Coronavirus: The age of pandemic is upon us

The death rate of COVID 19 is just 2 per cent. The Spanish flu, which killed 50 million, had the same low mortality rate.

The stories tend to begin the same way: with a lone scientist and a warning. There in the laboratory, they look down the microscope. They look up, perhaps rub their eyes, then look down again. Then, having confirmed their worst fears, they rush to the phone to tell their superiors they have found a disease unlike any other.

Of course no one listens to this Nostradamus in a lab coat, but in the weeks and months to come they will wish they had. From Stephen King’s The Stand to Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, the plot progression of a virus outbreak in fiction is the same. First, hospitals are overwhelmed, then the government tries to cover it up, then society finally breaks down.

Back in the real world, a world that is panicking but not exactly yet at post-apocalyptic fiction levels of panic, real scientists have also been issuing warnings for a long time. In 2018 at Davos, Sylvie Briand, an infectious disease specialist at the World Health Organisation, said the next great pandemic was coming, that we were more vulnerable than ever, “and we have no way to stop it”.

Last year, a scientific committee attached to the World Bank warned that there was an “acute risk for devastating regional or global disease epidemics that not only cause loss of life but up-end economies and create social chaos”. And that’s only the past two years. Nobel prize-winning biologist Joshua Lederberg puts it more bluntly. “The single biggest threat to man’s continued dominance on this planet is the virus.”

All these prophets of doom, true to the demands of apocalyptic fiction, have been ignored. Today, though, they are being listened to. Today in the Chinese city of Wuhan, hospitals are overwhelmed, the government is accused of a cover-up and society is teetering. Is this the great pandemic long foretold?

The only sensible answer, an answer that is actually a lot more comforting than it should be, is no.

The death rate from the new coronavirus is low, at 2 per cent, but that, to an extent, misses the point. It is entirely possible that the worst imaginings Lederberg will never come to pass, that the true viral apocalypse will never arrive, that for years to come we will still be telling the Nostradamuses they were wrong.

The strange thing is that if, as many experts believe, the spread of COVID-19 is unstoppable, 2 per cent should not be at all comforting. A small percentage of a very big number is still a very big number indeed. These days, small percentages of big numbers routinely scythe their viral way through the world’s population but do so, unlike in the novels, almost unnoticed. Because in looking for the apocalypse we have missed a more subtle truth. We are not waiting for the age of the pandemic — we are deep in it, and we are still unprepared for what that means.

Bugs from birds

In France, probably in 1917, a virus mutated. This virus had lived for eons in birds, following them as they migrated above Europe. It was no more harmful to them than a cold is to us. The 1917 mutation changed this. It allowed the virus to do the most interesting thing it had done for many millennia: jump species. Below, crammed together within coughing distance, were millions of men who were about to demobilise, in a human migration the scale of which had rarely been matched.

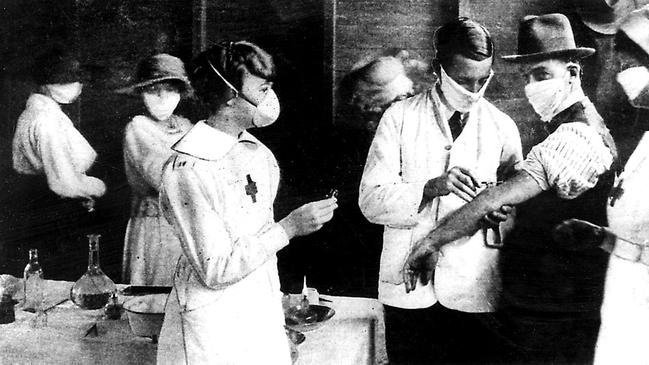

Finding a home among them, accompanying them on their home journey, the virus appears to have experienced a second mutation, allowing it to spread not just from bird to man but from man to man too. In two years, that virus wrought more death than could be achieved by the determined efforts of the gas, guns and tanks of the world’s most advanced powers in the four years previously. Perhaps 50 million died; about 15,000 in Australia. It had, by the by, a death rate of just over 2 per cent.

You know that story but do you know about the Asian flu outbreak of 1957? Between one million and two million people died. Eleven years later, the Hong Kong pandemic caused twice as many deaths. In the past 20 years we have had severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola and Zika.

In 2009 H1N1, also known as swine flu, infected as many as one in five people on the planet and killed as many as 500,000. Which sounds a lot until you realise that each year, without comment, 200,000 to 700,000 people die from common or garden flu. Small percentages add up.

“If this was a conventional war,” says Robin Shattock, a virologist at Imperial College London, “people would invest long-term in military forces to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” The age of the pandemic is upon us. And, given our modern habits, that should not be surprising.

In the second century AD the Roman physician Galen reported a terrible plague. There were ulcers, blisters and mass death. Thousands, it was said, died each day. Some believed it to be the end times. What is now called the Antonine Plague spread, though, not because of deadly curses but because of something more mundane: roads. Thanks to Roman transportation it had soon reached every corner of the most connected empire the world had seen.

Mixing always brings disease. Mixing along the Silk Road brought bubonic plague to Europe. Mixing with animals, domesticated during the agricultural revolution, brought animal diseases to humans. Never before have we mixed so fast or so often.

During the SARS outbreak, 17 years ago, there were about 20 million flights a year. Today there are twice as many. Two million Muslims go on the annual hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, while three billion journeys are made over Chinese New Year.

“We’re living in a highly globalised and mobile world and seeing the consequences of this,” says Andrew Tatem, from the University of Southampton. “Back in the 1300s, it took around 15 years for bubonic plague to spread from China to Europe; in the 1918 influenza pandemic it took many months for global spread to occur; today we’re seeing global spread in a matter of days and weeks.”

The first great paradox of pandemics is that technology and progress normally make us better able to cope with disease. With viral outbreaks, progress itself is the problem. “Our lifestyle, our technology, is all speeding up,” says Jennifer Rohn, from University College London. “It becomes a cat-and-mouse game and it’s hard to know who is going to win. On the one hand things spread faster. On the other, we have an unprecedented ability to respond.”

She is not certain that technology will prevail. “I always tend to think the bugs win. They were there long before us.”

“Winning”, for a bug, is a complicated concept, though. And this leads to the second great paradox — that more deadly viruses do not make for more deadly pandemics. A virus is not malevolent. It is the purest form of life there is. It has no cell, no brain and no will. It is a reproduction machine, a sliver of genetic material inside a protective shell, whose sole purpose is to make copies. It does not want to hurt you, it wants to use you. It is not good for it if you die. Corpses, after all, don’t sneeze.

This is why the “worse” a virus is for individual humans, so the conventional logic goes, the less likely it is to be of concern for humanity. If it causes instant death, it ends with the first victim. If it causes a mild sniffle it conquers the world. If it does kill widely, then it needs to kill slowly for you to find another victim to pass it to. This is why Ebola will probably never gain a foothold in Europe. “It’s too conspicuously deadly,” says Rohn. “When we see people bleeding out of their eyes all our ancient contagion instincts kick in.”

What worries scientists is if a virus mutates so that the old trade-off of virulence versus spreadability no longer applies. You notice bleeding eyes, says Rohn. But coughing and sneezing? “It’s so generic, it could be anything.” If she were a deadly virus and looking to spread, that is how she would do it. “In the old days, when we lived in villages in the jungle, (a very deadly virus) is not going to spread. But imagine a respiratory virus with a two-week incubation period. Imagine someone coughing in Heathrow Airport …”

More to worry about

Last month Steven Chu, head of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, imagined something like that. He was asked what worried him about the COVID-19 outbreak. He responded by talking about a different outbreak, one that is still occurring largely unnoticed to the south of Wuhan. There, in farms where chickens are packed wing to wing, an avian flu called H5N1 has learned how to infect humans.

“This is something even more worrisome, if you’d like to worry,” he said. “If you get it you have a 60 per cent chance of dying.”

It has not — yet — learned how to spread from human to human in a sustained way but if it did, argued Chu, “this is big-time serious stuff. You’re talking about a fraction of the world’s population”.

Ultimately, says Adam Kucharski, an academic at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and author of The Rules of Contagion, it’s a race. “The question with any new outbreak is whether collaboration is enough to outpace contagion.”

There has been a parallel story throughout the rise of coronavirus, which has been the deployment of long-planned scientific responses. During the SARS outbreak scientists were secretive about their data, hoarding it so that the best journals, which insist on exclusivity, would still want to publish it. During the COVID-19 outbreak all the major publishers have promised that posting data openly online would not jeopardise future publication.

Hundreds of open-access papers have followed. None, though, is as momentous — or as indicative of the revolution that the field has experienced in the past 20 years — as the one that appeared on January 10. Titled Wuhan Seafood Market Pneumonia Virus Isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, Complete Genome, it contained 30,000 apparently jumbled letters.

During the SARS outbreak it took five months to isolate the genetics of the virus and then sequence it. With COVID-19, here in this paper was the whole genome with all the secrets of the virus there to decode, available to everyone within days. When that paper appeared, the funding was already in place for teams around the world to begin work on a vaccine.

Robin Shattock, from Imperial College London, leads one of them. Scientifically, he says, the response to COVID-19 has been unprecedented. It took 15 years to develop a vaccine for Ebola. The chances are that, in a little over a year, someone will have one ready for COVID-19. That is a landmark achievement and also not that useful. What we need is a vaccine now; a lot can happen in a year. It is even less useful when you consider that after making it we still need to be able to mass-produce it.

“Proving something works within a year is doable,” says Shattock. “It’s the scaling up that is hard. We need hundreds of millions of doses.

“This episode should be a wake-up call for government. It is inevitable these things are going to happen more. We live in more and more densely populated environments, encroaching more and more on to natural environments where animals hang out. When you think about not just the human aspects, but the impact on the global economy, it is massive. We need long-term investment.”

This, he realises, is the time to ask for investment. “Right now there’s a surge of ‘let’s do something’.” He knows, though, that the window for politicians to listen to the scientific Nostradamuses is a short one. “Soon, the world will surge on to the next world crisis.”

Meanwhile, in a cave somewhere, in a bird somewhere, a virus is waiting. It has time on its side. All it needs is the right mutation.

The Times

-

Death toll from past pandemics

HIV-AIDS (PEAK 2005)

Death toll: 36 million

Between 2005 and 2012 the annual global deaths from HIV-AIDS dropped from 2.2 million to 1.6 million.

ASIAN FLU (1956-58)

Death toll: Two million

Spread from Guizhou province in China to Singapore, Hong Kong and the US.

SPANISH INFLUENZA (1918)

Death toll: 20-50 million

Followed demobilised troops home from World War I.

SIXTH CHOLERA PANDEMIC (1910-11)

Death toll: 800,000+

Like its five previous incarnations, the sixth cholera pandemic originated in India before spreading to the Middle East, North Africa, eastern Europe and Russia.

THIRD CHOLERA PANDEMIC (1852–60)

Death toll: One million

The deadliest of the seven cholera pandemics. British physician John Snow tracked cases of cholera in London, identifying contaminated water as the problem.

THE BLACK DEATH (1346-53)

Death toll: 75-200 million

Cause: Bubonic plague

Bubonic plague ravaged Europe, Africa and Asia. Probably jumped continents via the fleas living on rats aboard merchant ships.

ANTONINE PLAGUE (AD165)

Death toll: Five million

Possibly smallpox or measles brought back to Rome by soldiers returning from Mesopotamia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout