wavered. People with absolute convictions can be difficult company: he was sometimes a hard man to like, but impossible not to admire.

The last time I saw him we sat in companionable silence on his sofa and drank red wine as he smoked a stubby pipe that fizzed and crackled evilly. His English had all but gone by this time. The minders who had looked after him with great solicitude for half his life were there too.

I remember asking him if he feared retribution from Putin’s Russia. He curled his lip. Fear was not really part of his personality. This, after all, was a man who had escaped the clutches of the KGB, suffered interrogation and drugging at the hands of people intent on killing him, carried a Safeway bag to a street corner in Moscow and then climbed into the boot of a car on the Finnish border, knowing that if the wrong people opened it, he was dead. I don’t think anything frightened Gordievsky after that.

As we sat there, an urban fox wandered into the back garden. Gordievsky pointed to it, his face lit up and his eyes brightened, and said something in Russian we couldn’t catch. He loved the foxes: small symbols of rebellious liberty roaming the suburban landscape.

The pantheon of world-changing spies is tiny but Gordievsky is in it, somewhere near the top: the most solitary man I have ever met, and the bravest.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout