Child’s play: the publishing phenomenon Jack built

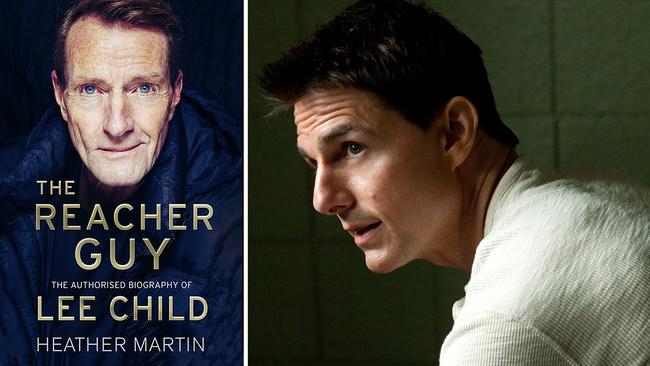

In 2016, the year a miscast Tom Cruise starred in a second Jack Reacher film, Lee Child claims he made $30m. But even his friends admit the author may be as much a creation as his famous character.

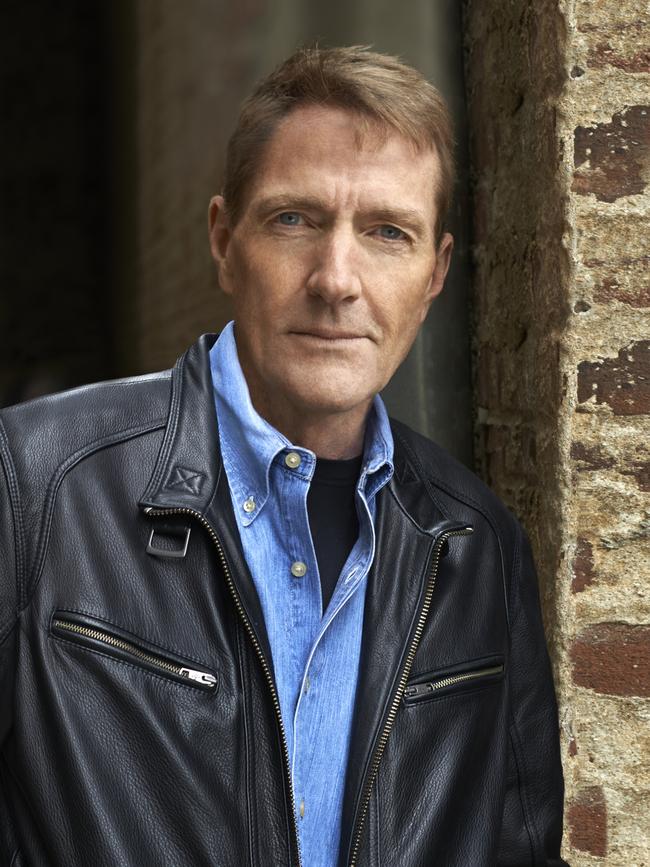

In 2016, the year his 21st Jack Reacher novel was published, Lee Child made 90c a second. Which is almost $30m. That’s if you believe every word the author tells his biographer in this exhaustive, authorised account of how a Midlands-born English scholarship boy called Jim Grant became a Manhattan-based publishing sensation called Lee Child.

Should we believe Child? It hardly rings false. That was the year of the second Reacher film, with a miscast Tom Cruise as the supposedly hulking American military policemen turned drifter.

Child has sold more than 100 million of his 24 novels. And The Reacher Guy also mentions his four New York apartments in the same block — one to live in, one to work in, one for his wife Jane, and one for guests — his ranch in Wyoming, his acres in Sussex, his watch collection, his cars, his philanthropy.

“It’s good to be king,” he tells his biographer Heather Martin.

One of the more interesting strains of this book, though, is the extent to which both Lee Child and Jack Reacher are creations. Did young Jim really beat up childhood rivals with the same brutal nous that he would later bequeath to Reacher? Did he really lose his virginity, aged 14, to two sisters on the same weekend that he discovered marijuana?

The author does speak to friends from Child’s schooldays and his time as director of presentation at Granada Television, where he was responsible for the way all Granada content, including ads and trailers, appeared on screen. The detail guy.

The friends are awed by his confidence, but also point out a penchant for porkies. “I think Jim’s attitude was, ‘If I say something about myself it becomes true because I’ve said it’,” a colleague says. “The actual truth is an afterthought.”

Truth and fiction may get blurred now and then, but future biographers will be hard pushed to outdo Martin for detail. You’ll emerge from the first 300-odd pages knowing more about Child’s formative years that you do about your own.

James Dover Grant was born in 1954 in Coventry, the second son of four children, before moving to Birmingham, where he attended King Edward’s grammar school. He found his father, Rex, a civil servant, indifferent; his mother, Audrey, hostile. He is a gannet for facts, a compulsive reader; unbeatable, he insists, at Trivial Pursuit.

He thanks his tyrannical physics teacher for teaching him how to write in a way that is “brief and concise”. He thanks his wife, a New Yorker, for helping him to name his hero. One day they went to do the shopping, and someone asked the 193cm Child to reach something on a top shelf. “Well, if this writing gig doesn’t work out you can always be a reacher in a supermarket,” she joked.

Made redundant after 18 years at Granada, he approached becoming an author as both creative release and pure commerce. He found out that almost two thirds of bestselling authors’ names began with a C: Christie, Chandler, Clancy, Coben, Connelly, Cornwell. “People browse from the left, but they get bored very quickly.”

The best chapters are when Martin details Child’s incredible focus as he began his second career. He pared away at his writing, accepting input from editors in a way that he later wouldn’t countenance, cutting the length down by more than a third.

Who was he writing for? He loved thrillers. Reacher’s sense of dislocation and disillusion was his own after being made redundant, yet he set out consciously to appeal to “powerless, unconfident readers who would secretly like to enact fantasies — eg survive outside of a job, beat up their foes, be unafraid etc etc”.

Child, now 65, has readers including fellow authors such as Haruki Murakami, Philip Pullman, Malcolm Gladwell and Margaret Atwood; all wowed by the way he makes sure that, as Pullman puts it, “nothing comes between the reader and the story”.

Child has handed over Jack Reacher to his younger brother. The new novel, The Sentinel, is by Lee Child and Andrew Child. The terse style is, as his publisher points out, “quite easy to mimic”. Will Andrew soon be earning 90c a second?

Or is Reacher just a ludicrous set of tropes — he’s invincible! He’s all-knowing! He can’t move five feet without stumbling into an adventure! — without his creator’s animus? Millions of us powerless readers are desperately keen that the new Reacher guy will be able to keep the unputdownable revenge fantasies coming.

— The Times

Dominic Maxwell is a critic at The Times.