Doris Day’s sunny image hid private woes

Unlike her wholesome on-screen image, Doris Day’s life was frequently sexy, vapid and tragic.

-

Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be) was not only Doris Day’s most popular song but also the theme tune to her life. She was cinema’s most enduring innocent, bubbly as soda, wholesome as apple pie; blonde, blue-eyed and fair skinned. For six years from 1959 she was one of the top box-office draws in American cinemas. Only Frank Sinatra or Bing Crosby could sell a song so well.

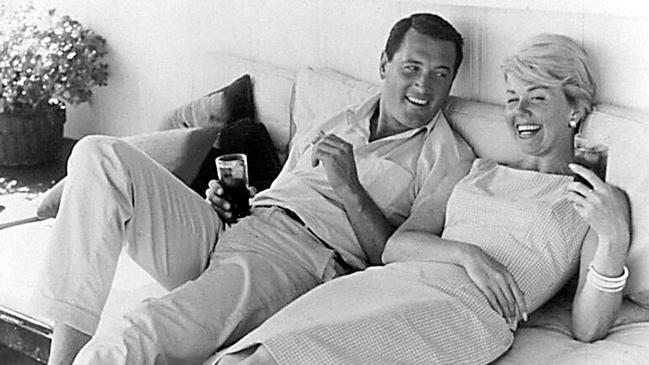

She began her career as a wartime band singer, graduated to Hollywood musicals and later appeared in a run of comedies with Rock Hudson, who called her Zelda or Eunice (she called him Murgatroyd). She had hit records, became a pin-up for the troops, and starred in Romance on the High Seas (1948) and the enjoyable musical Tea for Two (1950). The success of Love Me or Leave Me (1955) — a biopic of Ruth Etting, a singer who had found fame in the 1920s as a torch singer — showed Day in a more beguiling light.

Alfred Hitchcock offered her the lead in his thriller The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) with its song Que Sera, Sera, which seemed to best sum up her fatalistic philosophy. For behind this relentlessly sunny screen image lived an emotional woman who suffered much bad luck in her personal life. She was a serial bride: beaten by her first husband, abandoned by her second, swindled and widowed by her third, and bored by her fourth. She claimed never to have known that Hudson, to whom she was particularly close and who died in 1985, had AIDS. The death of her son in 2004 was a further blow.

Those who knew Day spoke of a woman who, despite being the blonde sweetheart of the silver screen, was refreshingly straightforward.

She worked hard as a dancer and proved surprisingly versatile as an actress, although not for her the Method school; as Spencer Tracy advised, she aimed to know her lines and not bump into the furniture. This made her perfect material when producer Ross Hunter had an idea for Pillow Talk (1959), a sophisticated sex comedy without the sex. The film includes the famous split-screen scene with Hudson and Day in bubble-filled baths in adjoining bathrooms with their feet appearing to touch through the wall.

Pillow Talk was followed by two more comedies with Hudson, as well as comedies with David Niven, Cary Grant and James Garner. There was a thriller with Rex Harrison as a would-be wife murderer in Midnight Lace (1960), when the new Doris Day heroine had a job, an apartment, a couture wardrobe and a lacquered hairstyle. “I think my pictures are sexy,” she said. “But there’s a difference between good, clean, farcical sex and dwelling on sordid themes.”

She was born Doris Mary Ann von Kappelhoff in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1922, although she was prone to shaving a couple of years off her age when it suited. Her father, William, was a piano teacher and organist. Her mother, Alma (nee Welz), was from a family who ran a bakery. She was named after Alma’s heroine Doris Kenyon, the early film star who appeared opposite Rudolph Valentino.

There were two elder brothers: Richard, who died before Doris was born, and Paul, who died in his 30s. William and Alma divorced when Doris was 12. “At 10 years of age, I discovered that my father was having an affair with the mother of my best friend,” Day recalled of discovering him in the act.

Doris began dancing lessons with the Hessler Studio of Dancing at an early age and by 12 was appearing in a Fanchon and Marco stage show; she formed a dance act with a local boy called Jerry Doherty, winning $500 in a talent contest. On the back of this her mother was preparing to move the family to Hollywood, but the night before they were due to leave, Doris, 15, was on a double date with a friend when a freight train hit the side of their car while it was on an ill-marked crossing. She spent 18 months recuperating.

During her convalescence she listened to the radio. Ella Fitzgerald was a favourite and Doris sang along, trying “to catch the casual yet clean way she sang the words”. To ease the boredom she had vocal training from Grace Raine, a coach with useful radio connections. Before she was off her crutches, Doris had her first engagements, with three of the best big bandmasters in the US: Barney Rapp, Bob Crosby and Les Brown. She took the name Day from one of her hits, Day after Day, after Rapp insisted that he could not put the name Kappelhoff on billboards and advertisements.

Unlike her wholesome, innocent on-screen image, Day’s off-screen life was frequently sexy, vapid, tragic, bedevilled and pitiful. She was 18 when she married Al Jorden, a trombonist from Rapp’s band with a penchant for violence, especially when she was pregnant. She stayed just long enough to have a son, Terry, then escaped. In 1946 she married George Weidler, a saxophonist who left after eight months, unhappy about becoming Mr Doris Day.

In wartime America, under the paternal care of Brown, Day chalked up several hit records. Although she had little confidence in her acting, she was persuaded to audition for Romance on the High Seas, a musical directed by Michael Curtiz. He wanted Day to sway her hips to the music. “I don’t bounce around. I just sing,” snapped Day, who spent much of the screen test in tears. Nevertheless, she got the lead role, the film was a hit and Day followed it with Tea for Two.

She also enjoyed singing for films. Unlike on radio or on stage, she could repeat a song until it came out right. She had suffered badly from nerves as a band singer, but in Hollywood that kind of pressure was off. As an actress she began to show her range, starting by stealing the show with her pert smile and sugarcane voice in Romance on the High Seas with Jack Carson, one of her many lovers. Storm Warning (1950), in which she played the wife of a Ku Klux Klansman, was her first non-singing role. Also good was the infelicitously titled Young Man with a Horn (1950), a biopic of jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, starring Kirk Douglas and Lauren Bacall.

Despite the mediocrity of her material, she was well on the way to becoming a big draw when she made Calamity Jane (1953). Here was a vehicle worthy of her talent — a delightful musical that includes the daffodil-filled scene where she sings Secret Love. Women loved Day’s films because she seemed so ordinary, men liked her for being unthreateningly sexy, and directors appreciated her professionalism.

Management of her career was taken over by her third husband, Marty Melcher; she married him on her 29th birthday after briefly dating Ronald Reagan. Melcher knew how to negotiate a deal, dragging her name into business investments, including a hotel chain, oil wells in Oklahoma and property holdings in Hollywood, as well as a cattle ranch. Before long she had suffered a breakdown and told friends that she was dying of tuberculosis and heart trouble, although exhaustion and nervousness were the real causes.

By the start of the 1960s she was the hottest property in Hollywood, making a fortune for the movie moguls while never remotely offending the wholesome values of middle America.

Her last film with Hudson was Send Me No Flowers (1964). It showed healthy returns, but nothing like those for Pillow Talk, for which she had been nominated for an Oscar. Yet by the middle of the decade, Day’s trademark look of wide-eyed horror at any man who made a pass at her now seemed old-fashioned and The Glass Bottom Boat (1967) was her last hit. Day turned down the role of Mrs Robinson in Dustin Hoffman’s classic The Graduate (1967), which might have set her on a new path, although in her memoir Day recalled refusing it on “moral grounds”.

Although she also signed a record deal worth $1 million with Columbia Records, which included an album called Duet with Andre Previn, she rarely saw the money. When she asked where it had gone, Melcher talked mysteriously of “tax shelters”. After his death in 1968, Day was horrified to discover that he had signed her up for a television series. Worse, Melcher apparently had embezzled millions of dollars of her money.

She went ahead with six series of The Doris Day Show but did so under the strain of a new crisis. Her son, Terry Melcher, who had taken his stepfather’s name, was by then a successful record producer. After the murder of Sharon Tate it emerged that Melcher had once refused Charles Manson a recording contract. The murder took place at Melcher’s old address, which was now rented by Tate and Roman Polanski.

Day would insist that she had never had any great ambitions. “My desire as a girl was to get married and live happily ever after, have children, take care of my husband, cook and do all those things,” she said. “I have no drive in me. I turn down one thing after another.”

As if to prove her point, Day finished the television work in 1973 and retired. The next year a Californian judge awarded her $22m in damages from Jerry Rosenthal, Melcher’s lawyer, who had helped with his deception.

From 1975 to 1981 she was married to Barry Comden, who was 10 years her junior and the maitre d’ at one of her favourite restaurants. Critics suggested that she had adopted him, like one of the many stray animals she now took in. Thereafter she concentrated on the Doris Day Pet Foundation, at one time sharing her home in Beverly Hills with 17 dogs. After Hurricane Katrina struck Florida and Louisiana in August 2005, her group was instrumental in airlifting stranded and abandoned animals to safety.

During the 80s, film festivals, retrospectives and seminars were held in her honour. Day declined to attend them, although she did make the odd appearance in documentaries. In 1994 she released The Love Album, which had been recorded in 1967 but never issued. Then, in 2011, she released My Heart, which included previously unreleased recordings by her son Terry, made before his death from melanoma in 2004.

There was much excitement when a rumour circulated in 1988 that she would attend the Oscars. The producers had even procured a dog sitter so she could have no excuse for backing out.

Contrary to the words of her most popular song, however, it was not to be, to be.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout