Gucci offers a gaudy warning about future of high fashion

Instead of opting for Gucci’s garish products, consumers have favoured brands such as Prada and Hermes for their more understated offerings. Then there are those fakes.

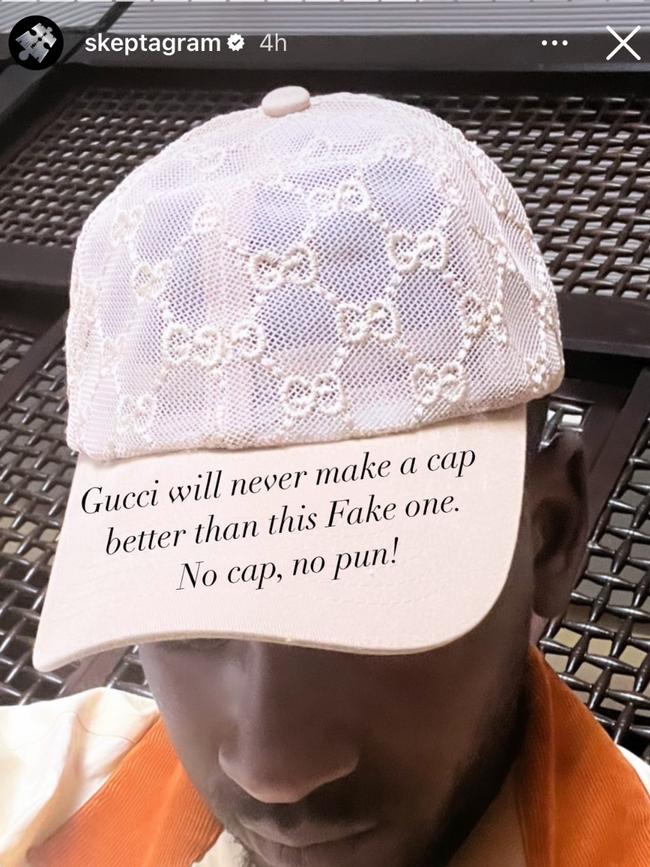

Type the word “Gucci” into Instagram or TikTok and dozens of videos pop up of luxury experts explaining how to spot fake versions of the designer label’s handbags, shoes and clothing.

The Italian fashion house has become one of the most globally counterfeited brands, a problem that has worsened as higher prices fuel the demand for so-called dupes. It has made an indelible impact on the reputation of a brand long known for its high-quality products and distinctive styles.

One luxury fashion enthusiast said they no longer shopped at Gucci as “there are so many fakes around”.

Another said its products had become “too loud” (think yellow pumps and cartoon-emblazoned cardigans) and that she, too, could not see past its fake goods problem. “Any time I see someone wearing it in the street, I just assume it is fake.”

Yet Gucci’s challenges do not stop there. The brand, once the darling of the Kering group, has struggled amid a downturn in the once-booming luxury market and a shift to “quiet” luxury, characterised by a subtler, more refined aesthetic. Kering, which also owns Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent and Alexander McQueen, has been hit harder by this shift than its luxury peers: instead of opting for Gucci’s garish products, consumers have favoured brands such as Prada and Hermes for their more understated offerings. Both have announced higher revenue recently, despite the wider sector downturn.

Analysts at Barclays noted that an increasingly polarised Chinese market had caused further problems for Gucci, where the wealthiest consumers have gravitated toward the exclusivity of some rival brands. On the other hand, aspirational shoppers, typically the driving force behind the label, have retreated, their spending power squeezed by economic pressures.

Revenue at Gucci, from which Kering derives half its sales and more than two thirds of its profits, declined by 18 per cent to euros 2.1 billion in the first quarter of the year as a fall in the Asia-Pacific region weighed heavily. Kering made euros 4.5 billion in sales for the period, down by 10 per cent year-on-year.

The Gucci brand is in turnaround mode as its bosses try to figure out its place in high fashion. There was a management shake-up recently and it has appointed a new creative director, Sabato de Sarno, whose designs began to appear in stores in February. It is revamping its handbags, a crucial category, and has plans to accelerate new launches this year.

However, Kering said the turnaround would take time. The French luxury group expects its operating income to drop by between 40 per cent and 45 per cent in the first six months of 2024 as investments to revive its key fashion brands weigh on profits.

Kering’s recent problems have pushed it even further behind its biggest competitor, the Bernard Arnault-owned LVMH, the owner of 75 luxury brands including Christian Dior and Tiffany & Co. LVMH, considered a bellwether for the wider sector, reported a 3 per cent rise in sales in the first three months of the year.

The dollars 350 billion global luxury sector, which usually is insulated in times of economic stress, has suffered slowing demand in Britain, Europe, China and North America as higher inflation and economic instability have curbed people’s desire for luxury items. Analysts have said the biggest problem is low confidence among China’s middle classes, with people watching their spending more closely. On a global level, consumers have sobered up since the post-Covid “you only live once” spending boom.

It hasn’t helped that brands have raised prices by, on average, 32 per cent since 2019, according to Luxurynsight, a Paris-based luxury data platform. The result is “sticker shock”, the phenomenon of buyers, even well-heeled ones, avoiding expensive products. Michael Ward, the managing director of Harrods, said that “luxury customers might have money, but they aren’t naive”.

Most luxury goods brands have been affected by the downturn, including De Beers, the diamond producer that recently was forced to slash its target for diamond production by more than a fifth. However, some have joined LVMH in starting to report a pick-up in sales growth. Prada achieved net revenue of euros 1.19 billion for the first quarter, up 11 per cent in reported terms year-on-year. The Cartier-owner Richemont, of Switzerland, enjoyed a surge in sales in China in its latest quarter.

The businesses having to fight harder to get back on track are predominantly those facing deeper challenges, according to Luca Solca, a luxury sector expert at Bernstein, the broker. “There is a slowdown and the brands in transition are paying the highest price, like Gucci and Burberry,” he said. “Consumers putting the foot on the brake become more discerning and concentrate their spending on fewer must-have brands. If you’re not in that group, you fall. If you are in that group, you are still all right.”

Burberry, the British luxury retailer known for its tartan check, issued its second profit warning in three months in January after another slowdown in sales. The brand is in the midst of a turnaround as it attempts to move more up-market. Daniel Lee, its chief creative officer, has been working on making Burberry a cooler brand while leveraging its British heritage to woo customers. However, HSBC said the price tags on pieces from Lee’s collections had made fashion followers wince, not great at a time when the general luxury market is experiencing a slowdown.

One luxury retailer, which stocks Burberry, said that “changes don’t happen in luxury overnight. It takes years and I think they’ve got to be clever and not disenfranchise their existing customer base but gradually bring in newness. And that will take a lot of time.”

The online marketplace sector for luxury brands is also having a tough time. Matchesfashion fell into administration last month and in December Farfetch narrowly avoided collapse when it secured a dollars 500 million rescue deal. Net-a-Porter is up for sale and Michael Kliger, the chief executive of Mytheresea, said recently that it was enduring the “worst market conditions since 2008”. Kien Tan, a retail adviser at PwC, the auditing firm, said the question was whether the downturn was temporary or whether the luxury eCommerce model was now “unviable” as shoppers opted for in-person, direct-to-consumer experiences.

As for the future of the global luxury sector, Solca said the industry would remain challenged this year, while “2025 may be a better year, depending on what happens in China and in the presidential election and in the various geopolitical hotspots”.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout