Jackpot: the inside story of how the US tracked and killed Baghdadi

The families were gathered together when they heard the tell-tale chop of helicopter blades. WARNING: Graphic

WARNING: Graphic

The families were gathered together after dinner, talking and laughing, when they heard the tell-tale chop of helicopter blades. As Abu Mustafa ran outside he saw armed men on the ground aim and shoot at the swarm of helicopters above.

“At that moment the real horror started,” he said, recalling the rockets raining down on the fighters, only metres from the house in which he had taken sanctuary six months earlier, fleeing the Syrian regime’s bombardment.

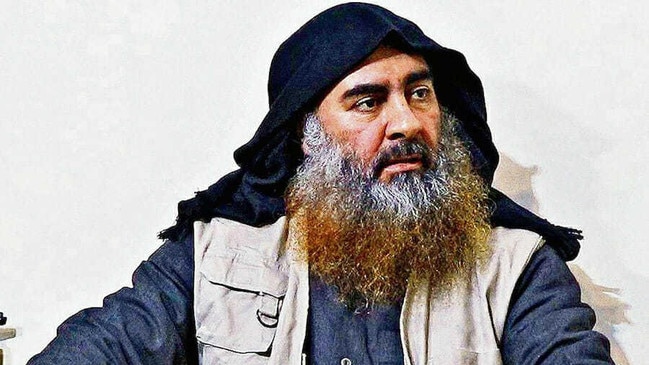

Abu Mustafa had no idea that only three months after his family relocated to Barisha, three miles from the Turkish border, they would become neighbours of the world’s most wanted man, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, 46, the leader of Islamic State.

That night, a week ago today, would mark Baghdadi’s last moments, cornered by an American military dog in an underground tunnel before he detonated a suicide vest, killing himself and two of his children.

Above ground the long-time confidant who betrayed him watched as US Delta Force commandos loaded Baghdadi’s body parts on to a helicopter.

BAGHDADI’S MOVEMENTS

The self-declared caliph of ISIS had long been believed to be hiding in safe houses along the Iraq-Syria border, mostly in Iraq, where he was born. In January he travelled to Isis’s last stronghold in the Syria border town of Baghouz but left before the final battle in which it fell in March, heralding the end of the territorial caliphate.

Much of what was known about Baghdadi’s movements then came from Isis captives. One of the most prominent was Umm Sayyaf, the widow of a senior Baghdadi aide who was captured by the Americans in Syria in 2015.

She was sentenced to death by a Kurdish court in Iraq for her involvement in the enslavement and rape of young women and girls, including the American hostage Kayla Mueller. Baghdadi, among others, raped Ms Mueller, who was killed in Isis custody in 2015.

Sayyaf revealed invaluable information about Baghdadi’s family and inner circle and how he moved around. Her knowledge of his precise movements, however, quickly dated.

Sayyaf told interrogators that the Isis leader always felt safer on the Iraqi side of the border and would not seek a long-term hiding place inside Syria. That began to change as Iraqi forces drove Isis further and further towards the Syrian border. As early as summer last year Isis was preparing to move senior members west from the Iraq border, deeper into Syria, as it came under pressure from the advance of the American-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Receipts recovered from Isis buildings in the eastern Syrian province of Deir Ezzor showed payments to an al-Qaeda affiliate, Hurras al-Din, to prepare safe houses for Isis fighters in Idlib province.

THE INFORMANT

Baghdadi trusted arrangements for his movements to only a small inner circle, which shrank as his paranoia grew. Among them was Abu Hassan al-Muhajir, ISIS’s spokesman, and a close aide and security official whose name remains unknown. That official was to prove the key that unlocked Baghdadi’s case.

READ MORE: ISIS appoints sucessor | Hero dog gets White House homecoming | ISIS on road to revenge after leader’s death

Despite the aide’s seniority, his relatives had been harshly treated by Isis, undermining his faith in the caliphate. “He no longer believed in the future of ISIS,” General Mazloum Abdi, the commander of the SDF, told NBC news. “He wanted to take revenge on ISIS and Baghdadi himself.”

Early this year the official made contact via intermediaries with the SDF, and in April volunteered extraordinary news. Baghdadi had moved to Idlib, a province largely under the control of ISIS’s rival, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which had hunted down and killed more than 100 ISIS operatives in their territory.

The official, a Kurdish informant of Sunni Arab descent, was charged with securing safe houses for Baghdadi, liaising with Hurras al-Din. Because Baghdadi did not use electronic communications, the informant had to meet him in person to discuss security arrangements and moves. Bodyguards sent to fetch the official would take him by car to where Baghdadi was staying.

Because the informant was trusted he was not required to wear a blindfold. He was asked to lie down in the back of the car to evade detection but was able to glimpse the topography and get a sense of his bearings.

In July Baghdadi made his final move, to the compound outside Barisha. The compound, built last year, was home to Abu Mohammed al-Halabi, a senior Hurras al-Din leader. Local residents knew little of the man who claimed to work as a merchant. “Nobody managed to get to know him closely,” said Abu Mustafa, who moved into a house 300 metres away with his brother and their families six months ago.

The distinctively bearded Baghdadi is believed to have never left the compound after his arrival.

The official, meanwhile, visited several times, memorising the architecture of the house, including a tunnel whose entrance was hidden inside.

It took months for his SDF handlers to convince their American allies that he was the real deal. They were won over after he smuggled out a piece of underwear that was DNA matched with samples taken when Baghdadi had been a US prisoner in Iraq’s Camp Bucca in 2004.

OPERATION KAYLA MUELLER

An assault force of 30 Delta Force commandos and 60 Rangers began training for a raid on a replica of the Barisha compound built on the US airbase outside Arbil in Kurdish northern Iraq.

The informant reported that Baghdadi was about to move to a safe house in Jarabulus, to the east. American military commanders visited the White House to ask President Trump to sign off a Saturday night raid named in honour of Kayla Mueller.

At midnight eight Black Hawk and Chinook helicopters, supported by Apache attack helicopters, took off from Arbil and al-Asad airbase in Iraq for a staging post in Syria. Six armed Reaper drones and fighter aircraft took off from Kuwait and five naval guided missile cruisers and destroyers were placed on standby in the Gulf.

The Russian and Turkish militaries, which controlled the airspace over western Syria, were warned to hold fire. The helicopters flew for 70 minutes over enemy territory before arriving above Barisha.

The clatter of the helicopter blades brought local fighters running, believing a regime attack was under way. They fired at the aircraft; the Americans shot back, killing them all.

After landing, the Rangers fanned out to encircle the compound, pushing civilians back as Delta Force commandos rushed the wall with explosives, blasting a hole. An Arabic translator called for non-combatants to surrender and 11 children and two men ran out.

The commandos were confronted by five fighters running towards them, wearing suicide vests. All five were shot dead. Four were women, believed to be Baghdadi’s wives and relatives.

Conan, a Belgian Malinois dog with four years of combat experience, followed Baghdadi’s scent to the tunnel entrance. He entered the hole and was confronting Baghdadi when the Isis leader detonated his suicide vest.

The commandos discovered that Baghdadi had dragged two of his children, both under the age of 12, into the tunnel with him. In the explosion, his head came off whole. A commando looked at it and radioed back: “This is Baghdadi. Jackpot.” A field DNA test proved a match.

The assault forces were on the ground for two hours, collecting Baghdadi’s body parts and laptops, USBs and phones, a potentially valuable cache of information. Before they took off, they turned the other children over to a local shepherd, asking him to take them far away. They loaded the helicopters with their booty, two prisoners, believed to be Abu Mohammed and his son, and the informant. After they took off missiles were fired, flattening the compound.

Baghdadi’s body parts were flown to a naval vessel in the Gulf, believed to be the USS Lewis B Puller, for burial at sea, just as Osama bin Laden’s remains had been disposed of, and the US forces returned to their bases in Iraq.

Morning lit up the scene of destruction on Abu Mustafa’s doorstep. “That night, I felt one of the strangest emotions I have ever felt in my life, a mixture of shock, terror and confusion,” he said. “I thought, did I really live in a house only 300 metres away from the most dangerous terrorist in the world? It’s both terrifying and laughable at the same time.”

By Catherine Philp, Michael Evans and Hannah Lucinda Smith

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout