Audrey Hepburn documentary captivates a new generation

The beautiful star's trauma, divorce and heartbreak are laid bare in a revealing new film.

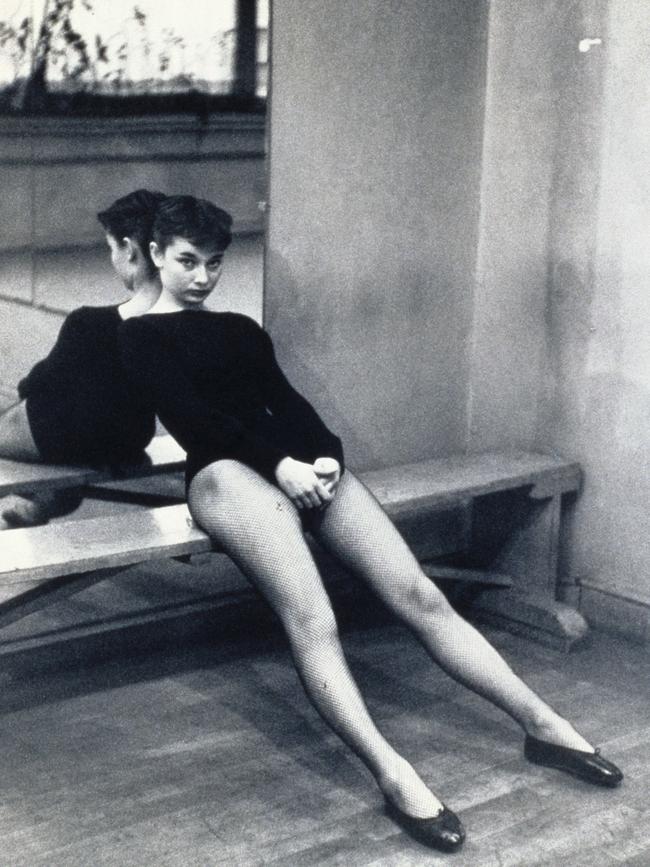

If Audrey Hepburn’s dream had come true, she would have been a ballerina like her idol Margot Fonteyn, but it wasn’t to be.

Instead Hepburn lived another kind of dream and became an idol herself.

In 1999 the American Film Institute unveiled its list of the greatest female screen legends of classical Hollywood cinema. Hepburn was No 3 — behind Katharine Hepburn (no relation) and Bette Davis. She had packed most of that greatness into just two decades, from Roman Holiday in 1953 (she won the best actress Oscar for playing a princess gone AWOL) to Wait Until Dark in 1967 (for which she was nominated for the best actress Oscar for playing a blind woman terrorised by criminals, one of her best performances).

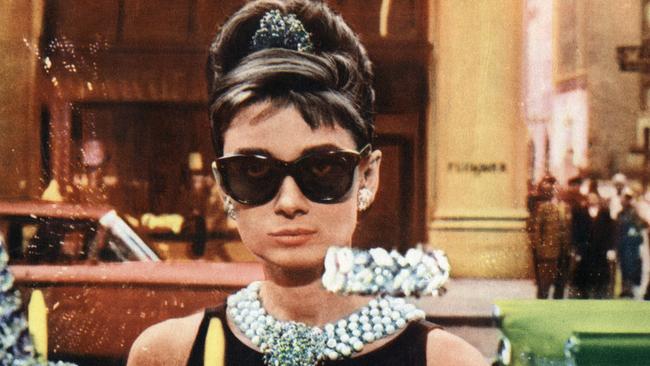

Between came memorable films such as Sabrina (she plays a chauffeur’s daughter wooed by Humphrey Bogart); Funny Face (a photographer’s model); The Nun’s Story (a conflicted servant of God); Breakfast at Tiffany’s (the ultimate goodtime girl); The Children’s Hour (a teacher victimised by slander); Charade (in which she sparks off Cary Grant); and My Fair Lady (in which her singing voice was controversially dubbed).

Hepburn died of cancer in 1993 at the age of 63, having turned her back on Hollywood in the 1970s, devoting her life to family and humanitarian causes with the odd film here and there.

Yet a new documentary about her life suggests that far from being buried in history, the actress is still relevant to a generation that was born after her death.

“From the amount of Instagram messages I get from young women she’s still in our public consciousness,” says Helena Coan, the 26-year-old director of Audrey, the feature-length documentary being released this month. “Young women similar in age to me are interested in her; they still love her and idolise her. Kim Kardashian once did a whole photo shoot dressed as Audrey Hepburn.”

Hepburn had one of the most distinctive looks to grace the silver screen — pencil thin and boyish of frame (in that she prefigured Twiggy in the 1960s), with beautiful big eyes, a 1000-watt smile and a gamine glamour that made her one of the most enduring fashion figures of the 20th century.

Her screen presence combined innocence with high style, elegance with a wide-eyed charm. She enjoyed a close collaboration with French fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy, who gilded her image by placing her in that famous little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Amazingly, though, the woman who wore his clothes so magnificently wasn’t always happy when she looked in the mirror.

“She said she wanted to be a blonde, to have curves and smaller feet and change everything about herself,” Coan says, on the phone from her home in London. “And yet she revolutionised the way women could look. With her short dark hair, her dark eyes and her tall, slim frame she paved the way for a different type of woman.

“She wasn’t a sexualised creature, which is why I think she is often more popular with women than with men. I’m sure she was a sexual being, as every woman is, but it wasn’t part of her makeup as a star. She stood for innocence, she was a very pixie, elfin-like woman. She didn’t exhibit her sexuality in the same way other women did. But she had this power. She stood for love and kindness, and that’s what keeps her going in the public domain.”

Love, as this intimate, sympathetic documentary suggests, was the driving force in her life. Or, more accurately, the lack of it.

She was born in Brussels in 1929 into a privileged family with a Dutch mother (a baroness) and a British father (a keen supporter of fascism). When Hepburn was a very young age, in what she called “the most traumatic event of my life”, her father suddenly abandoned the family.

During World War II, Hepburn was stranded with her mother in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands, where she experienced first hand the Dutch famine, having to eat tulip bulbs ground into flour to survive.

“She was six when her father left and she didn’t see him again until 25 years later when she tracked him down in Ireland, only to receive a chilly reception,” Coan says. “Her father cut himself off from her. He never gave any explanation, just upped and disappeared. It left her insecure for life.

“She was searching for love always and she looked for it in men and it led her down a difficult path. Her mother worked hard for Audrey, but she was not very affectionate and was very harsh to her. Audrey was constantly looking for comfort and safety in her life.”

Hepburn’s first marriage was to American actor Mel Ferrer — they had one son together, Sean, but divorced in 1968, when she broke free of his dominance.

Her second marriage, to Italian psychiatrist Andrea Dotti, also produced a son, Luca, but Dotti humiliated her for years with his relentless infidelity. A mature Hepburn talks about her personal demons in the documentary.

“I struck gold when I found a two-hour-long interview that had never been heard before in which she talked about her dad leaving and her divorces,” Coan says.

“American journalist Glenn Plaskin happened to record his interview with her near the end of her life. I had never heard her talk so candidly about the things she struggled with and the way they affected her, and the way that her father leaving had left her insecure for life. It was a hugely vulnerable thing to say to a journalist.”

Along with archive footage of other Hepburn interviews (some in fluent French, some in her clipped English accent) and some delightful home movies and newsreel shots, there are scenes from her best-known Hollywood films and some enchanting early excerpts from her nascent screen career in Britain which, although not memorable, did lead to her being cast in the 1951 Broadway production of Gigi in the title role.

Audrey also features interviews with the actress’s friends and family. “Audrey’s friends are so protective of her,” the director says. “She did lead a very private life and it was hard to reassure people that you can tell the truth and it doesn’t mean making it tabloid-y or sensational. I wanted to show that her vulnerability was her strength and hers doesn’t have to be a story like Marilyn Monroe who self-destructs because of her vulnerability.”

Among those Coan interviewed on camera were Hepburn’s son Sean and her granddaughter Emma. “We wanted to work with Sean especially because she said Sean was her best friend — they were exceptionally close. He was the one in charge of her medication and changing her dressing. He would sit in a chair by her bed and they would talk about things in the middle of the night. When Audrey died he was at her bedside.”

Her other son, Luca Dotti, is noticeable by his absence. Coan did not approach him for the documentary. “Luca? We never dealt with Luca. It’s public knowledge that the relationship between Luca and Sean is complicated.” So complicated in fact that a dispute between the brothers over Hepburn’s intellectual property rights — the use of her name and likeness — ended up in a California courtroom, where a judge ruled in Sean’s favour last year. The family fallout is not mentioned in the film.

What gives the documentary its distinctive feel is Coan’s decision to blend dance into the narrative. There is a darling clip of a young Hepburn dancing en pointe in the 1951 British film Secret People and a later clip of her hoofing it with Fred Astaire in Funny Face. All good fun, of course, but a far cry from Covent Garden.

Hepburn’s original ambition was dashed when pioneering teacher Marie Rambert, with whom Hepburn studied in London, told her she would never make it as a ballerina because her training was too patchy and too late — the war saw to that. Still, she never lost her love of dance and in later years looked so uncannily like Fonteyn that one is tempted to think the actress modelled herself on the celebrated British ballerina.

In a bold move, the documentary uses three dancers — and Wayne McGregor’s choreography — to reflect the three stages of Hepburn’s life and give her story some emotional heft in the all-too-brief dance excerpts. Young dancer Keira Moore portrays the actress as a child being abandoned by her father; Francesca Hayward is the Hollywood-era Audrey; and Alessandra Ferri represents Hepburn in later life, the selfless humanitarian.

“I love dance and I’ve never seen it used like this in a documentary,” Coan says. “Dance symbolises everything she stood for — beauty, grace, elegance and poise. Also, if she saw herself being represented by dancers I think she would love it. This is like giving her dream a second chance.

“But, yes, there was pressure to cut some of the dance. There were questions about whether it was working properly and what if people wouldn’t understand it or like it. We had to make sure the film was accessible to everyone and I didn’t want to isolate people who aren’t dance fans.

“The last dance sequence is longer than all the rest of them, it’s the finale of the film — literally — and it’s the story of the three dancers together. I pushed for that as much as I could because it was inspired by something Audrey said on her deathbed. She said she could see people sitting at the end of the bed and waiting for her. I like to think it was her past selves who were waiting.”

In the 1980s Hepburn found a peace of sorts, living in a converted 18th-century farmhouse in Tolochenaz, Switzerland with Dutch television actor Robert Wolders and fighting for a better life for the world’s impoverished children in what may have been her most cherished role — as a globetrotting UNICEF goodwill ambassador. “She understood very deeply what these children needed because she almost died from severe malnutrition in Holland,” Coan says. “She knew what it was like to be a starving child. She turned the awful traumatic experience of surviving the war in Arnhem and used that to give life back to children.”

The Times

Audrey is available on DVD and digital download from iTunes on December 16.