Coronavirus: The deadliest maze, how scientists tracked COVID-19 in secret

Deep in China, three men entered a cave and died with a mystery illness. Why was it kept under wraps for years?

In the monsoon season of August 2012 a small team of scientists travelled to southwest China to investigate a new and mysteriously lethal illness. After driving through terraced tea plantations, the scientists reached their destination: an abandoned copper mine, where — in white hazmat suits and respirator masks — they ventured into the darkness.

Instantly, they were struck by the stench. Overhead, bats roosted. Underfoot, rats and shrews scurried through thick layers of their droppings. It was a breeding ground for mutated microorganisms and pathogens deadly to human beings. There was a reason to take extra care. Weeks earlier, six men who had entered the mine had been struck down by an illness that caused an uncontrollable pneumonia. Three of them died.

Today, as deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic exceed half a million and economies totter, the bats’ repellent lair has taken on global significance.

Evidence seen by The Sunday Times suggests that a virus found in its depths — part of a faecal sample that was frozen and sent to a Chinese laboratory for analysis and storage — is the closest known match to the virus that causes COVID-19.

It came from one of the last droppings collected in the year-long quest, during which the six researchers sent hundreds of samples back to their home city of Wuhan. There, experts on bat viruses were trying to identify the source of the SARS — severe acute respiratory syndrome — pandemic 10 years earlier.

The virus was a huge discovery. It was a “new strain” of a SARS-type coronavirus that, surprisingly, received only a passing mention in an academic paper. The six sick men were not referred to at all.

What happened to the virus in the years between its discovery and the eruption of COVID-19? Why was its existence tucked away in obscure records, and its link to three deaths not mentioned? Nobody can deny the bravery of scientists who risked their lives harvesting the highly infectious virus. But did their courageous detective work lead inadvertently to a global disaster?

At the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming, doctors were confounded by a mystery illness. The six men who had been working in the bat-infested mine had raging fevers above 39C, coughs and aching limbs. All but one had severe difficulty in breathing.

After the first two men died, the remaining four underwent a barrage of tests for haemorrhagic fever, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis and influenza, but all came back negative. They were also tested for SARS, the outbreak that erupted in southern China in 2002, but also proved negative.

RELATED READING: Evidence points to Wuhan labs as source of infection | Scott Morrison does not buy into lab ‘conspiracy’ | Bats evolved as perfect virus carriers | How to prepare for a new pandemic

Mysterious new virus

The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), a renowned centre of coronavirus expertise, was called in to test the four survivors. These produced a remarkable finding: while none had tested positive for SARS, all four had antibodies against another, unknown SARS-like coronavirus.

Furthermore, two patients who recovered and went home showed greater levels of antibodies than two still in hospital, one of whom later died.

Researchers in China have been unable to find any news reports of this new SARS-like coronavirus and the three deaths. There appears to have been a media blackout. It is, however, possible to piece together what happened in the Kunming hospital from a master’s thesis by a young medic named Li Xu.

Li’s thesis was unable to say what exactly killed the three miners, but indicated the most likely cause was a SARS-like coronavirus from a bat. “This makes the research of the bats in the mine where the six miners worked and later suffered from severe pneumonia caused by unknown virus a significant research topic,” Li concluded. That research was already under way — led by the Wuhan virologist, Shi Zhengli, who became known as “Bat Woman” — and it adds to the mystery.

Coronaviruses are a group of pathogens that sometimes have the potential to leap species from animals to humans and appear to have a crown — or corona — of spikes when viewed under a microscope. Before COVID-19, six types of coronavirus were known to infect humans but mostly they caused mild respiratory symptoms such as the common cold.

The first outbreak of SARS — now known as Sars-Cov-1 to distinguish it from Sars-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 — is one of the deadly exceptions. It emerged in Guangdong, southern China, in November 2002 and infected 8096 people in 29 countries. It caused severe pneumonia in some and killed 774 people before petering out eight months later.

A race began to find out how a coronavirus had mutated into something so deadly and jumped from animals to humans. Shi and her team from the WIV began hunting among bat colonies in caves in southern China in 2004. In 2012 they were in the midst of a five-year research project when the call came to investigate the incident in the copper mine.

Out of the bat cave

Over the next year, the scientists took faecal samples from 276 bats. The samples were stored at minus-80C in a special solution and dispatched to the Wuhan institute, where molecular studies and analysis were conducted.

These showed that exactly half the bats carried coronaviruses and several were carrying more than one virus at a time, with the potential to cause a dangerous new mix of pathogens.

The results were reported in a scientific paper, “Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft”, co-authored by Shi and her fellow scientists in 2016.

Notably, the paper makes no mention of why the study had been carried out: the miners, their pneumonia and the deaths of three of them. The paper does state, however, that of the 152 genetic sequences of coronavirus found in the six species of bats in the mineshaft, two were of the type that had caused SARS.

One is classified as a “new strain” of SARS and labelled RaBtCoV/4991. It was found in a Rhinolophus affinis, commonly known as a horseshoe bat. The towering significance of RaBtCov/4991 would not be fully understood for seven years.

On December 31 last year, the Chinese authorities decided it was time to tell the world there was potentially a problem.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) was notified that a number of people had been struck down with pneumonia but the cause was not stated. On the same day, the Wuhan health authority put out a bland public statement reporting 27 cases of flu-like infection and urged people to seek medical attention if they fell ill. Neither statement indicated the new illness could be transmitted between humans or that the likely source was already known: a coronavirus.

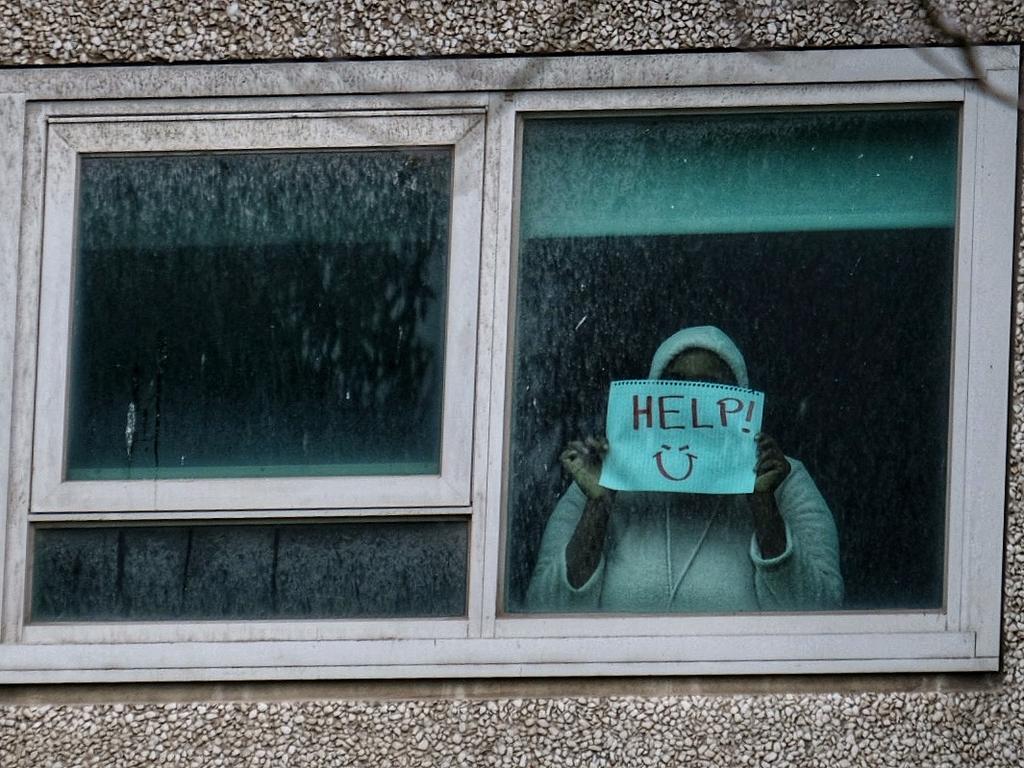

By the second week in January, desperate scenes were unfolding at Wuhan hospitals. Hopelessly ill-prepared and ill-equipped staff were forced to make life-and-death calls about who they could treat. Within a few days, the lack of beds, equipment and staff made the decisions for them.

Shi’s team managed to identify five cases of the coronavirus from samples taken from patients at Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital. The samples were sent to another lab, which completed the whole genomic sequence.

However, the sequence would not be passed to the WHO until January 12 and China would not admit there had been human-to-human transmission until January 20, despite sitting on evidence the virus had been passed to medics.

One of Shi’s other urgent tasks was to check through her laboratory’s records to see if any errors, particularly with disposal of hazardous materials, could have caused a leak from the premises.

She spoke of her relief to discover the sequences for the new virus were not an exact match with the samples her team had brought back from the bat caves. “That really took a load off my mind,” she told the Scientific American. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

She then set about writing a paper describing the new coronavirus to the world for the first time. Published in Nature on February 3 and entitled “A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin”, the document was groundbreaking.

It set out a full genomic description of the COVID-19 virus and revealed that the WIV had in storage the closest known relative of the virus, which it had taken from a bat. The sample was named RaTG13. According to the paper, it is a 96.2 per cent match to the COVID-19 virus and they share a common lineage distinct from other SARS-type coronaviruses. The paper concludes this close likeness “provides evidence” that COVID-19 “may have originated in bats”. In other words, RaTG13 was the biggest lead available as to the origin of COVID-19. It was therefore surprising that the paper gave only scant detail about the history of the virus sample, stating merely that it was taken from a Rhinolophus affinis bat in Yunnan province in 2013, hence the “Ra” and the 13.

Inquiries have established, however, that RaTG13 is almost certainly the coronavirus discovered in the abandoned mine in 2013, which had been named RaBtCoV/4991 in the institute’s earlier scientific paper. For some reason, Shi and her team appear to have renamed it.

The clearest evidence is in a database of bat viruses published by the Chinese Academy of Sciences — the parent body of the WIV — which lists RaTG13 and the mine sample as the same entity. It says it was discovered on July 24, 2013, as part of a collection of coronaviruses that were described in the 2016 paper on the abandoned mine.

Covid’s close cousin

In fact, researchers in India and Austria have compared the partial genome of the mine sample that was published in the 2016 paper and found it is a 100 per cent match with the same sequence for RaTG13. The same partial sequence for the mine sample is a 98.7 per cent match with the COVID-19 virus.

Peter Daszak, a close collaborator with the Wuhan institute, who has worked with Shi’s team hunting down viruses for 15 years, has confirmed to The Sunday Times that RaTG13 was the sample found in the mine. He said there was no significance in the renaming, due to changes in the coding system. He recalled: “It was just one of the 16,000 bats we sampled. It was a faecal sample, we put it in a tube, put it in liquid nitrogen, took it back to the lab. We sequenced a short fragment.”

In 2013 the Wuhan team had run the sample through a polymerase chain reaction process to amplify the amount of genetic material so it could be studied, Daszak said. But it did no more work on it until the COVID-19 outbreak because it had not been a close match to SARS.

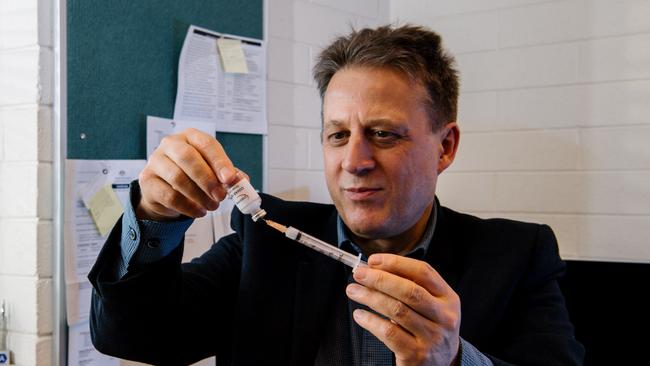

Other scientists find the initial indifference about a new strain of the coronavirus hard to understand. Nikolai Petrovsky, professor of medicine at Flinders University in Adelaide, said it was “simply not credible” that the WIV would have failed to carry out any further analysis on RaBtCoV/4991, especially as it had been linked to the deaths of three miners. “If you really thought you had a novel virus that had caused an outbreak that killed humans, there is nothing you wouldn’t do — given that was their whole reason for being [there] — to get to the bottom of that, even if that meant exhausting the sample and then going back to get more,” he said.

In recent weeks, academics are said to have written to Nature asking for the WIV to write an erratum clarifying the sample’s provenance, but the Chinese lab has maintained a stony silence.

The origin of COVID-19 is one of the most pressing questions facing humanity. Scientists worldwide are trying to understand how it evolved, which could help stop such a crisis happening again.

The suggestion that well-intentioned scientists may have introduced COVID-19 to their own city is vehemently denied by the WIV, and its work on the origin of the virus has become an X-rated topic in China. Its leadership has taken strict control of new studies and information about where the virus may have come from.

The investigation

Over the next few days, WHO scientists will be allowed to fly into China to begin an investigation into the origins of the virus after two months of negotiations.

Many experts, such as Daszak, believe the source of the virus will be found in a bat in the south of China. “It didn’t emerge in the market, it emerged somewhere else,” said Daszak. He said the “best guess right now” is that the virus started within a “cluster” on the Chinese border that includes the area where RaTG13 was found and an area just south of the mineshaft, where another bat pathogen with a 93 per cent likeness to COVID-19 was discovered recently.

As for how the virus travelled to Wuhan, Daszak said: “Fair assumption is that it spilt into animals in southern China and was then shipped in, via infected people, or animals associated with trade, to Wuhan.”

The final, trickiest question for WHO inspectors is whether the virus might have escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan.

Is it possible, for example, RaTG13 or a similar virus turned into COVID-19 and leaked into the population after infecting one of the scientists at the Wuhan institute?

This seriously divides the experts. Australian virologist Edward Holmes has estimated that RaTG13 would take up to 50 years to evolve the extra 4 per cent that would make it a 100 per cent match with the COVID-19 virus. Martin Hibberd, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, believes it might take less than 20 years to morph naturally into the virus driving the current pandemic.

But others say such arguments are based on the assumption the virus develops at a constant rate. “That is not a valid assumption,” said Richard Ebright of Rutgers University’s Waksman Institute of Microbiology. “When a virus changes hosts and adapts to a new host, the rate of evolutionary change is much higher. And so it is possible that RaTG13, particularly if it entered humans prior to November 2019, may have undergone adaptation in humans at a rate that would allow it to give rise to Sars-Cov-2. I think that is a distinct possibility.”

Ebright believes an even more controversial theory should not be ruled out. “It also, of course, is a distinct possibility that work done in the laboratory on RaTG13 may have resulted in artificial in-laboratory adaptation that erased those three to five decades of evolutionary distance.”

It is a view Hibberd does not believe is possible. “Sars-Cov-2 and RaTG13 are not the same virus and I don’t think you can easily manipulate one into the other. It seems exceptionally difficult.”

Ebright alleges, however, that the type of work required to create COVID-19 from RaTG13 was “identical” to work the laboratory had done in the past. “The very same techniques, the very same experimental strategies using RaTG13 as the starting point, would yield a virus essentially identical to Sars-Cov-2.”

The Sunday Times put a series of questions to the WIV, including why it had failed for months to acknowledge the closest match to the COVID-19 virus was found in a mine where people had died from a coronavirus-like illness. The questions were met with silence.

THE SUNDAY TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout