The new race to reach the moon – and find water

Renewed ambitions for scientific research and deep-space exploration has sent nations and private companies racing to send devices to the surface of the moon. Sticking the landing is another story.

Nations and private companies are racing to send devices to the surface of the moon. Sticking the landing is another story.

A surge in missions planned for the lunar surface is unfolding around the world, driven by renewed ambitions for scientific research and deep-space exploration. Many aim for the moon’s south pole, where scientists first detected hints of water ice in 2008 and 2009.

Water is a critical resource for a future lunar base – it could one day be used for drinking and cooling equipment, or even to make rocket fuel to power missions to places further away in the solar system, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Tapping natural lunar resources could mean future spaceships wouldn’t have to lug fuel from Earth.

“Water is the key for many aspects of living on the moon,” said Csaba Palotai, an associate professor of planetary sciences at the Florida Institute of Technology. “And the suspicion is that there’s lots of it – that’s why we’re going through these missions to verify how much, exactly, there is.”

The presence of water at the lunar south pole is also raising concerns about how such resources may be claimed. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson recently said he didn’t want to see China land crews on the south pole first and claim water resources there. China has said that space exploration should promote development for all countries and benefit all humankind.

Researchers have confirmed water exists on other parts of the moon, including both the sunlit and shadowed surfaces.

Humans first successfully landed hardware on the moon in 1966, when the Soviet Union’s Luna-9 device touched down. Three years later, U.S. astronauts walked on the moon.

National and private-sector efforts, with improved technology, now aim to put more rovers, landers and astronauts on the moon to conduct experiments and explore. The lunar south pole’s shadowy surface adds to the challenge of landing there.

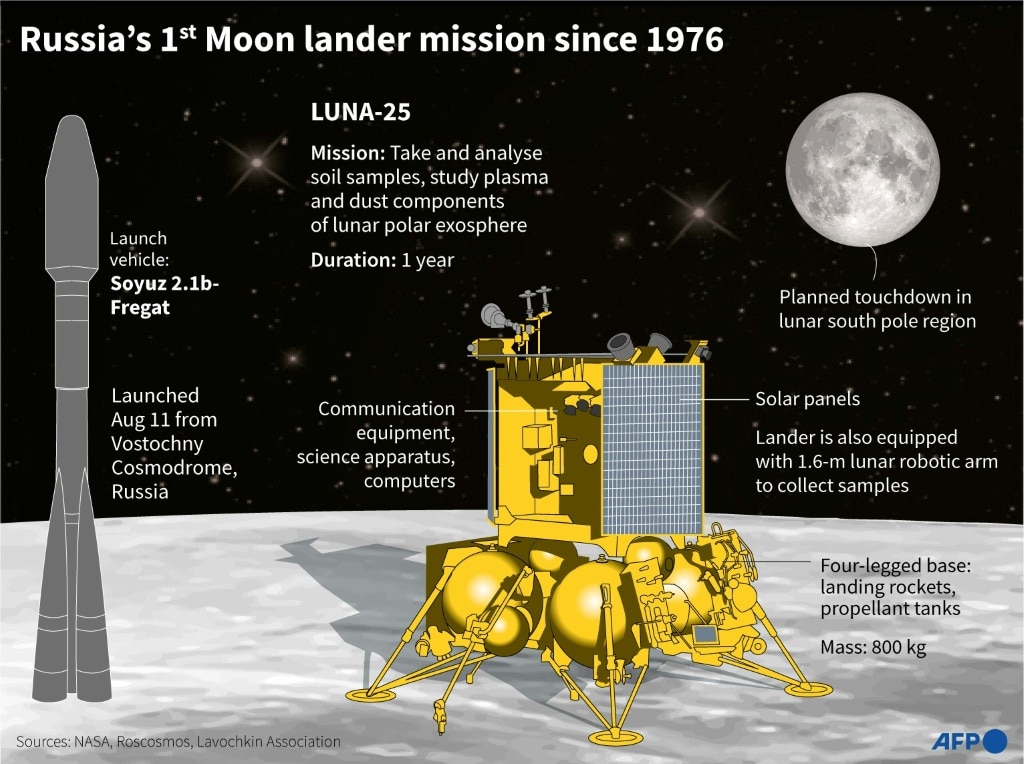

Russia had sought to become the first country to land a device on the lunar south pole. But on Sunday, Russian space agency officials said its Luna-25 vehicle crashed into the moon instead.

The Indian Space Research Organization, as India’s space agency is called, is expected on Wednesday to attempt to touch down a lander as part of its Chandrayaan-3 mission to a location in the south polar region. There, the agency intends to use a rover called Pragyan and carry out experiments.

The U.S. has its own plans to deploy landers to that area of the moon, partly through a NASA program that hires private companies to transport agency devices on landers the companies develop and have launched.

One of those companies, Houston-based Intuitive Machines, last week said that it reserved a six-day period starting Nov. 15 where SpaceX would blast off its Nova-C lander on a flight to the moon. The device would carry several NASA and commercial payloads.

Steve Altemus, Intuitive’s chief executive, said the company has worked to learn from failed landing attempts. “We are standing on the shoulders of everyone who’s tried and attempted and failed or succeeded,” he said.

Astrobotic Technology, a Pittsburgh-based space company also involved in NASA’s lander program, is planning to next year deliver an agency rover to the south pole, where it would measure lunar water resources. Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander is set to be launched to the moon toward the end of this year, though that craft wouldn’t seek to land on the south pole.

Russian space agency Roscosmos said Sunday’s failure came after the agency couldn’t get Luna-25 into its pre-landing orbit. Yury Borisov, the top leader at Roscosmos, said thrusters on the craft fired too long during the manoeuvre, leading to the crash, according to a report Monday from Russia’s state news agency TASS.

Tokyo-based ispace in April attempted to become the first private company to touch down a lander – aiming for the Atlas Crater, located in the moon’s northern hemisphere. But the lander encountered a problem with its altitude measurement, and eventually ran out of fuel, according to ispace, which believes the lander then crashed into the surface. The company has said it is making changes to its landing sequences for future missions.

Lunar landings are no easy feat, primarily because the moon’s thin atmosphere doesn’t hold enough air to slow a descending craft, the way parachutes have slowed spacecraft returning to Earth.

Instead, a lunar landing mission involves slowing down a spacecraft from thousands of miles an hour to a complete stop using engines that keep the craft from descending too fast as it is pulled in by the moon’s gravity. The fuel required to control that descent – and any necessary trajectory adjustments – is limited, Palotai said.

“You have to build a propulsion system that can carefully, with one-sixth the gravity, touch down softly,” said Dan Hendrickson, a vice president at Astrobotic. “It’s an enormously challenging task.” Japan and Russia aren’t the only countries that have struggled with recent moon landings. In 2019, Israel’s first privately-funded lunar mission ended in failure after the Beresheet spacecraft crashed into the moon following issues that made it impossible to slow the craft’s descent. Later that year, a rover from India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission – Chandrayaan-3’s predecessor – also hit the lunar surface after a problem with its braking thrusters.

China has successfully landed three uncrewed missions on the moon over the past decade. Most recently, the China National Space Administration’s Chang’e 5 carried a craft that landed on the lunar surface at the end of 2020. It scooped up samples, then deposited those into an ascender craft that took off from the surface and connected with an orbiting return vehicle, which flew back to Earth.

China plans further missions to the moon, including to the lunar south pole, and NASA officials have described the country’s growing space program as NASA’s main competition.

NASA also plans to have astronauts land near the lunar south pole as part of its multiyear exploration program, Artemis. Last year, the agency said it had identified 13 potential landing areas close to the region for its Artemis III mission.

This part of the moon is darker and colder than the sunlit side where the Apollo missions took place, making landings tougher. On the moon’s south pole, the sun casts shadows that can make it more difficult to distinguish surface features when attempting a landing.

The Artemis III mission, currently set for late 2025, would have astronauts touch down using a lander designed by SpaceX.

Dow Jones

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout