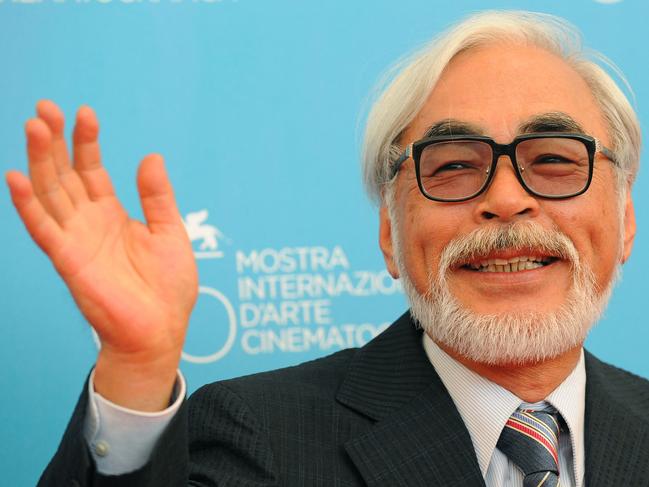

Hayao Miyazaki: Bird’s-eye preview marks magic of greatest animator

Reclusive Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki has released what may be his final film for Studio Ghibli, and it’s already breaking records.

When the world’s greatest animator, Hayao Miyazaki, came out of retirement in 2016 to direct one last film, it looked on the face of it like the marketing opportunity of a lifetime. The 82-year-old Miyazaki enjoys a unique international popularity. Adored by children, adults and film critics all over the world, he is a director whose films have inspired theme parks and lines of soft toys, but who is also the object of intense and earnest intellectual scrutiny.

His 2001 masterpiece, Spirited Away, won an Oscar and was for a long time the most commercially successful Japanese film of all time. His new animation, The Boy and the Heron, the first for a decade, could have been the occasion of a media blitz, with teaser campaigns, viral marketing, trailers and interviews. Late last year, a mysterious poster was released, the close-up sketch of a sinister bird with two sets of eyes. After that – nothing.

When the film opened in Japan in July, no one who entered the cinema knew anything about it at all, except its title. “No trailers or TV commercials at all. No newspaper ads either,” says Toshio Suzuki, Miyazaki’s producer and the president of his production company, Studio Ghibli. “Deep down, I think this is what film-goers latently desire.”

In its first weekend The Boy and the Heron made 1.83 billion yen ($19.3m), the biggest opening in Ghibli’s history; on Imax screens, it set a new three-day record for Japan. No meticulously strategised PR campaign could have achieved more. “In my opinion,” Suzuki says, “in this age of so much information, the lack of information is entertainment.”

For almost 40 years, Miyazaki, with the aid of the brilliant Suzuki, has been achieving the highest artistic and commercial success with seemingly perverse, wilful decisions. He refuses on principle to make sequels. He refuses to allow edits to make his films more accessible to international audiences.

For years, he resisted large-scale merchandising – the Ghibli theme park that eventually opened last year near the city of Nagoya is eccentrically low-key and understated without a single rollercoaster or ghost train, and hugely popular. In an animation industry dominated by computers, Miyazaki still draws largely by hand.

He has resisted both the influence of Disney (“I hate Disney’s works,” he said. “They show nothing but contempt for the audience”) but also the mainstream Japanese animation industry or anime (“to me, the word ‘anime’ only symbolises the current desolation of our industry”).

Most importantly, he has bridged the gap between children’s and adult entertainment, creating films that appeal to kids, but that handle the biggest and most serious of themes.

Miyazaki films such as Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke and My Neighbour Totoro became part of the experience of growing up across the world. The Royal Shakespeare Company adapted Totoro as a stage play, which returns to London this Christmas after a sold-out run last year, and a Japanese theatrical version of Spirited Away will transfer to the London Coliseum next year.

But for all their beauty and the innocent charm of the characters they depict, Ghibli films are deeply concerned with grief, war, environmental destruction and the danger and promise of technology. Now, after six previous announcements of his retirement, Miyazaki has delivered what promises to be his final work.

He was born in 1941 and was evacuated from Tokyo to escape the fire bombs that devastated the city. Scenes of large-scale disaster, natural and man-made, whether by bombing, earthquake, fire or flood, are to be seen throughout his work, from the tsunami in Ponyo to the 1923 Tokyo earthquake in The Wind Rises. The war was a personal matter: his father, with whom Miyazaki had a difficult relationship, ran a company that made parts for fighter planes. As a young man at the elite private Gakushuin University, Miyazaki was part of the post-war peace movement, but his left-wing politics were given an ironic edge by the fact his family owed its affluence to Japan’s wars of imperial aggression.

The sophistication of his films lies in their refusal to adopt the simple moral oppositions that he found so objectionable in Disney. Rather than beautiful princesses and ugly witches, heroes and villains, black and white, Miyazaki sees shades of grey – or rather green. The teeming, vibrating energy of the natural world – forests, oceans, rivers and rice fields – and the threat of environmental pollution are his great theme. There is more concentrated artistry in his renderings of trees and rice fields, or the wings of aeroplanes, than in the flat and simple faces of the human beings who move among them.

Having gone into it completely cold, the Japanese film-going public still doesn’t seem to know what to make of The Boy and the Heron (its Japanese title translates as “How Do You Live?”, which is a famous 1937 novel with no resemblance to the story told in the film). It is as visually rich as anything Miyazaki has produced, but with a meandering story.

It begins with unforgettable flair and drama in showing the firebombing of Tokyo at the height of World War II. A boy, Mahito, runs frenziedly through the flames in a hopeless search for his mother. Months later, he is living in the countryside with his father, a shallow and materialistic man, who builds planes for the Japanese air force. With suspicious speed, he has remarried his dead wife’s sister, who is already pregnant. Mahito’s misery at the domestic situation is intensified by bullying at his new local school, and by the army of grotesque elderly maids who tend to the wealthy family.

Meanwhile, a malign talking heron (the bird image from the poster) torments the boy by telling him his mother is still alive. When his aunt-cum-stepmother disappears, Mahito goes in search of her, following the bird creature into an underworld where he encounters carnivorous parakeets, a young fire witch and an old man who maintains the order of the world by balancing blocks in a precariously wobbly tower.

If this is Miyazaki’s last film, then Ghibli seems doomed to become little more than a licensing enterprise, handling merchandise and spin-offs, such as the London Coliseum production of Spirited Away. But in a country of record-breaking longevity, Miyazaki appears to be healthy – and his efforts to leave the scene in the past have never succeeded.

“Many of you must think, ‘Once again’,” he said the previous time he announced he was stepping down. “But this time I am quite serious. This will never happen again.”

That was 10 years ago. In a life of prodigious success, the one trick Hayao Miyazaki has never pulled off is closing up shop.

The Times