Inside Zelensky’s Ukraine war bunker: No phones, no light, no sleep

All is darkness in the Bankova, to avoid snipers and airstrikes. There are chandeliers from happier times. You don’t see the sun or know the time.

The most striking thing upon entering the Bankova - Ukraine’s equivalent of Downing Street - is how dark it is inside. Every curtain is closed to protect against bomb blasts and the lights are off to reduce the threat of the building being targeted by air attacks or snipers.

On the day I arrived, Kyiv was enduring its most intense bombardment since the early days of the war. The attack appeared to be the Kremlin’s response to a whistlestop tour of the UK and Europe by President Zelensky, which had secured fresh pledges of weapons, equipment and sanctions on Russia.

I had assumed the darkness was a temporary measure because of the latest onslaught, but I am told it is a permanent feature. As I was shown along the vast corridors and up the grand staircase by a guard, I could not even see my feet and was only able to find my way thanks to the torchlight on his phone.

The Bankova, a concrete block of offices, is surrounded by a ring of steel. Checkpoints line every street surrounding the compound, with access granted only to those who have the correct documentation and passport. Civilian cars cannot get close, and soldiers ask pedestrians for passwords that change daily - often nonsense phrases that Russians would find hard to pronounce.

Earlier that day I had been picked up by security officials at one of the checkpoints and driven in a van through more barriers before entering a courtyard through a huge set of metal gates. Beyond this is the government district, known as the Triangle. Inside, the windows and doors were obscured with sandbags.

Since the start of the war, there have been numerous assassination attempts on Zelensky’s life. Last March, Oleksiy Danilov, the head of Ukraine’s National Security Council, revealed that Zelensky had survived three attempts in one week.

Sitting in a waiting room, still with only the light from a phone to illuminate the eerie gloom, I watched as military advisers wearing khaki uniforms bustled in and out of presidential offices.

Barely anyone flinched as the air raids sounded for the fourth time that day - and no one made a move towards the underground shelter. According to a senior official, the bunker has been used once in recent months, after intelligence was received over the summer that the Russians planned a strike on government headquarters.

A military strategist, holding a large map folded under his arm, emerged from one of the palatial offices where the military cabinet had taken place. He sped off down a corridor marked with firing points to help Ukrainian forces protect the president in the event of a siege.

Shortly afterwards, a soldier sitting nearby sprang to his feet. Others in the room also stood to attention as Zelensky, clearly identifiable by his small stature and trademark black hoodie bearing the words “I’m Ukrainian”, strode through the room followed by a group of advisers.

Andriy Yermak, the president’s close friend and most senior adviser, was among them. He and Zelensky had just arrived back from their shuttle diplomacy mission to Europe, modelled on Winston Churchill’s lobbying of America during the Second World War. Yermak was tired, admitting it had been a “long three days” on the road. The past year has been an endurance test for Zelensky and his officials, who work 18 hours a day, seven days a week, and often sleep in their dark office building for their own protection. They barely see their families.

Zelensky, who has a grown-up daughter, Oleksandra, sees his ten-year-old son Kyrylo about once every ten days. An aide told me that living in the dark away from his wife Olena and children heaped “great pressure” on him.

I had come to Ukraine after interviewing the president last September. That discussion had taken place over Zoom, but having covered Westminster for almost two decades, I was keen to go to Kyiv to discover how a government can continue functioning under the extreme pressure of war. Over the course of a week, I spoke to Zelensky’s closest advisers about the extraordinary challenges faced by the administration in the 12 months since Russia invaded.

Yermak, a former lawyer, is head of the president’s office. Though he rarely gives interviews, he agreed to meet me in one of the Bankova’s oppressive gold leaf and chandelier-festooned reception rooms.

I felt like a mole emerging into sunlight as I was led from the dark of the waiting room into the bright lights of the opulent meeting room, which was briefly illuminated to allow the interview to take place.

How was he coping with the prospect of Putin’s spring offensive?

“We know that they are preparing this offensive and we know that it is . . . a difficult situation,” he told me. However, he was keen to stress that the bombings that day - Russia’s 14th mass missile strike to target critical infrastructure - would have no effect on Ukraine’s resistance. “It’s not changed our positions.”

The immediate crisis during my visit was the brutal battle for control of Bakhmut, a small city in eastern Ukraine once home to a thriving salt mining industry and more than 70,000 people. Today, 6,000 residents remain, surviving mostly underground without power, water or heating. The months-long battle for Bakhmut has cost hundreds of Ukrainian and Russian casualties per day.

Yermak says Ukraine will never give it up. “We have it and we defend it. We are not planning to leave.”

This week will mark the anniversary of Russia’s invasion. For months, many in Ukraine - including Zelensky - had played down the possibility of invasion, despite persistent warnings from American and British intelligence.

Alexander Rodnyansky, a former academic at Cambridge university who returned home to advise Zelensky on economic policy, woke at 4am to the sound of missile strikes on Kyiv. He was immediately invited to join Zelensky and other aides in the underground bunker beneath the Bankova.

Mykola Solskyi, the minister of agrarian policy and food, told me that the night before the invasion he had sent his family to the relative safety of western Ukraine before returning home to “switch off my telephone, because I really wanted to sleep”.

By the time Solskyi woke up and turned on his phone, Zelensky had announced martial law. The leading figures in the Ukrainian government were moved immediately to underground bunkers with orders from the military to stay there until further notice. A Bankova insider said it was a tough existence: “You don’t see the sun, you don’t know the time.” He added: “If Putin was in his bunker [during the pandemic], then it’s not surprising he went crazy. I didn’t want to stay there for long.”

The initial plan was to stay underground for a week. But events outside caused a change of plan. As Russian forces captured towns and cities around Kyiv, it seemed for several weeks that the capital would fall.

Zelensky and his most senior aides, spent the best part of two months living underground, surfacing intermittently to reassure the people that he had not fled.

Those invited to live alongside the president in the underground bunker had to sign a non-disclosure agreement forbidding them from sharing any details about the bunker’s design, location or amenities. They were not even allowed to talk about the food they ate. Isolated below, the team experienced the war through their iPhones. The president’s days were often a succession of meetings, interviews and calls to world leaders. Sleep was snatched and often disturbed.

Hours after the invasion, guards inside the compound turned off the lights as gunfights broke out around the government quarter, and gave bullet-proof vests and assault rifles to Zelensky and a dozen of his aides.

The team inside had to innovate. A key moment was when Zelensky, Yermak and other senior advisers briefly emerged from their underground bunker on the second night of the invasion while Ukrainian forces were fighting the Russians in nearby streets, to record a 40-second speech to his people.

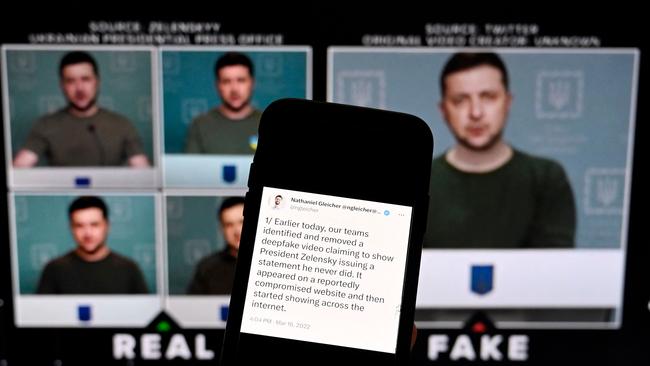

The late-night video clip recorded on the president’s phone was a response to Russian disinformation that he had left the country. “We are all here,” Zelensky said. “We are in Kyiv. We defend Ukraine.”

The speech galvanised the nation.

“It was very important,” said Solskiy, in an interview conducted in the ministry of agrarian policy, an austere Soviet block located close to the Maidan Nezalezhnosti metro station, where Zelensky held one of his first impromptu press conferences after the start of the war.

Zelensky’s determination surprised many. But not Solskiy. “I saw many times that he is very resilient,” he said. “Even stubborn.”

To the amazement of the watching world, Ukraine not only resisted the Russian onslaught but began to fight back. “Firstly, [Russia] underestimated our defensive capabilities,” said Rodnyansky, the former Cambridge academic. “Secondly they over-estimated their own abilities.”

Solskiy was blunter. “What we understand about Russians, is not to expect any clever plans,” he told me. “They behaved in an obvious way.”

As Russian troops fled back to defensive positions in eastern Ukraine and the city of Kyiv gradually began to reopen, those inside the Bankova grew weary of life in the bunker. One official told me of the night he decided to take his chances and leave the bomb shelter to enjoy a meal at a recently re-opened restaurant.

In a moment of mischief, he took a photo of his meal and sent it to a senior Ukrainian MP who had yet to emerge. The source recalls: “He answered ‘Where are you’ and then a lot of swearing. Then he came to the restaurant, ordered a burger and got takeaway for everyone else and took it back to the bunker.”

Though the Russians had retreated east, the Bankova was still in crisis mode. “There has been no period of time where we didn’t have a complicated situation on the battlefield,” said Dasha Zarivna, one of Zelensky’s senior aides.

Rodnyansky said he remained amazed at the functionality of the government, which includes a Monday morning meeting - just as in Downing Street - and a media grid. This is despite the fact that cabinet meetings were for many months being held underground in the Maidan Nezalezhnosti metro station - which also had a surprise visit from the pop group U2, who performed a concert there in May last year.

Rodnyansky said: “A government at war is, in many respects, still very much a normal government. But [because] it’s martial law, there are all sorts of constraints. The atmosphere is different. The priorities and the values - mentally - it’s all about survival now. You don’t have the luxury of thinking about things that you used to.”

To the outside world, Kyiv today looks and feels like any bustling capital. The city’s inhabitants go to work, take exercise, visit the cinema and socialise in bars and restaurants. At rush hour, cars sit bumper to bumper on the main roads as people return home from work.

Yet Kyiv and the rest of Ukraine are still enduring power blackouts after the near-constant bombardment of the country’s critical infrastructure by the Russians.

Residents, who are still subject to an 11pm curfew in the capital, are told to reduce their daily usage but are often plunged into darkness without warning when the energy grid gets overwhelmed.

The hum of generators, which help keep the lights on for restaurants, shops and other businesses, can be heard along many of the city’s main commercial streets. Even the nightclubs have found a way to stay open.

Kyiv and its people have adapted to life at war although the city still bears many of the scars from the conflict.

Destroyed buildings in some neighbourhoods dominate the skyline despite an impressive reconstruction programme. Although people are able to go about their normal lives, despite regularly having to take cover during the frequent air raids, the city’s playgrounds are virtually empty. Kyiv is a city with few children, with many having fled with their mothers to safer parts of the world.

I am told by many of those that I met during my visit that the most difficult thing about life at war is the inability to plan for the future.

Bankova officials are rightly proud of what they have achieved in the space of a year. Few world leaders thought Ukraine could survive the Russian invasion. While Yermak is forced to work in the relative darkness of the Bankova, he hopes recent diplomatic efforts have triggered a lightbulb moment for the rest of the world.

On the eve of the first anniversary of this war, Yermak gave a stark message to Ukraine’s western allies: “It’s possible to end this war in this year. It’s absolutely not necessary to have a second anniversary. Give us everything which we need to win.”

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout