Digitally made replicas could help Britain return the Elgin Marbles

Cutting-edge robot technology prompts a rethink of how we view rare objects and what their value is, educationally, culturally and in cash.

I recently carried out a blatant act of forgery. Hanging in my cousin’s home in Scone, NSW, is a very large oil painting of Captain Peter Macintyre, the first of our clan to settle in Australia. Painted by James Ramsay in 1825, it depicts my ancestor in full Highland regalia, with a backdrop of Loch Awe, the ancestral lands of the Macintyres.

My father, who left Australia in 1943, often spoke of this painting. I have never seen it, but I have always coveted it. And now, in a way, I own it, thanks to the latest digital technology. Last year my cousin kindly allowed me to have it copied by a professional photographer from Sydney, at the highest possible resolution, using a megapixel camera. The image was then colour-corrected, retouched and edited by Andy Smart of AC Cooper, specialists in art reproduction. It was then heat-mounted on to stretched canvas on a wood frame.

Over several weeks Sharon Smart applied layers of varnish and texture to the canvas, filling in flakes and restoring colour where the original had faded from the heat. We then placed the result inside a huge gilt frame. Such copies are in high demand: from families in which more than one inheritor wishes to retain a copy of a prized painting, to individuals who wish to avoid high insurance costs by displaying a copy while the original sits in a bank vault – or just for the pleasure of owning something that is almost genuine.

Captain Peter Macintyre, in all his tartan finery, now hangs in my home in Scotland: a magnificent, massive, unapologetic fraud. I defy any non-expert to spot, without close inspection, that this is not a 19th-century oil painting. The whole exercise cost me less than £2000 ($3400), which may be rather more than the original is worth. It is not a work of art. It is a very new thing representing a very old thing, but virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. In artistic terms, it is worthless. It gives me enormous pleasure.

This replica is a small illustration of a much wider argument triggered by advances in digital technology and three-dimensional printing. The methods now exist for making a near-perfect replica of any object of beauty, value or cultural significance, raising a host of troubling questions for collectors, artists, connoisseurs, museums, galleries and the art market.

Does this open the way to counterfeiting on a huge scale? Does it undermine the essential idea that an object is valuable and important because it is unique? But does it also open up a way to re-create objects that have been lost, either accidentally or through wanton destruction? Does it prompt a rethinking of what a rare object is for, and what it is therefore worth, educationally, culturally and in cash?

Perhaps most important, the possibility of all-but-undetectable replication opens a new front in the furious battle over whether objects held in museums and galleries should be repatriated.

If an object can be copied, then do ideas of “cultural property”, patrimony and provenance cease to matter? Why not make a perfect copy, keep it and return the original to its place of origin? Or keep the original and offer copies to the claimants? Or make several identical copies and spread them worldwide to anyone who wants them? We do this with books. Why not with other works of art?

Inevitably, the Elgin Marbles have become the focus and lightning rod for these questions, and a test case. The great 5th century BC sculptures and bas-reliefs taken from the Parthenon and other temples on the Acropolis by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, remain the most hotly contested objects in the world: Greece wants them back and the British Museum, seeing itself as the global guardian of such treasures, does not want to surrender them. That debate, which has raged since 1816 when Elgin sold the marbles to the British government, has developed a twist with the arrival of 3D machining, in essence a robot capable of carving precise marble replicas. The Institute for Digital Archaeology, a research consortium based at Oxford, has started replicating the Elgin Marbles with a view to persuading the BM to return the originals to Athens and ending the longest feud in art history.

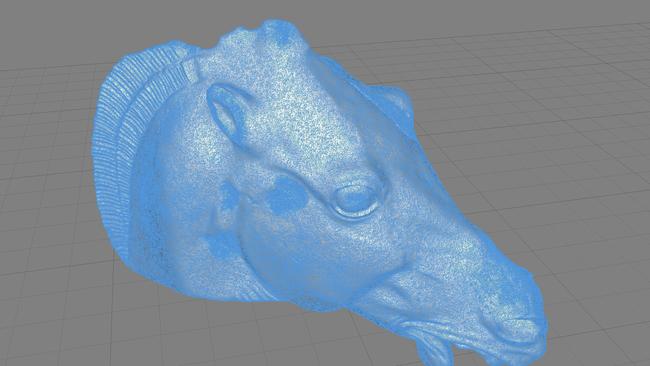

The technology uses special Lidar cameras, which convert light pulses into a spray of infra-red dots producing measurements accurate to a fraction of a millimetre; overlapping photo images are then converted into a precise geometric computer model, and the carving robot does the rest, far faster than any human carver ever could.

“It will be very difficult even for experts to identify the differences between the two once the copies are created,” Roger Michel, director of the institute, told Greek newspaper I Kathimerini. “Visitors to the British Museum will not be faced with an empty wall but will continue to see what their fathers and grandfathers saw.”

That thought scandalises those who believe the essence of an object’s cultural value lies in its uniqueness, but the new Elgin Marbles are coming whether their custodians like it or not. When the IDA requested permission to scan the statues, the museum refused: so Michel and his team simply walked in and took the photographs, using iPhones equipped with Lidar technology. It took the robot four days to reproduce one of the Parthenon marbles, the life-size head of a horse hewn from Carrera marble.

At the end of this month, Michel intends to display this and two other replicas, including one carved from marble quarried on Mount Pentelicus, the stone used to construct much of the Acropolis. The location of this “guerrilla exhibition” remains secret but it will be in a private garden and visible to passers-by within a block of the British Museum.

One of the new marbles may be closer in appearance to the originals than those in the museum. In the 1930s, museum restorers “cleaned” some of the sculptures with wire wool and an abrasive agent, stripping off the beige-brown patina of the outer layer to make them whiter. The IDA has restored some of the original skin colour to one of the replicas, applying paint by hand. While clearly unhappy with the IDA’s challenge, the British Museum had made no move to stop the exhibition of the copies, and it is not clear it has any legal basis to do so: there is no copyright on an object 2500 years old.

The Greek government has not formally responded to the idea of receiving the originals back while the British keep perfect copies, but Michel says he has received encouraging signals from Athens, including a suggestion that parts of the Parthenon still in Greece might be copied and displayed in the UK.

Many historians object violently to the idea of replica marbles, insisting that a copy untouched by the hand of any artist, let alone an ancient Greek one, is of no more intrinsic or aesthetic importance than a postcard from the gift shop.

Some on the Greek side also detect the lingering whiff of imperialism: if Britain does not have a moral right to these objects, how can it insist on keeping copies? If copies are to be made, that is for Greece to decide, not Britain. Yet there are signs that a peace agreement over the marbles, perhaps involving some replication, may be in the offing.

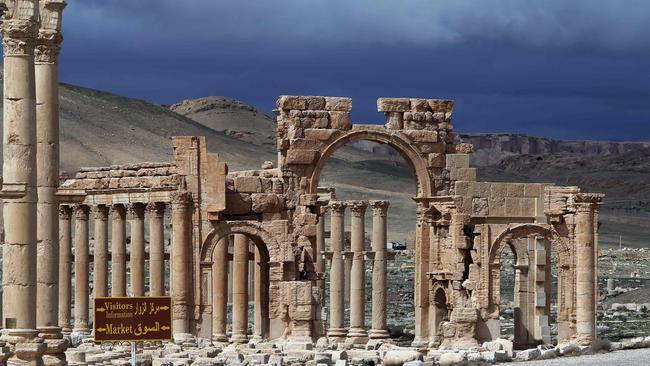

“I think there’s a deal to be done where we can tell both stories in Athens and in London,” George Osborne, chairman of the museum’s trustees, said in June. The deputy director of the British Museum has proposed a “Parthenon partnership” with Greece. In 2016, the IDA created a 6m replica of the Roman Monumental Arch in Palmyra, Syria, destroyed by Islamic State militants a year earlier. The arch, carved in Italy from Egyptian marble using the 3D technology, was displayed in Trafalgar Square before moving on to New York, Florence, Geneva and Dubai. Boris Johnson described the reconstruction as “a triumph of technology and determination (created) in a spirit of defiance, defiance of the barbarians who destroyed the original”.

Yet while re-creating a lost architectural treasure in miniature may send a political message to religious vandals, its artistic worth is more debatable. Great art is by its nature fragile, liable to decay and vulnerable to destruction. When it is gone, it is gone forever, which is why it holds such value for humanity; preserving and restoring an artwork is very different from reproducing or reconstructing it. Nothing can duplicate the experience of an original artwork, an ancient building or monument, or an inspiring sculpture. Standing before the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, you feel the presence of Leonardo. A copy cannot replicate this. The same image bought from Ikea (where it is named, inexplicably, as BJORKSTA) is just wallpaper.

Yet copies have a power of their own, and while we rightly worship the unique, we also value its imitation, and we always have. The Romans copied Greek statuary on a huge scale and claimed it as their own. The 10th casting of a Rodin statue is as bewitching as the first.

Great artists had “schools” to copy and replicate their art; how much of the master’s hand was involved in any given work is unknown. The great terracotta warriors of China are all replicas.

Photography is an art form based on the possibility of infinite duplication. A photo of a Vermeer cannot move us like the painting itself but it can remind us of that emotion. The British Museum itself accepts that replicas are useful and can provide an accurate, albeit synthetic, impression of what the original looked like.

The two galleries adjoining the Elgin gallery contain replicas of Parthenon sculptures that remain in Greece. Visitors do not seem to mind that these are not original, or even notice. But the new technology may aid criminals as much as educators. At present, 3D machining requires too much time, money and expertise to tempt counterfeiters, but as the technology becomes cheaper, the opportunities for forgery will undoubtedly increase.

Object ownership is inextricably associated with nationalism. While British museum directors still insist the integrity of collections must be maintained, in private many admit that the game is up. France has returned objects expropriated from Southeast Asia and Senegal. Cambridge and Aberdeen universities have returned Benin bronzes to Nigeria more than a century after they were looted by British troops. “It is all going to go back,” one director of a major museum told me recently. “It’s just a question of when.” And in what form.

The magic of 3D reproduction may help that process, by blurring the distinction between original and copy, the real thing and replica. We seem to be moving beyond a simple physical conception of art, with non-fungible tokens or NFTs (digital art recorded on the blockchain) and conceptual art in which the value of an artwork is the idea behind it, not the object itself.

Perhaps we are approaching an age when it no longer matters who holds the original, or where. When a machine can knock out an Elgin marble in a few days, the idea of museums as national custodians of culture may be anachronistic. A replica will never supplant an original art object but might instead supplement it, and spread its influence; just as every library should contain the great works of literature, perhaps every school might one day display an Elgin marble, along with an explanation of where the original came from, where it resides, and how and why it has been copied.

The digital revolution has altered our relationship with so many physical things, and that may be increasingly true of great art.

We are happy to join our fellow human beings in a virtual world, so why not also celebrated treasures? Far from diminishing the power of the original, the availability of cheap, easily reproduced copies might increase interest in museum artefacts. For some people, notably children, a museum visit can be a daunting experience: heavily guarded objects in the distance that may not be approached. What better way to discover the Elgin Marbles than being invited to touch an authentic replica?

Art forgery, though, is already big business, and the development of ever more sophisticated digital replication technologies will rattle an art market rendered paranoid by a flood of recent frauds.

Sotheby’s New York recently established a forensic department to carry out scientific tests such as paint analysis to buttress the opinions of experts. While copying an ancient oil painting requires expertise, photomechanical reproduction has led to a surge in fake prints hitting the market, with Lichtenstein and Warhol the most frequently forged artists.

The arrival of digital 3D reproduction invites a different sort of relationship between the object and the observer, in which the replica does not claim to be the original but instead an echo, and the observer knows it. Venerable and vulnerable physical things are vital to civilisation because they tell us human stories of the past; a copy can never duplicate this, but it can help, particularly when rival nations or individuals claim ownership of a single article. My copied painting of Peter Macintyre also tells an odd story: he did not really dress like that. In 1822, George IV visited Scotland, the first reigning monarch to do so in more than two centuries; Sir Walter Scott was brought in to invent a pageant presenting a romantic vision of ancient Scotland, in bold tartan. The king himself was painted in full Highland garb.

The man deputed to welcome the king when he landed at Leith was Captain Macintyre, the leader of the Drummond Highlanders, dolled up in bright red tartan and equipped with weaponry including dirk, sword and pistol. This was how Ramsay depicted him: the painting is really a fashion plate, a slice of imaginative sartorial political propaganda. My replica makes no claim to be anything but a fabrication, and that is why I love it: an intriguing artistic fraud, depicting an intriguing artistic fraud.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout