How we fell in and out of love with the BlackBerry

The real tragedy of BlackBerry is not in the reality of what happened but in the fantasy of what could’ve been.

The dizzying new tech-industry movie BlackBerry opens with archive footage of Arthur C Clarke in 1964 being interviewed for the BBC’s Horizon series. In the future, Clarke predicts with barely concealed excitement, the role of the city will cease to make any sense. Thanks to new advances in transistors and satellite technology, physical proximity to other workers will eventually become pointless. And professionals with technological devices, he continues, “will no longer commute. They will communicate!”

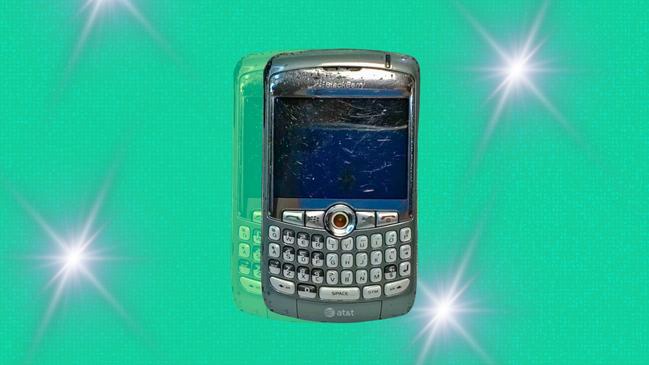

The clip, although delivered with enthusiasm, is double-edged in context. The film that follows is a helter-skelter crash course through the modern communications revolution, and specifically the brief flourishing of BlackBerry, a brand that at its 2011 peak had 85 million global users of its smartphone, deemed so addictive it was renamed the “crackberry”. Developed and maintained in Waterloo, Ontario, the BlackBerry journey ultimately ended, as does BlackBerry the movie, with the arrival of the iPhone and the sense of a world transitioning to the entirely digital, essentially virtual, culture predicted by Clarke’s total communication.

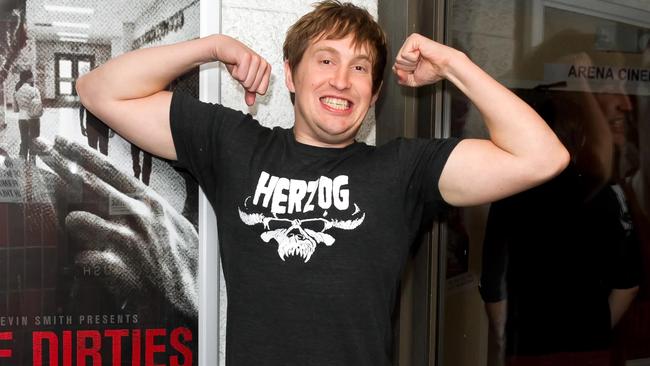

“At a certain level my film is about this last gasp of an analogue product that people liked to touch and feel,” says BlackBerry’s director, co-writer and star Matt Johnson. The 37-year-old Canadian, on a Zoom call from his apartment in downtown Toronto, waxes lyrical about the BlackBerry’s clunky-clicky buttons and robust physicality, and sees a clear through-line between his movie and the recent wave of true-life dramas that appear to celebrate consumer triumphs, such as Air (Nike trainers), Tetris (the Game Boy hit) and The Beanie Bubble (stuffed toys). Johnson has grandly named this phenomenon “vinyl-philia”, and says that it represents a nostalgia for a time when consumer culture mostly made “things” instead of apps, downloads and endless updates. “I think now we’re seeing a desire to go back to a tactile world,” he says. “People want to feel things as opposed to imagining feeling them.”

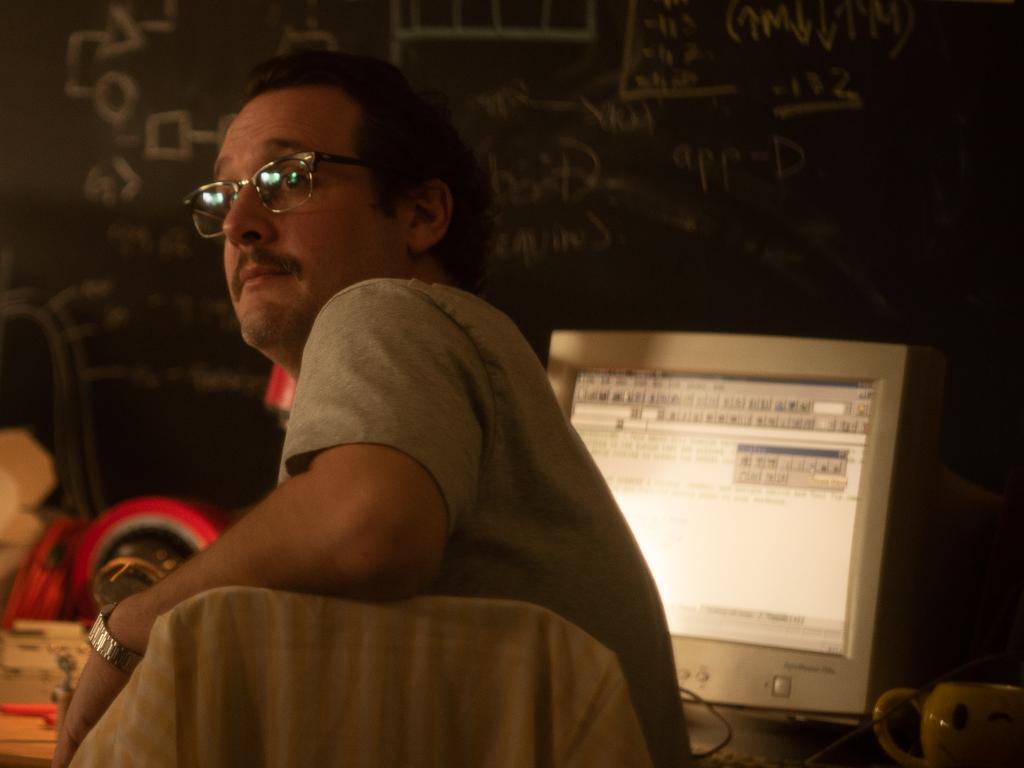

Indeed, the beauty of Johnson’s critically adored movie, and of the consistently eccentric characters who populate it (Johnson’s script is adapted from the nonfiction bestseller Losing the Signal: The Untold Story Behind the Extraordinary Rise and Spectacular Fall of BlackBerry), is a glaring lack of Apple-style hyperbole or proselytising guff about the limitless digital horizon. Instead, Johnson plays the headband-wearing Doug Fregin, co-founder of the BlackBerry developer Research in Motion, a company that tackles the smartphone conundrum with easygoing Canadian naivety. Fregin’s staff, for instance, concentrate only on the task at hand – essentially getting email on a phone – until it’s too late and they’ve been overtaken by their stylish “bigger picture” competitors south of the border.

“These engineers could only see 6ft in front of their faces,” Johnson says. “It was their strength and their curse. And it’s the difference between them and Apple. They were solving the problem in front of them, not providing a vision for a new culture.”

There is something specifically Canadian, he says, about the failure of the BlackBerry. “I think our national habit of reducing ourselves and not trying to stand out winds up inhibiting our ability to reach our true potential,” he says. “Our cultural mandate is not to make too big a deal of ourselves, and that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, whether it’s in engineering, medical sciences or in this case business. Whereas the Americans really have cornered the market on bloviating. But the good news for them is that some of them do wind up as the best in the world.”

Johnson, the son of a GP mother and a father who worked in pensions and benefits, fell into filmmaking through shooting short movies, video pranks and a low-budget web series about talentless musicians called Nirvanna the Band the Show (later revamped and relaunched on Channel 4). His debut movie was a “found footage” drama about school shootings called The Dirties, and he followed it, in 2016, with a drama about faking the moon landings called Operation Avalanche. I tell him it’s nice to see that he has finally made a movie that’s not about making movies. Au contraire, he says. BlackBerry the movie is really an analogy for how film production works. “It’s me, at a deeper level, walking the audience through the filmmaking process,” he says. “You’re watching a group of people coming together to try and do something impossible. It’s a movie about what it’s like to be a young filmmaker, but it’s also totally invisible because it’s actually about a smartphone.”

Johnson, who lectures in film at York University in Toronto, adds that his fundamental mission with every movie he makes is to show aspiring young filmmakers and film students that they can do it too. His bugbear, he says, is Hollywood myth-making. “I hate the idea of the unknowable genius filmmaker,” he says. “Kubrick, Spielberg and Fincher. People who you look at and think, ‘Well, I could never be like them.’ Christopher Nolan is a perfect example of this. He’s someone who’s so articulate, and seems as though he’s living on another level. The general public view him and they’re, like, ‘Oh my God, this person’s a genius!’ Whereas if you’re a filmmaker and you see somebody like that and you watch his films you’re, like, ‘This person is so stupid! I cannot believe he’s getting away with this! He’s essentially a con artist!’ And so by presenting myself as almost a juvenile moron, I think it gives young people the impression: ‘Yeah. I could do that!’

Johnson, perhaps unsurprisingly, has no plans to move to Tinseltown any day soon. He’s putting the finishing touches to a feature version of Nirvanna the Band the Show and is simultaneously working on four new scripts. Yet with BlackBerry’s near universal acclaim and timely cultural commentary, is he not tempted to segue, Greta Gerwig style, into the wider, more ambitious world of Hollywood movie making? No, he answers, horrified. “I have an unquenchable bloodthirsty patriotism that I cannot quite shake,” he says. “Unless something goes terribly wrong I’ll be in Toronto until I die.”

The real tragedy of BlackBerry is not in the reality of what happened but in the fantasy of what could’ve been, he says, almost as an afterthought. At that crucial moment when the iPhone appeared, BlackBerry had a chance to survive and thrive, he says, but it was missed. “Had they exhibited a very Canadian humility in that moment and said, ‘You know what, we see what Apple is doing here with apps and music and maps. So why don’t we go under them and only do text, email and cell?’ I actually think they would’ve found lasting success.

“Because what I see and hear more and more, especially these days, is a consumer culture that is longing for a product that does less. We’re longing for a device that is not flashy and that does not draw so much of our attention. And that’s what these guys originally set out to do. Just do a few things. But do them really well."- BlackBerry is in cinemas from Friday

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout